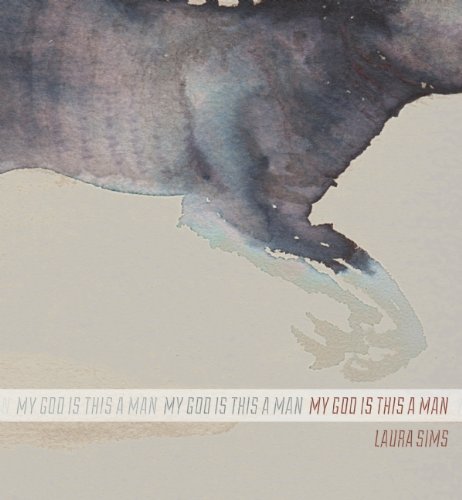

My god is this a man

Laura Sims

88 pages, paperback

ISBN 978-1934200735

Fence Books, 2014

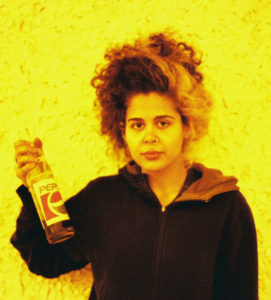

Review by Lara Mimosa Montes

My god is this a man by Laura Sims treads sacred ground; like Mallarmé’s staggering Symbolist feat Un coup de dés, it is a formally haunting and enigmatic work. A delicate composition written around the edges of confessions made by both convicted and suspected killers—from Kip Kinkel to The Chicago Rippers—My god exposes the abysses in language, the dreaded “IF” inside every speech act. Spoken as if from the thrown voice of one lost in either the viscerally chaotic present or the unknowable afterlife, the poet writes, “I stood//like a rag from which the soul//escaped.” From this shattered landscape emerges “a feast/made of beautiful feelings.”

Like so many other bewildered Americans, the poet is but one among “the hordes/of the curious.” Who was Richard Trenton Chase? What makes an Ed Gein? Disinterested in theories of sociopathy or biopsies of the serial killer brain, Sims refuses to indulge in forensic facts or straightforward moralizing proclamations. Instead, her small poems make do with inconclusive truths:

I don’t

I don’t deny (I wasn’t there) but

I’d had the dearest little dream

Staying true to the style of her previous books, Stranger (2009) and Practice, Restraint (2005), Sims excels in reporting only the essential. The poet is not a stenographer, nor is she a witness or a judge. Like Emily Dickinson, she is a woman looking out a window, and a writer capable of rare and exacting insight: “See the pines/that are//”such as they are”/and the ones that escaped.” These lines, which are framed by a square, lie opposite a page featuring no text, but only a larger, Malevich-like black square. The black boxes forecast the poet’s disquiet, but beyond that, what kind of condemnation, doubt, or profound thought behind them exists? In My god, the reader’s gaze is always oriented elsewhere as the poet reconciles herself with “The Nothing/Like Thought” in “That heavenly/structure—the world.”

Although Sims’s squares may initially seem intrusive, or out of place, they—like the censored scenes of certain unfathomable acts—just cut to black, rather than fade out. By refusing to reproduce the most gratuitous scenes of violence, the poet is also, with these confrontational boxes, refusing her readers’ scopophilic need for evidence. In addition, some of these squares are filled with text: a mixture of language from Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s bedside confession and Sims’s own “Bedtime Relaxation” meditation. One line reads, “Let the long bones settle down into the bed.” The strangeness of these squares accrues alongside Sims’s stark meditative commands; as a result, the accompanying texts read like eerie missives from the damned or dead.

Sims’s ability to work within these grief and guilt-ridden registers is even more striking when considered alongside projects like Maggie Nelson’s Jane: A Murder, Julie Carr’s 100 Notes on Violence, and Kristin Prevallet’s I,Afterlife: An Essay in Mourning Time. Furthermore, the title of Sims’s book suggests her poetry’s place among these feminist interrogations against culturally-sanctioned forms of violence. Sims’s contribution to this canon are the voices of those denounced as guilty and beyond redemption or rehabilitation, like Bill Heirens, also known as “The Lipstick Killer,” who said, “In plain words I think I am a worm.” Sims takes Heirens’s words and repeats them back to us, stunned by their uncanny inadequacies: “I think/Words//I think/Worm.” The poet’s re-writing of Heirens—indicative perhaps of her own disgust and contempt for the subject of her project—is reminiscent of Gertrude Stein and her experiments in repetition. Somewhat counter-intuitively, however, one is also reminded of Adrienne Rich, who, writing of herself in “Twenty-One Love Poems,” asks, “What kind of beast would turn its life into words?/What atonement is this all about?”

Sims’s poems go to a dark place in their attempts to speak about the unspeakable. A perceptive philosophical meditation on guilt and ethical responsibility, My god is this a man offers us more than its fair share of dolesome propositions. Rather than defer to a set of over-determined details and media-driven sensationalisms, these poems give, in their withholding, and they do so with astonishing grace.

Lara Mimosa Montes is a PhD candidate in English at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her poems have recently been published in Triple Canopy, DIAGRAM, and Revolver, and her reviews have appeared in BOMB, Puerto del Sol, Transgender Studies Quarterly, The Lit Pub, and Bookslut. She currently teaches at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

Lara Mimosa Montes is a PhD candidate in English at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Her poems have recently been published in Triple Canopy, DIAGRAM, and Revolver, and her reviews have appeared in BOMB, Puerto del Sol, Transgender Studies Quarterly, The Lit Pub, and Bookslut. She currently teaches at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.