In my undergraduate poetry workshop this semester, one of my students recently submitted a poem called “Fake News.” It began with a simple three-word line: “What is Real?” The question is banal, to be sure, on the level of the sentence; yet it is a very important one to ask in terms of aesthetics, philosophy, and politics. In a certain way, it is the question. In his manifesto Reality Hunger (2010), David Shields has argued, “Every artistic movement from the beginning of time is an attempt to figure out a way to smuggle more of what the artist thinks is reality into the work of art.” As in aesthetics, so in politics: politicians are very much in the business of smuggling their versions of the real into their rhetoric, policies, and legislation. If, as Percy Bysshe Shelley famously argued, “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” then politicians are the unacknowledged artists, if not con artists. Here’s some reality: “Criminal aliens and gang members have used our weak borders to gain entry into our country.” Here’s some more: “Violent smugglers are exploiting our laws and porous borders for their own gain.” These statements come from a “fact sheet” from www.whitehouse.gov, which explains why President Donald J. Trump has recently declared a national emergency at the southern border. There is certainly a lot of smuggling going on—in artist studios, in writers’ colonies, and in the White House.

These days I’ve been mostly reading poets who, to quote Shields, have been “breaking larger and larger chunks of ‘reality’ into their work” as I am finishing up a book tentatively entitled “Extending the Document in Contemporary North American Poetry” (forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press.) I have to admit that I’ve smuggled very tiny chunks of that manuscript draft—as well as other manuscripts—into this reading list though the rhetorical situations of these various writings are all different. My book studies contemporary poems that prominently include found documents and interpolated texts. What are documents, after all, but “chunks” of textual reality? Documents, of course, can be both banal and important. They bore us; but they also perform actions (“NOW, THEREFORE, I, DONALD J. TRUMP, by the authority vested in me […] hereby declare that a national emergency exists at the southern border of the United States”) and compel people to take action. Documents languish in archives, forgotten and unread, receding into what George Oppen called, in his clever play on Shelley, the “unacknowledged world.” Perhaps most importantly, documents fix inscriptions into place so that we can call renewed attention to them, so that we can argue with them and build upon them—crucial activities, I think, in this age of fake news.

Poetry can’t be “news that stays news,” as Ezra Pound said, if we don’t read it in the first place, if we don’t keep it alive in our memories.

WHEREAS BY LAYLI LONG SOLDIER

(GRAYWOLF PRESS, 2017)

The title poem, which occupies the entire second section of this formidable book, is a sequence that close reads and riffs on “S.J.Res.14” from the 111th Congress (2009-2010), which is “a joint resolution to acknowledge a long history of official depredations and ill-conceived policies by the Federal Government regarding Indian tribes and offer an apology to all Native Peoples on behalf of the United States” (111th Congress (2009-2010)). As Long Soldier notes, though President Barack Obama signed the resolution in 2009, “No tribal leaders or official representatives were invited to witness and receive the Apology on behalf of tribal nations” and the “Apology was then folded into a larger, unrelated piece of legislation called the 2010 Defense Appropriation Act.” Call it, following Pound, legislation “containing” (a tendentious) history. As an extended exegesis of this congressional document, Whereas combines lyric prose poetry reflecting lived and affect-laden experience with a critique of the apology’s hedging and self-serving rhetoric. Long Soldier, for example, says, “WHEREAS I tire. Of my effort to match the effort of the statement: ‘Whereas Native Peoples and non-Native settlers engaged in numerous armed conflicts in which unfortunately, both took innocent lives, including those of women and children.’” Trump, of course, is well versed in perniciously smuggling violent Eurocentrism into American identity, having notoriously described the 2017 clash between white nationalists and counter-protestors in Charlottesville as having “very fine people, on both sides.” Long Soldier tends to use the full space of the page in all sorts of innovative ways, making this a compelling book to read, look at, and scrutinize. Whereas is coming up on one of my syllabi and I welcome the chance to re-read it.

KITH BY DIVYA VICTOR

(FENCE, 2017)

At just over 200-pages, Kith is, so to speak, a collection of many “kindred” mini-books under the sign of transgenerational, transcultural, transhistorical, and translingual “knownness” (kith, coming from the Old English cýððu). It combines oral legend, prose poems, list poems, visual poems, creatively annotated photographs sourced from family albums, quotations, and ritualistic verses and diagrams. It juxtaposes memoir, lyric art-historical essay, and image-text collage in a post-colonial key. Its chunks of reality include an image of a 1778 painting by John Singleton Copley called Watson and the Shark, a facsimile page of the 1848 Phrase Book: Or, Idiomatic Expressions in English and Tamil (Designed to assist Tamil Youths in the Study of the English Language), and an excerpt from a 2016 Reuters report that describes how police officer Eric Parker body slammed the 57-year-old grandfather Sureshbhai Patel to the ground in Huntsville, Alabama, an unprovoked act of violence that left Patel, who was visiting his son from India, “partially paralyzed.” Kith truly contains “multitudes,” as Walt Whitman might say, a suggestion that America needs a new Leaves of Grass for the twenty-first century. In fact, Kith ends with a send-up of Whitman’s “Passage to India” with Victor emerging victorious. I can imagine a future version of Kith in, say, 2040, that represents a deliberate and incremental expansion of this 2017 edition: if I’m still around by then, I would read that too.

VOYAGE OF THE SABLE VENUS AND OTHER POEMS

BY ROBIN COSTE LEWIS

(KNOPF, 2015)

The title piece “Voyage of the Sable Venus” is part-procedural long poem and part-conceptual ekphrasis that is, according to Lewis, “comprised solely and entirely of the titles, catalog entries, or exhibit descriptions of Western art objects in which a black female figure is present, dating from 38,000 BCE to the present.” Lewis, in other words, counter-intuitively lavishes her attention not on the ergon, the work, but the work’s supplement, what Jacques Derrida might call the parergon. She reframes the parergonal documentation into a masterpiece of research-based poetry so as to bring what has been marginalized to the center. Lewis is particularly adept at leveraging puns, fragments, and strategic enjambments: “I Sis Aphro / Dite clasping a garment // rolled about her hips: / The Place of Silence.” In an essay on her poem’s composition “Broken, Defaced, Unseen: The Hidden Black Female Figures of Western Art,” Lewis says, “I became a very accomplished international art thief. It was easy. By writing down the titles only, I was able to steal all of the art by leaving it there. […] I’d write down the title in my notebook, bring her aboard, wrap her in blankets, clothe and feed her. By the end, the ship was full.” In an act of counter-smuggling, Lewis shows us the unacknowledged realities of art historical representation in the West.

LOOK BY SOLMAZ SHARIF

(GRAYWOLF PRESS, 2016)

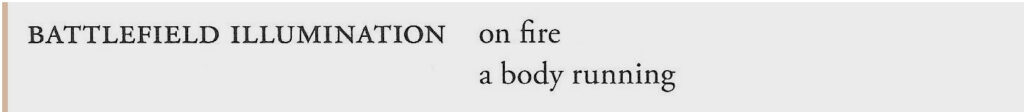

Sharif’s provocative volume appropriates language from “the United States Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms as amended through October 17, 2007,” creating a potent mixture of poetic and military discourses. “Battlefield Illumination,” which begins the book’s second section, provides a dramatic example of such interdiscursive mixture:

In what I might call a post-Imagist poem of war, Sharif ironizes the DOD’s specialized jargon, which, like any bureaucratized language, often abstracts one completely from conditions on the ground. For example, I took a quick spin through the February 2017 edition of the DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms and found phrases such as “Adaptive Planning and Execution system,” “coordinated fire line,” “full-spectrum superiority,” and “munitions effectiveness assessment.” In contrast, Sharif’s “Battlefield Illumination” illuminates by reminding us of the brutally traumatized bodies that are the casualties of war. I’m in the middle of teaching this book right now in my graduate course and Sharif has my students at full attention.

LOOK BY SOLMAZ SHARIF

(GRAYWOLF PRESS, 2016)

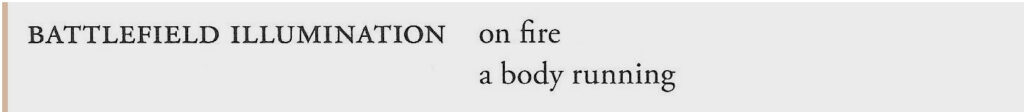

Sharif’s provocative volume appropriates language from “the United States Department of Defense’s Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms as amended through October 17, 2007,” creating a potent mixture of poetic and military discourses. “Battlefield Illumination,” which begins the book’s second section, provides a dramatic example of such interdiscursive mixture:

In what I might call a post-Imagist poem of war, Sharif ironizes the DOD’s specialized jargon, which, like any bureaucratized language, often abstracts one completely from conditions on the ground. For example, I took a quick spin through the February 2017 edition of the DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms and found phrases such as “Adaptive Planning and Execution system,” “coordinated fire line,” “full-spectrum superiority,” and “munitions effectiveness assessment.” In contrast, Sharif’s “Battlefield Illumination” illuminates by reminding us of the brutally traumatized bodies that are the casualties of war. I’m in the middle of teaching this book right now in my graduate course and Sharif has my students at full attention.

DRIFT BY CAROLINE BERGVALL

(NIGHTBOAT BOOKS, 2014)

Drift aggressively blends a variety of genres and media just as it provocatively juxtaposes texts about medieval sea voyages in Northern Europe with one of the many catastrophes of the ongoing Mediterranean Migrant Crisis. Beginning with a series of line drawings, the first line of text in Drift is “Let me speak my true journeys own true songs,” which is a translation from the Anglo-Saxon poem The Seafarer. This section, appropriately called “Seafarer,” also includes borrowings from the Icelandic Vinland Sagas and Finnboga Saga. The book’s traumatic core—which is printed, funereally, on black pages—is an excerpt from the Report on the “Left-To-Die Boat” by Forensic Oceanography about the rubber dinghy that languished between Libya and Lampedusa during two harrowing weeks in 2011 despite the fact that it was extensively surveilled by NATO ships and helicopters. Most of the 72 African migrants on board perished from thirst and starvation. The central juxtaposition of Bergvall’s book creates a nonsynchronous space, in which we can read canonical saga through contemporary tragedy and vice versa. Bergvall’s section “Report” quotes survivor Dan Haile Gebre: the sea was very dark with too much waves and wind. We lost our direction. From then on and for several days we don’t know anything. It is upsetting that this testimony could have been lifted from the 10th century Finnboga Saga, which contains phrases such as the fair wind failed and they wholly lost their reckoning. We think—perhaps not incorrectly—that modernity has brought us so much progress, technological or otherwise. We build ships and helicopters; we illuminate battlefields; and we have the capacity to erect “big, beautiful wall[s].” But how much progress have we really made? If I could add a sixth book to this list, it would be Dialectic of Enlightenment by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. And if I could decidedly not recommend a book it would be Steven Pinker’s newly released Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. The poems that I’m reading make different cases, and they make them through different means.