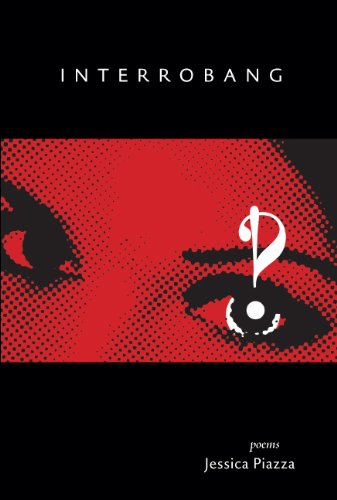

Interrobang

Jessica Piazza

ISBN-13: 978-1597097222

72 pages, paperback

Red Hen Press, 2013

$17.95

Review by Fox Frazier-Foley

Jessica Piazza’s lovely first book of poems, Interrobang, is a formal and metaphysical engagement with questions of what can and cannot be contained. Titled after a piece of punctuation that signifies both exclamation and interrogation, the book is unsurprisingly obsessed with dualities: its sonnets follow an almost binary pattern as they vacillate between pathological extremes of love and fear. Each poem is titled after a clinical phobia or philia, and accordingly celebrates and/or laments the implied emotional parameters of such terrors.

Interrobang begins with fear—of music (as the product of another person’s consciousness), of weakness (as the inability of the self to meet the demands of an external stimulus or challenge) and of natural disasters, which invade and destroy private, interior landscapes with the elements, wreaking havoc by violently bringing the unwelcome outside in. In fact, the book is preoccupied with a foundational outside/inside dichotomy: what is outside of the speaker’s own identity, or the spaces that ensconce her, are by nature a threat, as in Melophobia:

They’ll tell you there are only two ways: flawed

windpipes that knock like water mains

behind thin walls or else a lovely sound like wood-

winds sanded smooth—no middle ground. They’ll find

you practicing your scales, determined not

to fail. A voice too frail, too thin, beginagain, again, again, now overwrought,

now under-sung; not done. They recommend:just sound as much yourself as possible.

But we know possible is slippery.

Melophobia‘s uncomfortably spotlit speaker, rendered incapable of even sounding like herself, is advised to “Sing into a conch and you’ll sound like yourself./ Sing into a conch and you’ll sound like the sea.” This corresponds with a description, just a few lines earlier, to “[her] New York” as “an ocean made of steel”. The ultimate restoration of vocal/sonic identity, in other words, is directly related to the return of a space one identifies as one’s own, a location that is an extension of oneself, and does not threaten to dilute identity. Similarly, in Lilapsophobia and its “preparedness: a myth,” home is described as “undone beneath the raised hand of the bay.”It is not floodwaters alone that drive the speaker from her comfort zone, however, but also a tempestuous lover, to whose “cyclonic” nature these natural disasters cannot compare:

. . . No way

to gauge you: wrath or pleasure, unfixed track

away or toward. Untoward, you leave no wake

She says, and her inability to prepare for the dangers of volatile interpersonal encounters becomes more palpable than the waters from which she flees.

It is not until Clithrophilia that a discussion of love is introduced into the text—specifically, a love of being enclosed. “I’ve ached for it all: a closet; a stall;/ a crevice between your flesh and the wall,” the speaker declares, again addressing her lover, whom she identifies as the antidote to “freedom I’ve heeded too often.” He is finally christened as both her “darkness” and her “coffin.”

—

The significance of these closing images is augmented by Achluophilia, in which an obsessive love of darkness provides necessary psychic relief: “One should be blind when/ sleeping; waking’s already/ hardship, overload of the heart.” This series of poems revolve around forces that promise to preserve the boundaries of an individual consciousness. Being enclosed emphasizes the borders set by the body between self and other, while darkness gives us a cover for actions and appearances we might wish to hide from others, thereby allowing us extra agency over our external identities.

It becomes very clear that, as far as the Sartresian parameters of this speaker’s reality are concerned, “outside” is trouble. That which is outside us—such as foreign languages, as examined in Xenoglossophobia—problematize our certainties and challenge our definitions.

It would be possible, at this point, for the poems to fall into a game-like binary pattern, in which the rest of the philias and phobias listed fall into one category or another. However, Piazza foresees this and vaults past it with Phobophilia, a poem about the pathological love of fear. If we love the comfort of the familiar but fear the challenge of the foreign, what happens to those binaries when we conflate love and fear? A gesture towards the answer seems present in the poem Caligynephilia, in which the speaker is simultaneously the beautiful woman who inspires fear and the empowered, violent, self-described “ugly girl” who—despite her sense of hard-earned agency—still fears the consequence of being reduced to a pretty/desirable object:

Those nights when hand-

some boys unstick

and exit, quick,

I wake her up

still in my clutch,

enraged. Then: punch.

Eisoptrophilia and Eisoptrophobia are poems about, respectively, pathological love and pathological fear of mirrors. By long convention, literary mirrors reflect both physical and meta-physical attributes. Eisoptrophilia represents the never-quite-complete representation of a constantly evolving self as a freeing, uplifting experience, in which the nuances of the speaker’s reflected visage absorb her like a lake:

Just below clear water, I reside

as duplication of the lake. Take me

away, another underneath again.

What mirrors cannot ditto isn’t sin.

Eisoptrophobia, on the other hand, treats this same experience as an exercise in failure and futility:

Those fleeting squares reveal our darkness back.

Aloof, the rain plays taps. Above, the trees

are inimitable. Distinct, thus blessed.

Reflected, I am never at my best.

As the book draws to a close, what to make of all these overlapping contradictions and inconsistencies that have been revealed—these useful failures? Piazza answers this, perhaps, in Khakorrhaphiophobia, which speaks to the pathological fear of failure:

A doppelgänger born with every task:

The evil twin of its unfinishing.

The harbor, never there, is menacing.

Its ebb, unanswered question asked and asked.

In this extreme universe, as in ours, failure is a necessity, but an uncomfortable one. The only way to embrace it, from an irrational or phobic standpoint, might be to simply admit defeat. It is from these threads of despair that Piazza weaves the collection’s final poem, What I Hold, a hymn to the finite, incomplete mistakes of human experience which, mosaic-like, allow us to access the tiny pieces of truth we need to harvest a greater, future truth. As the poem reaches its conclusion, we see how a past mistake of the speaker’s (a failure to express human kindness towards an elderly woman in need of help) continues to haunt her. The negativity associated with this regrettable action is palpable. Yet Piazza’s speaker finds a way to resist her own moral judgment. Her salvation, and ours, stems from the incompleness of this story, the ability to take that sense of Keatsian negative capability and project it into the future:

I knew this damage was my own.

I had been taught such fears. I knew. And so?

Perhaps I changed my mind and drove her home.

And maybe to this day that choice still seems

like a hint, a minute’s inkling of what gleams.

And, like the sparkling meter and surprising language of these poems, gleam it does.

Fox Frazier-Foley is a Vodou initiate who hails from upstate New York and northern Virginia. Her poetry chapbook, Exodus in X Minor, was selected by Beth Couture as winner of the Sundress Publications Chapbook Competition, and her first full-length poetry collection, The Hydromantic Histories, was chosen by Chard deNiord as winner of the Bright Hill Press Poetry Book Prize. She is Editor-Curator of TheThe Infoxicated Corner at TheThe Poetry Blog, and a creator and Managing Editor of the small, Los Angeles-based press Ricochet Editions. She writes poetry horoscopes for Luna Luna Magazine.

Fox Frazier-Foley is a Vodou initiate who hails from upstate New York and northern Virginia. Her poetry chapbook, Exodus in X Minor, was selected by Beth Couture as winner of the Sundress Publications Chapbook Competition, and her first full-length poetry collection, The Hydromantic Histories, was chosen by Chard deNiord as winner of the Bright Hill Press Poetry Book Prize. She is Editor-Curator of TheThe Infoxicated Corner at TheThe Poetry Blog, and a creator and Managing Editor of the small, Los Angeles-based press Ricochet Editions. She writes poetry horoscopes for Luna Luna Magazine.