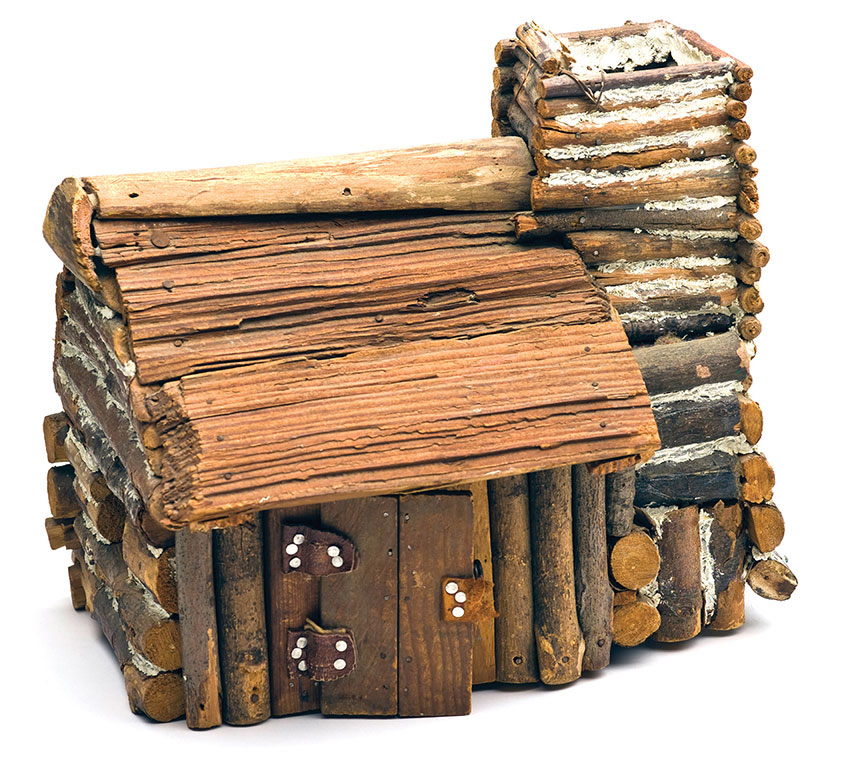

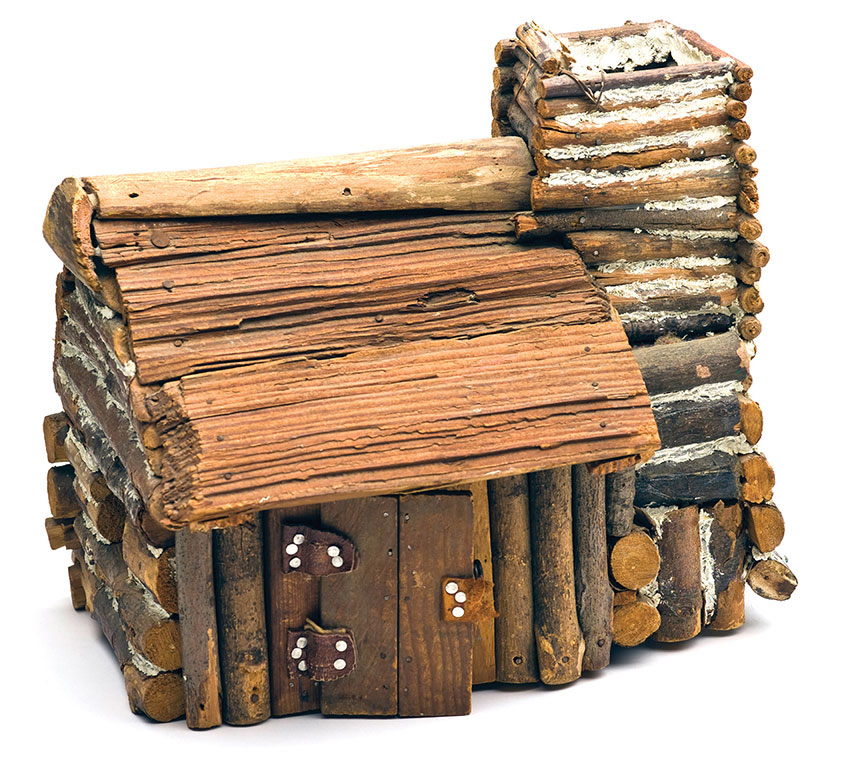

Grandpa’s Cabin

Bud kept a war diary. At seventeen, he joined the Navy, and was sent to France where he wielded a rifle capable of firing multiple rounds. Though he inhaled enough mustard gas to give him emphysema, he loved to smoke cigars. A bald man, Bud had a large freckle on the top of his head. He pointed to the freckle and told his grandchildren, “This is a nail head. The nail holds my head on.” His wife, Dot, draped dollies over the backs of all the armchairs in the living room. She said to her grandchildren, “The dollies absorb the grease from Bud’s head.” When Bud retired he didn’t know what to do, so Dot told him to pick up sticks in the adjacent vacant lot. From branches and twigs, he built the cabin. His granddaughter adored the small leather hinges, the tiny metal screw eye as doorknob. As a young child, she loved looking through the small cabin windows, admiring the small rooms that suggested the possibility for small people to live inside. Once, when she was in college, and many years after Dot had died, her grandfather pushed his tongue into her mouth during a goodnight kiss. She jerked back, and hurried off to join her friends at their campsite on the Florida shore.

Uncle Ebby and Uncle Reese’s Slot Machine

On their bar, beside the bourbon and vodka, the slots. And a crock of buffalo nickels. Uncle Ebby—he’d always tell you what he thought, good or bad. That’s a decorator for you. Uncle Reese used to relax with a Pall Mall and a vodka tonic before cooking. He’d set the table with the best china, silver, and crystal. Wine with dinner and a stinger afterwards. Their seven-year-old niece played the slots. A green machine with three spinning reels out of Atlantic City. She’d spend summers in their central A/C, watch their TV with more than three channels. Every Christmas, the uncles had two trees. One full of antique ornaments, the other upstairs, white flocked, red velvet ribbons and birds. Ever the gift, the winter coats, for her and her brothers. Later, she’d stand at the bar drinking quinine, sliding the coins into the slot—Bell Fruit Bell Fruit Bell Fruit. Jackpot.

Mom’s Scapular

She was the most devout Catholic in the South, a single mother who worked three jobs and double-shifts. She wore this scapular all day (except when bathing) during her oldest daughter’s nine-month coma. Mom became obsessed with Mary sightings, drove the family to see Nancy Fowler, the visionary of Conyers, GA, where the Virgin Mary sometimes appears in a farmhouse or sometimes as a sign in the sun. Katherine, her youngest daughter, remembers the spectacle: 30,000 people in a cow pasture, the Rosary prayed in four languages, “live” Stations of the Cross, and Polaroids of the sun at noon. She kept her smart mouth quiet on the drive home. The faithful believe if you’re wearing a scapular when you die, it’s a fast track to heaven, no stops in Purgatory.

Grandpa’s Cabin

Bud kept a war diary. At seventeen, he joined the Navy, and was sent to France where he wielded a rifle capable of firing multiple rounds. Though he inhaled enough mustard gas to give him emphysema, he loved to smoke cigars. A bald man, Bud had a large freckle on the top of his head. He pointed to the freckle and told his grandchildren, “This is a nail head. The nail holds my head on.” His wife, Dot, draped dollies over the backs of all the armchairs in the living room. She said to her grandchildren, “The dollies absorb the grease from Bud’s head.” When Bud retired he didn’t know what to do, so Dot told him to pick up sticks in the adjacent vacant lot. From branches and twigs, he built the cabin. His granddaughter adored the small leather hinges, the tiny metal screw eye as doorknob. As a young child, she loved looking through the small cabin windows, admiring the small rooms that suggested the possibility for small people to live inside. Once, when she was in college, and many years after Dot had died, her grandfather pushed his tongue into her mouth during a goodnight kiss. She jerked back, and hurried off to join her friends at their campsite on the Florida shore.

Uncle Ebby and Uncle Reese’s Slot Machine

On their bar, beside the bourbon and vodka, the slots. And a crock of buffalo nickels. Uncle Ebby—he’d always tell you what he thought, good or bad. That’s a decorator for you. Uncle Reese used to relax with a Pall Mall and a vodka tonic before cooking. He’d set the table with the best china, silver, and crystal. Wine with dinner and a stinger afterwards. Their seven-year-old niece played the slots. A green machine with three spinning reels out of Atlantic City. She’d spend summers in their central A/C, watch their TV with more than three channels. Every Christmas, the uncles had two trees. One full of antique ornaments, the other upstairs, white flocked, red velvet ribbons and birds. Ever the gift, the winter coats, for her and her brothers. Later, she’d stand at the bar drinking quinine, sliding the coins into the slot—Bell Fruit Bell Fruit Bell Fruit. Jackpot.

Mom’s Scapular

She was the most devout Catholic in the South, a single mother who worked three jobs and double-shifts. She wore this scapular all day (except when bathing) during her oldest daughter’s nine-month coma. Mom became obsessed with Mary sightings, drove the family to see Nancy Fowler, the visionary of Conyers, GA, where the Virgin Mary sometimes appears in a farmhouse or sometimes as a sign in the sun. Katherine, her youngest daughter, remembers the spectacle: 30,000 people in a cow pasture, the Rosary prayed in four languages, “live” Stations of the Cross, and Polaroids of the sun at noon. She kept her smart mouth quiet on the drive home. The faithful believe if you’re wearing a scapular when you die, it’s a fast track to heaven, no stops in Purgatory.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jody Servon creates collaborative and socially engaged projects that encourage public interaction and personal exploration. Her projects have been included exhibitions, screenings, and as public projects in the U.S., Canada, and China. Servon’s writing and/or art has been featured in New American Paintings, Emergency Index, Kakalak, and Artful Dodge. Her collaborative work with poet Lorene Delany-Ullman has been published in AGNI, Tupelo Quarterly, Palaver, and Lunch Ticket. Servon received an MFA in New Genre from The University of Arizona and a BFA in Visual Art from Rutgers University. She has served on numerous boards including: Elsewhere Museum, North Carolina Museums Council and the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design. Currently she is the Sharpe Chair of Fine and Applied Art and Professor of Art at Appalachian State University in North Carolina.

Jody Servon creates collaborative and socially engaged projects that encourage public interaction and personal exploration. Her projects have been included exhibitions, screenings, and as public projects in the U.S., Canada, and China. Servon’s writing and/or art has been featured in New American Paintings, Emergency Index, Kakalak, and Artful Dodge. Her collaborative work with poet Lorene Delany-Ullman has been published in AGNI, Tupelo Quarterly, Palaver, and Lunch Ticket. Servon received an MFA in New Genre from The University of Arizona and a BFA in Visual Art from Rutgers University. She has served on numerous boards including: Elsewhere Museum, North Carolina Museums Council and the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design. Currently she is the Sharpe Chair of Fine and Applied Art and Professor of Art at Appalachian State University in North Carolina.

Lorene Delany-Ullman’s book of prose poems, Camouflage for the Neighborhood, was the winner of the 2011 Sentence Award, and published by Firewheel Editions (December 2012). She recently published her poetry and creative nonfiction in Santa Monica Review, TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Parentheses Journal, The Fourth River and Concis: A Journal of Brevity. Her poems have been included in anthologies such as Orange County, A Literary Field Guide (Heyday Books, 2017), Bared (Les Femmes Folles Books, 2017), Beyond Forgetting: Poetry and Prose about Alzheimer’s Disease (Kent State University Press, 2009) and Alternatives to Surrender (Plain View Press, 2007). She works in collaboration with artist, Jody Servon, on Saved: Objects of the Dead, a photographic and poetic exploration of the human experience of life, death, and memory. Delany-Ullman teaches composition at the University of California, Irvine.

Lorene Delany-Ullman’s book of prose poems, Camouflage for the Neighborhood, was the winner of the 2011 Sentence Award, and published by Firewheel Editions (December 2012). She recently published her poetry and creative nonfiction in Santa Monica Review, TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Parentheses Journal, The Fourth River and Concis: A Journal of Brevity. Her poems have been included in anthologies such as Orange County, A Literary Field Guide (Heyday Books, 2017), Bared (Les Femmes Folles Books, 2017), Beyond Forgetting: Poetry and Prose about Alzheimer’s Disease (Kent State University Press, 2009) and Alternatives to Surrender (Plain View Press, 2007). She works in collaboration with artist, Jody Servon, on Saved: Objects of the Dead, a photographic and poetic exploration of the human experience of life, death, and memory. Delany-Ullman teaches composition at the University of California, Irvine.

ABOUT THE MANUSCRIPT

We have collaborated on Saved: Objects of the Dead since 2009. The project is comprised of forty-three color photographs of material possessions people have saved after the death of a loved one. Each image is paired with a prose poem that is based on interviews with the people who have kept each item. The project is an empathetic exploration of the human experience of life, death, and memory. Saved chronicles the lives, deaths, and relationships of individuals whose objects are imbued with their emotional and physical senses, then cherished as an affirmation of their lives.

This project is a collaborative work not only between the artist and author, but also with those who participate by lending their objects to be photographed and tell us their intimate, provocative, and embarrassing stories about themselves and their departed loved ones. We preserve the legacy of the dead in both word and image, a photographic and lyric expression of the indelible imprint they have left behind. As humans, we experience loss throughout our lives. How we respond, empathetically or not, to these losses as individuals, communities and society impacts our daily lives in small and large ways. Saved represents a communal and outward expression of grief while addressing the universality of how objects, mementoes, and heirlooms embody the otherwise abstract emotions of loss and memory. The photographs and prose poems raise questions about the nature and function of remembrance, the consumer status of the remembered items, and the way that what may seem to be the “stuff” of our lives becomes imbued with symbolic density and even new life. This work is a mixture of object, ethnography, and language combined with a sense of personal intimacy that addresses our human mortality.

Saved has been exhibited in over twenty-five art galleries and museums nationwide, and excerpts have been published in five literary journals. At these exhibitions, people have shared intimate stories about their deceased loved ones with the us. The act of sharing the death of a loved one helps mitigate the traditional boundaries that death and mourning affords us, allowing for deeper personal and public relationships with the bereaved and the dead. The photographs coupled with the prose poems often engender genuine and heartfelt communication about loss that is not otherwise possible for some people.

We believe the project crosses many genres such as art, literature, lifestyle and popular culture, memoir, history, biography, and personal development. The candid and direct style of both the photographs and the prose poems transcends gender, age, occupation, marital status, and religious beliefs. Thus, the literary, photographic, and artful quality of our project makes it sharable with an audience larger than a grieving public.

Editors’ Note: The excerpts above were previously published in AGNI #74.

ABOUT THE MANUSCRIPT

We have collaborated on Saved: Objects of the Dead since 2009. The project is comprised of forty-three color photographs of material possessions people have saved after the death of a loved one. Each image is paired with a prose poem that is based on interviews with the people who have kept each item. The project is an empathetic exploration of the human experience of life, death, and memory. Saved chronicles the lives, deaths, and relationships of individuals whose objects are imbued with their emotional and physical senses, then cherished as an affirmation of their lives.

This project is a collaborative work not only between the artist and author, but also with those who participate by lending their objects to be photographed and tell us their intimate, provocative, and embarrassing stories about themselves and their departed loved ones. We preserve the legacy of the dead in both word and image, a photographic and lyric expression of the indelible imprint they have left behind. As humans, we experience loss throughout our lives. How we respond, empathetically or not, to these losses as individuals, communities and society impacts our daily lives in small and large ways. Saved represents a communal and outward expression of grief while addressing the universality of how objects, mementoes, and heirlooms embody the otherwise abstract emotions of loss and memory. The photographs and prose poems raise questions about the nature and function of remembrance, the consumer status of the remembered items, and the way that what may seem to be the “stuff” of our lives becomes imbued with symbolic density and even new life. This work is a mixture of object, ethnography, and language combined with a sense of personal intimacy that addresses our human mortality.

Saved has been exhibited in over twenty-five art galleries and museums nationwide, and excerpts have been published in five literary journals. At these exhibitions, people have shared intimate stories about their deceased loved ones with the us. The act of sharing the death of a loved one helps mitigate the traditional boundaries that death and mourning affords us, allowing for deeper personal and public relationships with the bereaved and the dead. The photographs coupled with the prose poems often engender genuine and heartfelt communication about loss that is not otherwise possible for some people.

We believe the project crosses many genres such as art, literature, lifestyle and popular culture, memoir, history, biography, and personal development. The candid and direct style of both the photographs and the prose poems transcends gender, age, occupation, marital status, and religious beliefs. Thus, the literary, photographic, and artful quality of our project makes it sharable with an audience larger than a grieving public.

Editors’ Note: The excerpts above were previously published in AGNI #74.