What happened between or out of or in the holes of the story is the real story. What cannot be filled in with sod or whisked away with dust. Because history is neither the truth as it happened nor necessarily the truth we most want to believe. When I look at the family tree I see so many faceless names skewered on ascending boughs, making whole orchards of molding fruit, a hodgepodge of known or estimated dates, origins, migration patterns. I can imagine these known and unknown ancestors in graveyards reaching out across the oceans—to West African villages where someone was kidnapped venturing too far from the fold or was captured in a battle, a raid, enslaved, sold; to the farms and teeming cities of Western Europe, where a “heretic” fled for religious freedom, or a younger son got dizzy on the rumor of fortune, or men and women left in ones or twos or whole families trickling in on steerage, to escape the farm, the shop, the lord. Most of their stories I do not know—but I see these faceless, often nameless ancestors arriving at a harbor (Charleston? Baltimore? New York?)—free and ecstatic or subdued by the prospect of endless work, the unknown land; or staggering onto a deck with shackles boring bloody welts into their skin, stunned by the sudden light, their languages ricocheting off each other, and when forced to bend to the master tongue, still maintaining some of their posture. In the centuries that follow, occasionally someone leaves a diary full of holes, and you glimpse a personality, a record shaped, curated for “posterity.” History belongs to the victor? Perhaps to the one with the loudest pen. (So forced illiteracy has historical ends.) Mythology grows in the distance between record and memory over several generations so that a farm becomes a sawmill and a slave woman embarks on an unlikely thousand-mile journey (declining a chance at liberty) to visit her master, a Confederate prisoner of war, who promises a great reward.

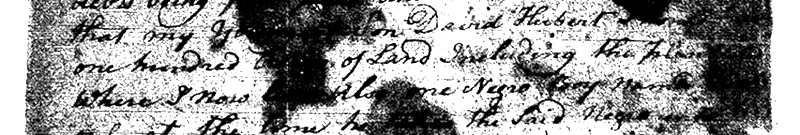

What I know is this: Sometime before 1746, Benjamin Hubert, a French Huguenot, arrived in the “New World” with his desperation and his faith. But the path from persecuted to persecutor is as narrow as the slave trader’s whip. In his will, recorded in Georgia in 1793, Hubert left his youngest son 100 acres, including a plantation, and “one negro boy named Rob.” By 1798, Benjamin Hubert’s oldest son Matthew owned six slaves. Half a century later, Matthew’s son William was still in Georgia, the owner of a plantation and the fifty-six human beings whose labor supported it. William Hubert’s daughter, Martha, had married J.A.S. Turner, a wealthy Georgian whose family’s plantation, Turnwold, and its slave inhabitants, were the source of the Uncle Remus stories.

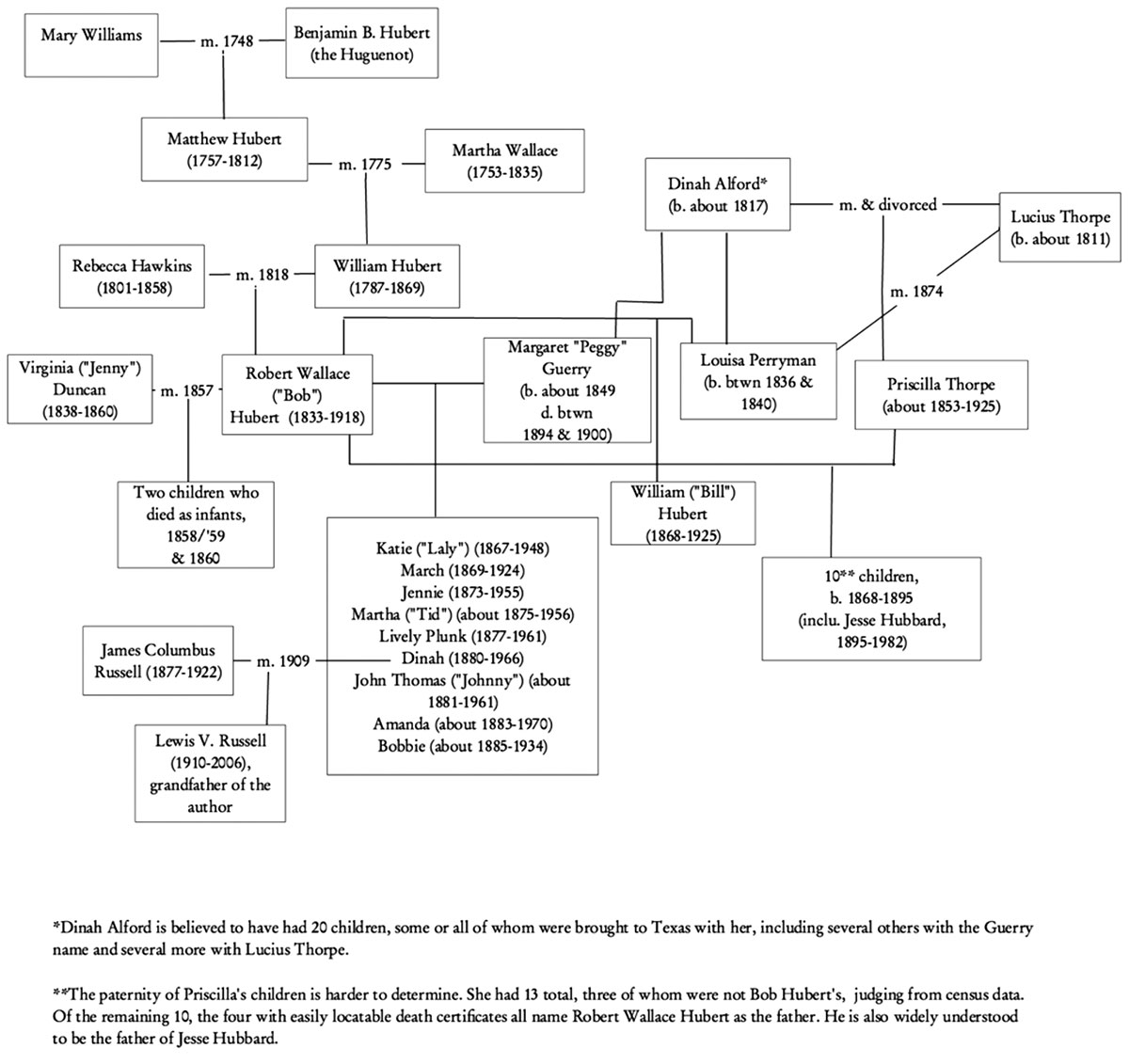

Turner had taken a fancy to Texas as a Captain in the Mexican War, riding hard on the heels of Manifest Destiny. His own destiny manifested in the form of an exodus. When the Republic of Texas won independence from Mexico in 1836, it used land as currency to pay soldiers and encourage settlement, and after it was annexed to the United States in 1845, Texas continued to dole out land at about 50 cents an acre. By the mid-19th century, white settlers were invading the state like an Old Testament plague. But the Native inhabitants they drove away weren’t headed for any land of Canaan. In 1854 the State of Texas purchased the land of the Alabama in Polk County and settled the tribe onto a thousand-acre reservation that became even more crowded once the Coushatta were likewise dispatched there in 1859. That year the rest of Texas’s Native inhabitants were banished to Oklahoma, opening their land for white settlement. By then the Turners had already headed West, and out of family feeling or an itch for land acquisition, the Huberts had decided to come along. Among the many human possessions they brought to Texas was the slave Dinah Alford, a mother of twenty. Three of Dinah’s daughters—Margaret, called Peggy; Louisa; and Priscilla—would have children by one of the Hubert sons—Robert, called Bob—after his return from the Civil War. One of those children was my great-grandmother.

I am not writing a history of what happened, which I cannot know. I am writing into the silences, the omissions, what has been left out either deliberately or because by its nature it resists visibility. I am writing into the space where one story trails off and another begins, oddly muddled, or between what some might have thought and what they dared to utter, or beyond what no one was sure of but everybody recollected, or within what only I imagined, bent over a photocopy of a photocopy of my great-great-grandfather’s diary and a stack of books and records, trying to fill in the letters between H and P. This is not a history or a fiction. I would like to invoke Audre Lorde’s term “biomythography” and puncture its seams, pull out its hem, and make “biomythology” from the swaying threads. Thus there may be several versions of the same events. None may be true but all could have been—climbing a web of omission, legacy, myth.

Were you a tear in her life, the kind

that starts with a moth hole and rips

to the seam overnight? She was sixteen

and newly freed, your cook and once

your slave. Was she peeling potatoes, shelling

peas, bent over an open flame in some back-

house kitchen when you came from behind

and prick!—your beard like brushfire

at her neck, how in battle exploding shells

set the wilderness and shrieking wounded alight.

Q: So how did the women feel about this?

A: Don’t guess they had no say.

Notes:

This excerpt first appeared in The Brooklyn Rail. “Heard a whippoorwill” was republished on the NEA’s website.

The will of Benjamin B. Hubert is in Warren County, Georgia, Will Book 1 (1798-1808), archived at the Washington Memorial Library in Macon, GA.

The sentence “I am writing into the silences, the omissions, what has been left out either deliberately or because by its nature it resists visibility” is language derived from a prompt Dawn Lundy Martin gave our graduate workshop at the University of Pittsburgh in 2013.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lauren Russell is the author of What’s Hanging on the Hush (Ahsahta Press, 2017). A 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellow in Poetry, she has received fellowships and residencies from Cave Canem, The Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, VIDA/The Home School, the Rose O’Neill Literary House, the Millay Colony for the Arts, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and City of Asylum/Passa Porta. Her chapbook Dream-Clung, Gone came out from Brooklyn Arts Press in 2012, and her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, boundary 2, the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, The Brooklyn Rail, jubilat, Cream City Review, and Bettering American Poetry 2015, among others. She is a research assistant professor and is assistant director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics at the University of Pittsburgh.

ABOUT THE MANUSCRIPT

In 2013, I acquired a copy of my great-great-grandfather’s diary. Robert Wallace Hubert was a Captain in Hood’s Texas Brigade in the Confederate army. After his return from the Civil War, he fathered twenty children by three of his former slaves, who were also sisters. One of those children was my great-grandmother.

As I transcribed the 225-page diary, I became interested in its omissions and decided to write into the space of what is missing. The result is Descent, a book-length reckoning with this part of my family’s history. As I dug through records, travelled to East Texas to meet relatives I did not previously knew I had, and investigated my relationship to race and legacy in this era of police brutality, Black Lives Matter, Confederate flag controversies, and the ascent of a President Trump, living with the project became part of the project itself. Thus I began to experience time as blurred, and the book is not a linear progression from the nineteenth century into the present but an experience of wandering across and within time.

In my effort to write into and through silences, I have wound my way through substantial peripheral research, but since much of what I know comes to me via Hubert himself—his diary, his military records, even his grades—I also want to imagine the voice of my great-great-grandmother Peggy Hubert, a black woman silenced by history. Descent is a hybrid work of verse, prose, images, documents; traditional and innovative forms. The range of approaches underscores the impossibility of ever really knowing or containing history within a single narrative. As I have said in many statements, “Descent is at once an investigation, a reclamation, and an insistence on making history as a creative act.”