September 1945 Yokohama

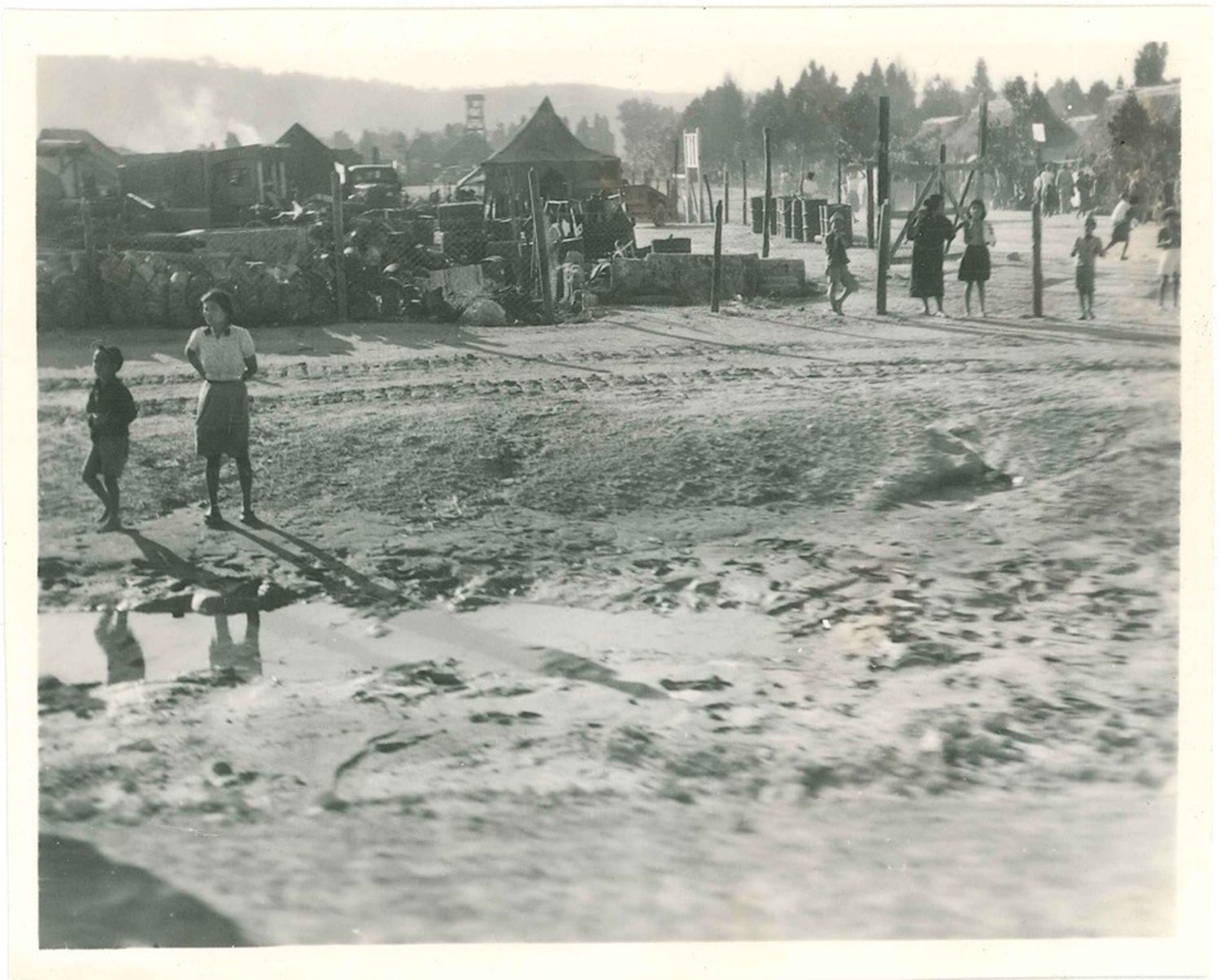

(It starts as soon as Americans landed in Okinawa in late March 1945. Rumors of rape are whispered, of women disappearing. As soon as surviving women and children are ushered into civilian camps like scared sheep, trading of flesh starts: an extra bowl of food for a fuck, or American soldiers coming to barbed-wire civilian camps, demanding women. No woman goes to the bathroom by themselves and especially at night because they know that’s when they are the most vulnerable when darkness hides anything and anyone. And soon enough, gongs made out of empty artillery shells are banged at all hours. Whenever Americans come into their camps, gongs are banged, warning women to hide.)

Okinawan Civilian Camp 1945

And as soon as the Emperor’s shaky voice rose and fell on the radio on August 15, 1945, officials know what they have to do. They know what happens to a defeated country, an occupied country. They know, first hand, because they themselves know what their men did in China, in the Philippines, in Burma, in Hong Kong, in Singapore, in areas they occupied and lost. They know what their men did, and they know what men in general do to women because men can’t live without sex, men are different from women, all the arguments that were used during the war in sanctioning comfort stations, both official and unofficial. So with nearly 50 million yen of “loan” from the Japanese imperial government, they name themselves Recreation and Amusement Association, and start designing the state sanctioned brothel system for the Occupying Force.

They know there are only two kinds of women: good and bad women – mothers and daughters, and whores. Good women must be protected. Whores are replaceable: a vagina is a vagina, not a person. They know what they have to do: just like in China, just like in former occupied territories in Southeast Asia, few bad women have to be sacrificed to protect the chastity, the purity of the good women. They look at their wives and daughters, and they would do anything to protect them; at night, they might go to their mistresses’ homes. Because they knew themselves to be of two minds, they also know that men all over the world shared their beliefs about women.

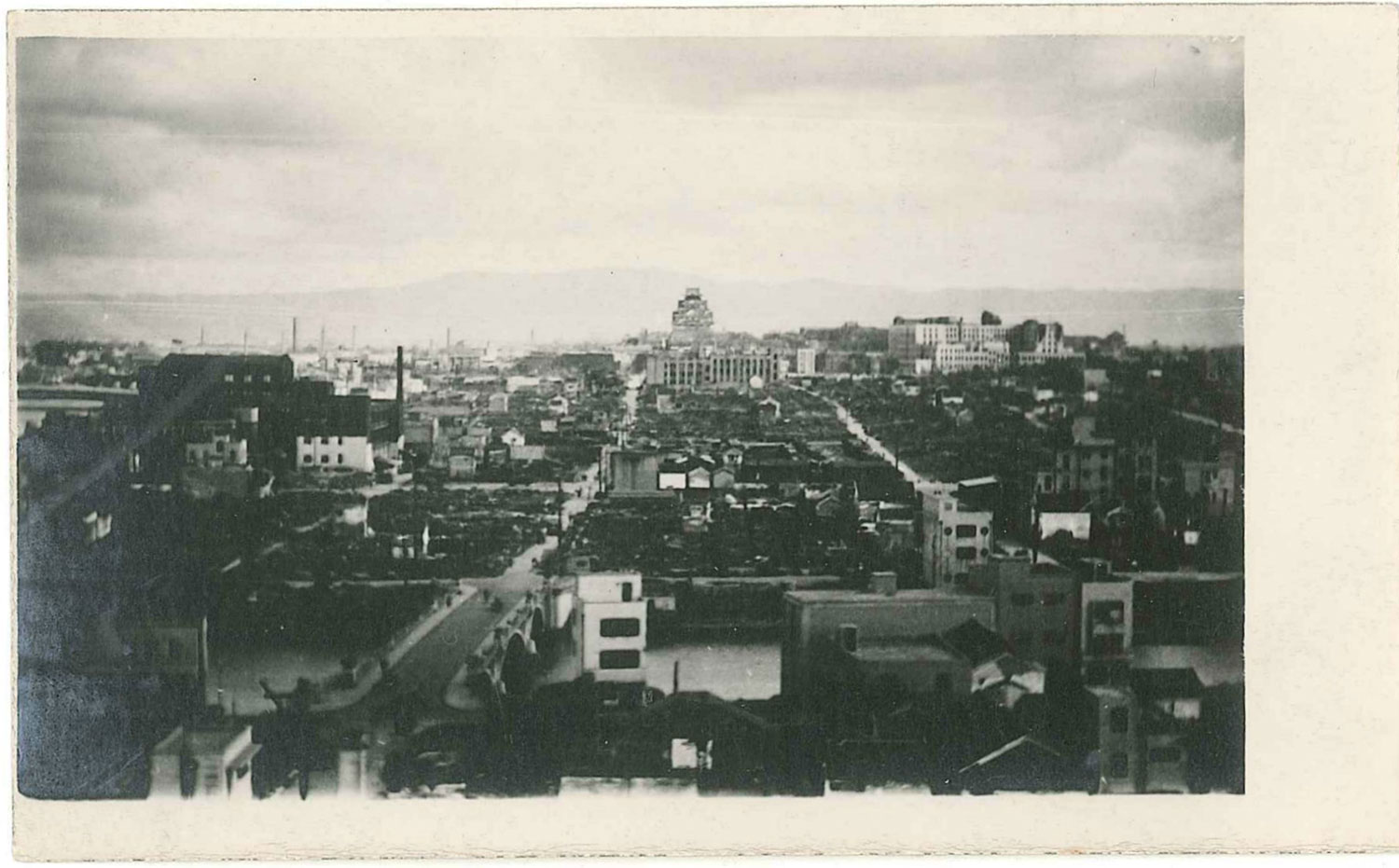

Osaka November 1945

Women are told, “American soldiers are awful… I heard they did pretty awful things in Okinawa and Saipan. Young girls should hide themselves somewhere in the mountains as quickly as they can.”¹ Women are told, “American soldiers kill all men and rape women.”² Women are told never to wear skirts, to avoid Americans as much as they can, don’t wave or smile at the Americans.³ Women in cities are told to evacuate to the mountain sides and hide as long as they can.

Osaka November 1945

It is 2:05 in the afternoon. He steps down from the plane with a corncob pipe in his hand, a hero’s welcome, a John Wayne arriving in town on his horse after a shootout in the desert. A big man in his aviator sunglasses, relaxed as only a victor can be. The Japanese planes lie disassembled, propellers taken off, wings clipped like earthbound turkeys. They will not fly, but to the General, what is around him does not matter. Not the defeated Japanese soldiers. Not the soldier who, two weeks ago, tried to resist. He walks down the steps. As he is driven on a jeep, rows and rows of Japanese soldiers still in uniform stand at attention, facing away from the procession, facing away as they have done for the living god. And women have cut off their hair, fearing rape. Men afraid of being castrated. They hide in their houses, afraid to breathe, afraid to look out the window, the American devils will rape, castrate, destroy. America is here to rule the vanquished land.

Tokyo Ruin 1945

Tokyo lies in ruins. Bombed-out people hurriedly make shacks out of lumbers from their neighbors’ burned-down houses. Children are shipped back from their evacuations, only to find themselves orphans. Girls working on ammunition factories find out that their families have all died, or that there is no way to go home because railroad tracks have all been bombed or made useless. They walked about as ghosts, half here, half there, their future unknowable and their present desperate.

Okinawan Women 1945

After the voice of the Emperor at noon only a few days ago, people are changed. They no longer answer the call of the nation, but only to themselves as they stand in the ruined cities. People push others for water, people push others off the trains, people push others so that they can survive, just one more day. Charred bodies lie on the streets, and they walk atop them as skulls and bones crumble under their weight; people build shelters from someone else’s misfortune, squat on land because there is no one to claim it. They have woken up from a long dream, and what people see, whether they like it or not, is their true selves, self-centered, greedy, merciless, and what matters is not the past, of the lost war, the surrender, but this moment, and how to ease hunger.

Signs appear all over Ginza, on newspapers, We require the utmost cooperation of new Japanese women who participate in a great project to comfort the occupation forces, which is part of the national emergency establishment of the postwar management. Female workers, between 18 – 25 years old, are wanted. Accommodation, clothes, and meals, all free.⁴ And girls all over, girls who have lost their parents in air raids, young women who lost their husbands, girls who must take care of their young siblings, answer the call, 1,500⁵ or 1700 of them within the first few days, not knowing what is to be demanded of them, not understanding what the government has done during the war, drafting in registered Japanese prostitutes and kidnapping women from occupied areas to comfort the imperial soldiers. The war is over, and men in the government know that all men need women, whether you are Japanese or American or white or black, all men need women to fuck, during war or during peace time. So instead of men raping good Japanese women, as Japanese men had done in Siberia, in China, in Indonesia, in the Philippines, they would create a barrier, professionals to take care of the need. And these girls, without knowing what will be demanded of them, answer the call for shelter, for money, for food, for jobs, but not for the country as they had done only a few days before.

¹ Tanaka, Kimiko. Onna no Bohatei (Female Breakwater). Tokyo: Daini Shobo, 1957. 田中貴美子『女の防波堤』第二書房1957(11)

² Tanaka, Kimiko. Onna no Bohatei (Female Breakwater). Tokyo: Daini Shobo, 1957. 田中貴美子『女の防波堤』第二書房1957(13)

³ Shufu no Tomo. August 1945.

⁴ Dower, John. Embracing Defeat.

⁵ Shimokawa, Koushi. “Haisenkoku no Onnatachi ga Mita Yume: RAA to Panpan Girl no Jidai” (Dreams as Experienced by Women of the Vanquished Country: The Era of RAA and Panpan Girls). President October 1999 Vol 37 (9): 246-251.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in Tokyo, Japan and raised in Europe and America, Mariko Nagai has received fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center, UNESCO-Aschberg Bursaries for the Arts, Akademie Schloss Solitude, among others and has won the prestigious Pushcart Prizes for both in poetry and fiction. Mariko Nagai is the author of Histories of Bodies: Poems (2007), Georgic: Stories (2010), Instructions for the Living (2012), and Irradiated Cities (2017), as well as two verse-novels for children. Nagai is an Associate Professor at Temple University Japan.

ABOUT THE MANUSCRIPT

A girl packed a small bundle and pressed it against her body as she hid in the coal storage in the bottom of a ship heading toward Shanghai or Hong Kong, only to be auctioned off to Singapore, Manila, Borneo, Thursday Island, Rangoon, Bombay, as far away as Madagascar and Cape Hope, to places she never knew existed. Another girl, thirty years later, was taken from a village in Korea with a promise of a better job and even an education, only to be herded into the Japanese Imperial Army ship simply labeled as “military supply” in the account book, taken to remote areas such as Rabul, Burma and Okinawa where Japanese Army and Navy occupied. Here she served men for one yen, and was left to fend for herself when the Army began to retreat. She strapped herself with useless military-issued money and tried her best to survive in a hostile land where she did not know the geography or have the language or food to survive. And as soon as the war ended on August 15, 1945, the Japanese government, fearing that soon-to-be-landing American soldiers would rape innocent women, called for the “New Woman” to comfort the Americans, just like they did the Japanese soldiers, and girls who lost their families in the air raids, girls who were left stranded without homes, answered the ads in the hope of surviving. They earned 200 yen, the price of a black-market packet of Lucky Strike. Sometimes, American men would give them two packs for the service, and in exchange, they opened their legs to accommodate these soldiers who were known as “the white devils” during the war. Karayuki-san. Rashamen. Comfort women. Special Women of RAA. Panpan. Only-san. Different names, different times, but all of them having one thing in common: their bodies became commodities – cheap commodities – that could be sold off, bartered, discarded at the whim of men. This work-in-progress, Bodies of the Empire traces the history of Japanese sex workers – both government-sanctioned and freelance, from 1868 when Japan emerged out of its 300 years of isolation to 1953, a year before Japan became an independent nation-state and the year when prostitution was finally illegalized. Weaving together travelogues of writers, historical documents and their own words, this creative nonfiction project explores the lives of these women who moved through the world selling their bodies—the only commodity they could sell. This creative nonfiction project attempts to excavate the voices and experiences of these women who have been forgotten.