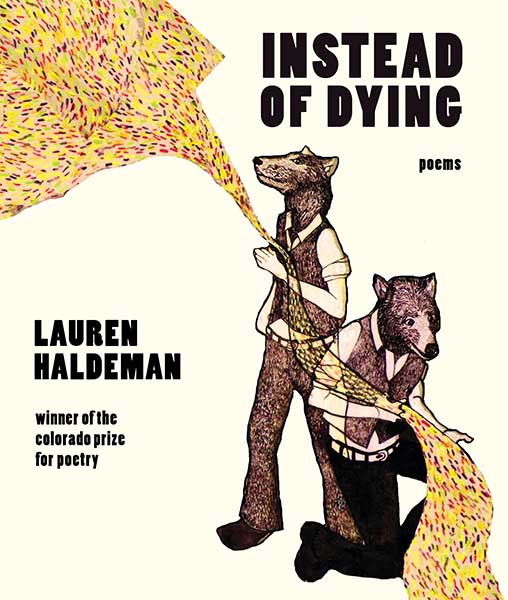

Instead of Dying

Lauren Haldeman

University Press of Colorado, 2017

Paperback & Ebook, 86 pages

$16.95|$13.95

Review by Abigail Zimmer

“I miss you already / I miss future-you,” writes Lauren Haldeman in her first book, Calenday, a book that celebrates the strange and often alien-like gift of new motherhood—and a book that begins to process the sudden and inexplicable death of her brother. “How do I get started on this?” she asks in the same poem about her brother. “Or am I already in the middle of / this?”

I was drawn to Calenday because of my own grief in losing someone I loved too young and too inexplicably, and I was grateful for the way Haldeman put down on paper the turmoil and confusion that follows. Grief does not go away, but it does evolve, often into forms that enable us to get through the day. Haldeman’s second book of poems, Instead of Dying, reveals a different phase of her journey, another “middle,” this time exploring the many possible “future-yous” of her brother that she so misses.

Instead of Dying expresses the speaker’s grief through form. The book starts and ends with a series of prose poems beginning with the phrase “instead of dying” that imagines what could have happened next in her brother’s life. In the second and fifth sections are pairs of twenty-line poems, each line a mirror of its counterpart on the opposite page. Perhaps the most powerful form in the book, the mirrored lines sometimes say the same thing in a different way, an echo; at other times, the meaning entirely changes, though using similar words.

“Because I didn’t

know which way was up, you

became up, you seemed

to embody up. Moving up towards

what I thought was you. Never

has an object been so much

like a fist of thrones.”

and

“You were the only one who knew.Suddenly you becametwo words: un-moving / un-embodied. OrNever-you. Or Was-thought. What I

must have been objecting tofirst, and fast.”

To read these poems together is to be immersed in the strange fog of grief—complete with circular reasoning, the task of processing a world which has suddenly become absurd. Language fails, and so a structure provides the scaffolding to say what is needed. Inverted syntax allows for new reasoning, a new thinking to inhabit a world that’s been rewritten.

At the heart of the book is a gathering of scientists (a discovery of scientists?) —Galileo, Newton, Copernicus— all figuring out how the earth moves, what and where is the center, how we can predict future behavior. Haldeman has the mind of a scientist as well as a poet, with a curiosity about the natural world also present in her first book. “I feel / what? / The hug of the world / gigantic swirling vortex of invisible matter / NATURE & nature’s laws / lit up with watching.” These are her strengths: writing with wonder, with play, with honesty—even through suffering. As such, I can’t help but revel and delight in her poems, to feel hopeful despite the underlying grief.

“I loved a spider this May, I

loved a dog as much as

my relations, recognizing, didn’t I,

that the requirements I visually

love are face-based, dog-based.

Isn’t the spider’s face my face?”

The end of a book is not the end of mourning, and I appreciate how Haldeman allows her journey to continue into her second collection (although perhaps “allow” is the wrong word; it’s usually compulsion that drives us to the page). In my own journey, I’ve been afraid that people will grow tired of hearing about the same painful memories, and yet I’m not done processing them. I think of the writer Maggie Nelson, who explores the family tragedy of her young aunt’s murder in the long poem Jane: A Murder and then again in documentary essays about the court’s proceeding in her follow-up book The Red Parts. There is value to the larger body of a writer’s work that shows the journey is not simple nor neatly wrapped up nor one book long.

“Each of these stories placed inside another story, making an infinite mirror of stories, making the actual story, the story we don’t want, seem a little less real,” writes Haldeman.

A little less real. The contemporary scholar Gerald Bruns wrote, “Poetry is a sort of world-making,” a quote I’ve always loved for how poetry can delve into fantastical realms the way that fiction does—talking animals, a mysterious guide in mysterious woods, the potential for fairy-tale transformations. But it also means making a world in which we can bear to live.

Haldeman makes this world in presenting all the possibilities of a life, an alternate reality in which one can still respond to and interact with this life. “I must become the person imagining you dually,” she writes, and in both scenarios that follow, her brother is alive.

Haldeman succeeds. As a reader who never knew this friend/brother/son/multi-faceted person, my view of him is larger than life. Through Haldeman’s poems, I see him as a marine biologist, beneath a willow tree, bearing maple sugar treats, adopting all the cats, making grilled cheese, in Kentucky, in Quebec, in Sault Ste. Marie, in April. I see him in so many living settings. I see him “with infinite illumination.”