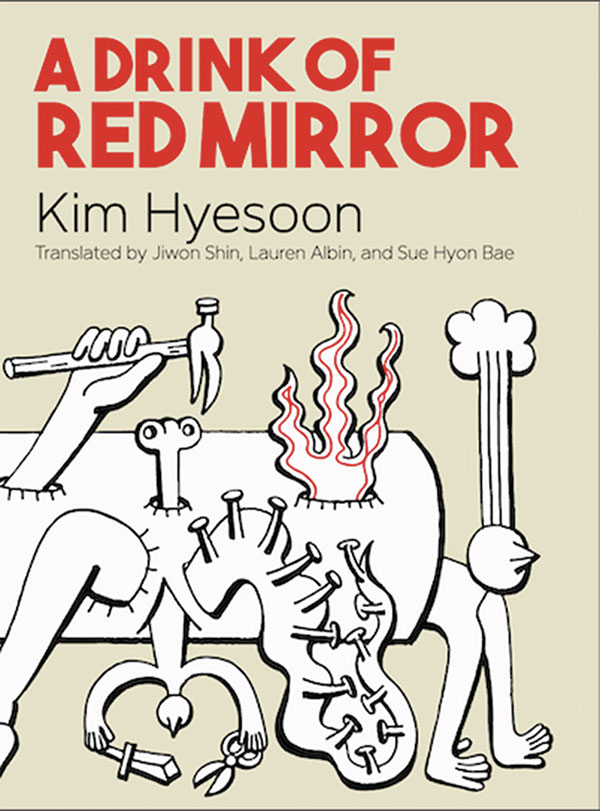

Kim Hyesoon

A Drink of Red Mirror

Translated by Jiwon Shin, Lauren Albin, and Sue Hyon Bae

Action Books, 2019

Paperback, 96 pages

Review by Ryan Bollenbach

The poems in Kim Hyesoon’s A Drink of Red Mirror collapse the temporally, spatially, and existentially discrete into each other in daring turn after daring turn. In Kim’s hands, the collapses recurring in the poems in this volume offer ecstatic and sensational possibilities. From the very first poem, “Poet’s Preface,” Kim lays the tear-away foundation for these future collapses:

Like walking the streets in a heatwave

with a block of ice wrapped in a blanket

I shivered away these hours. Like shoes getting soaked

with every footstep

with every stream of cold blood. (3).

The speaker is shivering in a heat wave, trapped between cold and heat, ice and water. Kim’s penchant for surprising anthropomorphism leads me to imagine the ice “shivering away” with the speaker. The speaker’s blood (made cold by the melting ice?) soaks her shoes. Sensorial and physical slippages compound. The lack of a referent in the final simile creates a suggestive ambience, modifying the poem’s environment for hidden purposes. In the two short sentences of this poem, Kim collapses time, space, states of being, and temperature. Characteristically, she isn’t even bothered to give us an occasion for the speaker’s heatwalk.

So a reader might ask what kind of “I” walks shivering and bloody in a heatwave? Opens its eyes inside your blood? Boils herself out of herself? Worries about the cows inside the self while drinking a glass of a milk? Glosses over the blood freezing on her thighs? What kind of poet is so entranced by the “I” that she never defines it?

In this collection, Kim’s various speakers haunt and are haunted, possess and are possessed, by a myriad of things from butterflies to sadness to conversations inside a Baskin Robbins to Seoul itself. Who the speaker is might be beside the point. The speakers flinch in out and of identities so rapidly it becomes a dizzying experience itself, a transcendental teacup ride.

In “A Bouquet of Red Roses,” a fifteen-line epic love poem, the speaker flits inside the second person “you” at the atomic level. She opens her eyes inside “you,” then her dry eyeballs open “inside a bouquet of red roses under your skin.” Then, in the poem’s rapturous peak, the speaker resolves to “rupture the red blood cells of time.” Then, doomed to eternity on a Mobius strip “outside me inside you forever,” concludes exclaiming “I can never come back from there.” The speaker’s electric drive certainly puts the “throbbing” (5) in the poem’s own “throbbing accordion,” only this accordion throbs like a bomb that will rupture the universe along with time. What makes this poem transgressive is the scope of the journey, the completeness of the speaker’s sublimation into the second person “you.”

The danger in sublimation comes to the fore as many of Kim’s speakers are uncomfortable, overstimulated, or worse, imprisoned, tortured, manic, or dead. For instance, the titular princess of the poem “Princess Nanglang” was, in South Korean mythology, murdered for breaking a drum that alerts her kingdom of military invaders in order to aid an attack by her husband. Her father murdered her for her trespasses. From the throes of the afterlife, the ghost of the princess comes to the speaker “drumming on the eye of a storm.” She “strikes down the noisy television station with a hammer,” reaching through, over, and inside the speaker (the medium between princess and the reader), until finally, the speaker’s “well inside” overflows and she resolves to “tear this drum and meet [her lover],” ready to defy her own father (again?), well aware of the violent consequences to come (29).

In “Eurydice Trapped in Print,” the speaker begins in stifled Kristevan abjection, lamenting a tear that will not leave, calling her body a prison that “fits her so.” The first stanza ends in the speaker’s sub-logical imaginings before sleep. In the next stanza, the speaker wakes (Now Eurydice? Speaker as Eurydice? Speaking from a dream?) describing the view from inside her page: “every morning a pupil / bigger than the window / rolls around my room.” Later, the speaker implores the reader for help to “be free of this world,” exclaiming, “Please for goodness’ sake cut me out with your pinking shears! / Free me from this print!” (40). By pleading for the reader to cut her out, the speaker challenges the reader: will you pick up your pinking shears and mutilate your book to help the speaker? This gesture traps the reader in a different kind of Mobius strip: the uncanny valley between the reader and the read.

Sueyeun Juliette Lee, in her review of All the Garbage of the World, Unite!, defines the South Korean concept of han as “a Job-ish long-suffering that drowns one in bitterness, anger, and melancholy that condense together into a red glory beyond tears” (Lee). I find Lee’s description, especially the phrase “beyond tears,” to be particularly enlightening to Kim’s work: her speakers so often cry (or fail to), leak, or sweat; however, for Kim’s speakers, the tear is never an end point (there is always a “beyond”). Just as in “Eurdyice Trapped in Print,” Kim’s poems end on moments of han that leaves action, the imperative (to) thrust, as a kind of burning sensation deep inside the reader, yes, along with a strange sense of glory that is, yes, a certain shade of red.

In other poems, A Drink of Red Mirror offers some of the most quiet, reverent examples of Kim’s work I’ve yet read. In the pleasurably vexing “She, Jonah,” temporal simultaneity comes back to the fore as a lost voice that has given birth inside the white whale exclaims about her newborn: “even though I haven’t been born yet / I’ve fallen in love” (7). Where, in many of Kim’s poems, the white whale’s stomach lining might have closed in around them only for them to come out the other end something else entirely, this speaker spends most of the poem in exquisite anticipation of the unborn “you” whom the unborn speaker has already birthed. Even the elements are excited: the “forest without a single leaf” calls to the baby, while “large snowflakes echo Want to see you, see you” (7). This poem’s ending brings to mind a stark reversal of Gabriel’s assured gestures toward collectivity at the end of Joyce’s “The Dead,” opting, instead, to voice a collective celebration of new life even as the speaker ends the poem unsure, asking “Oh, what do I do?” (7).

One of my favorites from the collection, “Detective Poem,” is as straightforward a meditation as I’ve read by Kim. Through the numbered sections, the speakers consider a distant visage that transforms from leaf to eagle to two embracing lovers to a fish out of water. The object of the speaker’s fascination is never revealed, however, the journey leaves the reader overwhelmed. By the end, the visage has become the progenitor of the speaker’s own (de)evolution, leaving the speaker thirsting for what is inside that primal being:

“When I meet you who still remembers

when you breathed with gills

remembers how the land sucked

the essence out of my body dried my gills shut

and made me thrash around

I want to drink the ocean in you” (59)

The speaker’s vision quest gives her life. In the penultimate line she declares “I AM ALIVE!” And, just as quickly as the scope of Kim’s speakers expand to contain multitudes (to use an American point of comparison), her speakers becomes contained by them, and the poem ends on the image of “a fish kicked out of the deep sea” (59), wriggling and drowning in the open air like a human with her mouth open in the water.

Compared to Don Mee Choi’s translations, this volume’s collaborative translation offers a subtly destabilized vocabulary, which makes the images read more iconic (as opposed to photo-realistic) than in Choi’s translated collections.* This creates a cartoony resonance in certain moments, such as a moth with a hangover from too much light in “Detective Poem,” or the police that become impressionistic splotches in a Bahktanian riot at the end of “Outside Seoul Arts Center,” or the various incarnations of a nightmare in “Room 1306.” This effect, when combined with the uncharacteristically specific locations in Seoul from the second half of this collection, makes the poems read like a surrealist cartoon about the city in the style of early Loony Tunes shorts, disorienting the reader in a way similar to Ashbery’s claustrophobic blending of realistic ephemera and animated phenomena in “Daffy Duck Goes to Hollywood,” if not with a bit more of a razor’s edge à la the comedic, yet violent physical comedy of Saturday morning cartoon runs.

This quality lends a cohesion to the images themselves, and acts as medium for the speaker’s myriad transformations. Together with Kim’s collapsing of time, A Drink of Red Mirror becomes a catalyst that fires every neuron in your brain simultaneously. As reader, you’re never fully able to comprehend the speaker because you are the speaker just as you are not the speaker. You’re thrust into moments of patriarchal invasion just as you’re thrust into moments of matriarchal celebration. As any good book should, this volume challenges and exhausts the reader and speaker alike. It leaves you vulnerable inside outside the mind’s eye. It leaves you in this intoxicating condition, somewhere between love and abjection, from which you may never (want) to recover.

* This spectrum is taken from, and elaborated on, in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, a book I find useful for reading poetry and comics alike.

Ryan Bollenbach is a writer with an MFA from University of Alabama’s creative writing program where he formerly served as the poetry editor for Black Warrior Review. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Colorado Review, Foundry, smoking glue gun, Bayou and elsewhere. Find his tweets @SilentAsIAm, more writing at whatgreatlarks.tumblr.com