bolt of tulle // sublime disgrace

When you look at a soft

ness and think of neon. Prodigal

body. The pride of looking

like another century; of emotion

al chiaroscuro. Tinkling light,

cracked canvas. Memory is an accomplishment

of texture. i felt the tongue

to be an act of genius; like a letter

from a dead person, it was aged

and anachronistic if taken out of its envelope.

i felt the tongue inside me, articulation

of an antique voice. No one

is going to speak for me. vince,

no one is going to speak for me. They can

say they see what i saw but i’m

light burning backwards, the opposite of a dying

star. A chant in reverse,

articulate in its reverb

alone. A tonguing: the speech of

feeling. Translation of erotica; limit

experience of looking

at opened lips. Of talking all

the time. vince, no one is going to speak

for me.

iron triangle // cacophobia

i hope your heaven isn’t boring.

i hope you heaved your mind out far enough

to look in the mirror and see someone else

crawling behind you: gel-like, unsocketed. Essentially,

i hope their image of you didn’t become. A single head

can contain a million dark red curls,

a bloody rose garden of filament, cuticle. i dislike it

when a dead thing is repurposed

as if it is not beautiful

already. They’d have us eat our own ash.

They take one hand and spin

the spiral to convince us to dye it blonde.

vince, after i leave tell them not to turn me in

to something else. Don’t let them say I was a pretty

girl. Don’t let them make me a part of the death industrial

complex, a thingish photo

of what everyone else should want to be. As if

i meant for anything

except that my cult should stop seeing the echoes

of others; should float.

poltergeist i

my cult gathered around a dressmaker’s dummy. there were about twenty of us; mostly girls, graduates of institutes of fashion, women who had been touched by someone on the underground. it was the late 70s. later on they would say i convinced them. but, of course, they already believed; they had already enrolled in a school that made ideas about appearance concrete. they already wanted to make something bespoke that would repeat and repeat. vince, after the shell of my body dissolves around the part of you i swallowed, tell them what we did worked.

tell them it isn’t a cult if it works, if later on everyone is wearing it; tell them it isn’t a hospital if it produces the ill; tell them i was a charismatic economist, not a photographer; tell them i generated the need.

spiritually, we knew the value of a body after the fact; post-scarce. we knew that after what had happened to us we were not the raw body anymore, but something we could call a ghost; a mirror in a mirror.

(no, an automaton of ourselves sent to sit the portrait.)

(i mean, i hate a body in a white bag but i love the idea of a body in a bag. i mean, clothespins alone can be an outfit if you believe in points instead of frames.)

vince, there really isn’t anything to hold on to.

for our initiation we prayed to a sponge; we looked real close at our tan lines to try and decide where the darkness started and stopped; we knew we were living when our voices came out like theremin, when we could sense the fault lines moving under our feet. obviously, we wore veils. we wore polka dots. we made an argument out of patterns. when we went, we left an unsuicide note.

we made sure the coroner’s report evinced nothing. it became a thing later on, later when they were left with nothing but the image. have you heard of those women who get nude photos by telling the subject there is no film in the camera; by pretending the transaction is structural, composition emptied of content?; by suggesting the void to be filled was still owned by the men themselves? this was the inversion of us: what we did was more sinister: we left the camera and we left the film and we removed ourselves.

vince, we walked into the walls. we walked into the walls of the subway itself so there was nothing there to touch; all unreachable content. ungropable chants. our initiation ritual involved swallowing a lot of salt to become an ocean, to be a system that could create our own weather. the idea was that they could not permanently capture steam. our initiation ritual involved swallowing a corset to metabolize fashion, to excrete constriction. our initiation ritual replaced our bodies with the dressmaker’s dummy while we pulled a ghost from our mouths who pulled a ghost from her mouth who pulled a ghost from her mouth. factory of imprint; steam lick my eye.

Editors’ Note: “bolt of tulle//sublime disgrace” and “iron triangle//cacophobia” were originally published in Issue 5 of Sidereal Magazine.“poltergeist i” was originally published in Issue 8.1 of New Delta Review.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Candice Wuehle is the author of the full-length collection Bound (Inside the Castle Press, 2018) and the chapbooks Vibe Check (Garden-door Press, 2017), Earth*Air*Fire*Water*Æther (Grey Books Press, 2015) and curse words: a guide in 19 steps for aspiring transmographs (Dancing Girl Press, 2014). Poems from her collection, Death Industrial Complex, appear in Best American Experimental Writing 2020, Black Warrior Review, The Bennington Review, The New Delta Review, and elsewhere. She is originally from Iowa City, Iowa and is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Candice recently completed a PhD in English and Creative Writing from The University of Kansas, where she was a Chancellor’s Fellow. She currently resides in Lawrence, Kansas with her partner, musician Andrew Morgan.

ABOUT THE MANUSCRIPT

Justin Greene interviews Candice Wuehle:

1. What was the hardest thing about writing the poems in Death Industrial Complex? How did you handle it? What did you learn from the process?

The poems are written from the perspective of the photographer Francesca Woodman. I started writing DIC simply because I love her work—I love that it seems to be imagining something impossible and then making that impossible thing material. Her use of light, of long exposure, of a Vaseline blurred lens and of doubled bodies all insist on time as a shaping force, but at the same time these elements complicate what time is and therefore they complicate limits. Claire Raymond says that Woodman’s work displays a “mistrust of the bourgeois contours of commemoration” and I love that. There are a lot of ways to think about personal commemoration and memory (communal, travelling, prosthetic, traumatic, historic, on and on), but there are very few ways not to. For me her images exist in a multifaceted moment that resists the restrictions of linear time and therefore is disruptive of all kinds of restrictions—cultural, sexual, narrative, spiritual. Woodman said she made her photos so she could show people the world the way she saw it; in order to do that, I think she had to do a sort of conjuring of the space that image could exist within. So her work is always right after the limit experience—it isn’t about death or even birth, but what it feels like to exist after both. It isn’t the space of the page where the writer writes, it’s the idea that there’s a page to write on.

This is a long way of saying that the hardest thing about writing these pieces was a really anxious need to “perform” Woodman instead of writing Woodman.

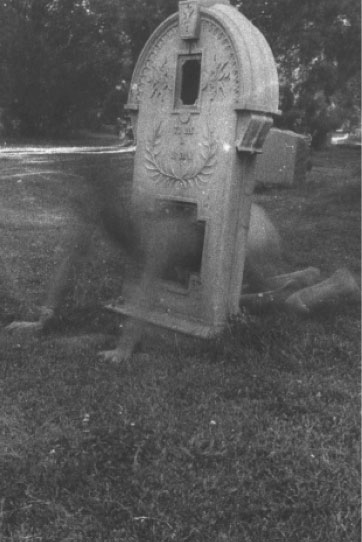

“Untitled.” Boulder, Colorado, 1972-75. Photography Francesca Woodman.

2. These poems interrogate the interrelationships between female bodies, fashion, mental health and violence, among other things. For example, in “poltergeist iii,” you write: “if you need the nurse to pay attention, bleed a fuzzy sweater. bleed a garter belt. bleed a sexy hat: a half veil.” How do you go about creating these nexuses of themes in such tight, evocative images?

I think a lot of it (again) has to do with resisting linear perception. The interrelationship between the ideas and images you listed are already so present to me in actual life; the boundary between, say, fashion, mental health and the body isn’t there for me as a line. The geography is very liminal. The images in “poltergeist iii” are a sort of temporal surrealism in the sense that the surreal makes the real more so because it is the real, but it’s saturated in the unconscious and therefore these moments layer each other. The series of “poltergeist” poems tries to let all the interior voices (conscious and unconscious) speak in those layers, at the same time. I was definitely thinking of the 80’s film when I titled these poems and of the way that, although the poltergeist has taken “possession,” it still has to manifest through it’s medium—the TV. If the ghost is the unconscious and the TV is the real, that interrelationship is immediately in conversation with so many layers of meaning. So, the “poltergeist” poems are trying to do the same—to talk with a lot of tongues in one mouth.

Poltergeist, 1982.

3. The voice of these poems is absolutely mesmerizing, how it conjures a hyper-vivid sensorium of cult ritual and memories with vince, how there can be levity and tenderness and immense disquietude so proximal to each other, or even happening all at once. What does speaking from the voice of a cult leader allow you as a writer? And having vince as an addressee?

I love this question. Vince is from Woodman’s “Self-portrait talking to Vince,” which is the first Woodman photograph I became interested in. I love this photograph because you can’t tell if the spiral (it’s a phone cord) is going in or coming out—is Woodman in the possessed or the possessor? Is she the body or the ghost? She’s both. And, therefore, so is Vince. I found Woodman’s own title tender. I spent a long time thinking about the idea of taking a photo of talking to someone who isn’t in the photo—it’s a form of reversed vocality—it seems generous, it seems not just to leave room for the other’s voice, but to put pressure on the act of listening. Also, it seems obvious that this is a portrait about connection that questions the very idea of psychic separation. That’s sort of a sentimental, romantic idea in the idiomatic sense of “being of the same mind and heart,” but it’s also frightening to suggest separation doesn’t exist. In some ways, I wanted to write from the voice of a cult leader because that made room for the extreme, intrusive authority possessed by those that occupy the physic lives of others. And on the totally other hand—I wanted to think about the energy of being a cult and of being occulted, of being so merged with others that you yourself are not individuated.

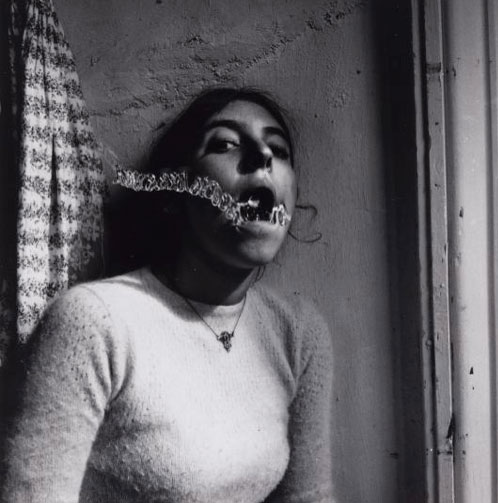

“Self-portrait talking to Vince.” Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-78. Photography Francesca Woodman.

Justin Greene is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at UC Berkeley. His work appears or is forthcoming in Barrelhouse and Hobart. He serves as a small press editor at Entropy, where he organizes the Where to Submit list.