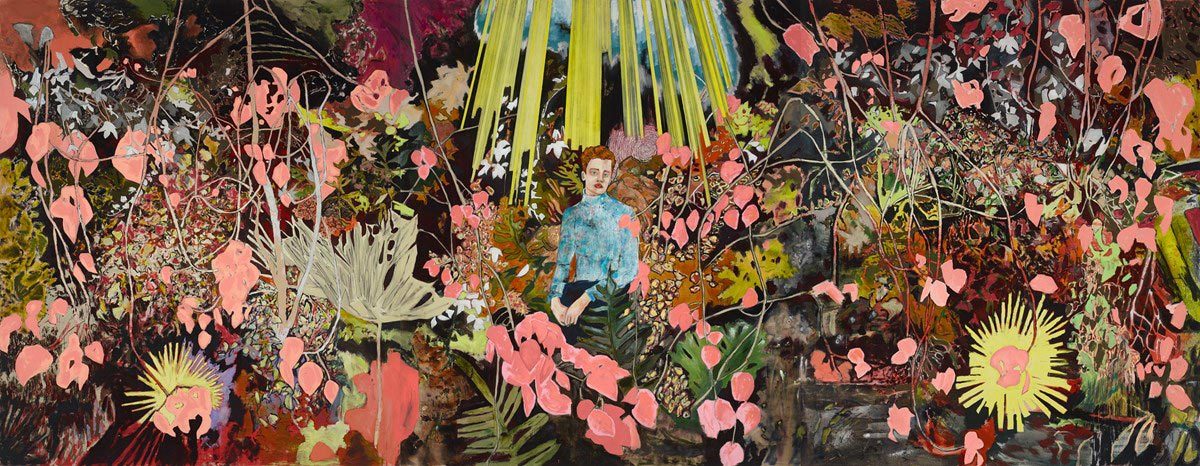

HERNAN BAS

The Guru, 2013-2014

Acrylic on linen, three canvases

84 x 72 inches

Lehmann Maupin Gallery

The house was built with concrete, and its walls were never painted. It was a damp gray, inside and outside. The only thing with color was the curtain, the light pink curtain with deep pink dots. Pink that is pinker than pink, what an artificial color. Outside the window lay ladders, painted in black. I walked out to the garden with a bucket of water past the wire fence. In the garden taro leaves grew tall and big and underneath were multiple terrariums where plants with long and narrow leaves lived. Through the terrarium we could see roots that were longer and bigger than expected. I watered the plants using one fifth of the water that I brought in my big water bucket. Afterwards I sat down on the foldable chair in the garden. It was a hot day indeed. I slid my body down the chair until my shoulders reached the edge of the chair’s back. Hiding my face underneath the taro leaf I felt hazy.

I am not entirely sure whether I was asleep or I’d just spaced out. I was watching the house, the desaturated building with gray wall and black ladder leaning beside it, and only pink beaming as it was shining. With its pale pink color and the pinker pink dots popping here and there on the curtain, the pinker pink seemed to grow bigger, and bigger, and bigger. It grew bigger than the curtain, bigger than the window, bigger than the house, and it finally filled out my eyesight with pinker pink. Startled by the pinker pink I was shot back to reality. In front of my face was the flamingo’s butt. It put its butt up high to tilt the neck down, and drank the water from the bucket I’d brought. There were two other flamingos drinking from the water fountain in front of the gray house.

It was their drinking time. Soon it would be their meal time. Dad had been preparing their meal for half an hour.

The town was a dull place. Peaceful and therefore boring. It almost felt like time stopped in this place. People napped in the middle of the day, the sunrays making them doze off. Or maybe discerning a difference between sleeping or being up was not a thing in this place. My duty was to water the plants and flamingos, for plants occasionally and for flamingos three times a day. And clean up their shits on the ground. Flamingos smelled funky and warm.

The door opened and a guy wearing a washed-out yellow T-shirt that looked so soft and thin that you could almost see his skin beneath appeared. He was holding the bucket of mushy food he made for the flamingos. He blinked his big blue eyes and his eyelashes so blonde that sunrays could travel through them. He was all sweaty. The buckets were warm, oozing vapors.

“There is my son,” he said. When he smiled his eyes folded downwards which made his smile almost indiscernible if his mouth was not arching up. I stood up and turned my back to him and walked toward the forest. I knew what he would do without seeing him. He would just blink slowly and look at me and then turn around and pour the flamingo food into their bowls and wait for them to come. And he would shout out, “Don’t go too close to the End of the World! It is dangerous!” when I’d already walked so far away I could barely hear his voice.

I walked deep into the forest, towards the End of the World where the land gets pixelated and crumples down. Unexplainably, plants looked different here, though just the same plants out everywhere. The closer I got to the End of the World things felt more and more odd. But might not be odd. And there was a pond. I don’t know whether to call it a pond as the water falls off at the edge of it, where the land ends. And the water falls down, to the dark depth. This was the only place that interested me, which was so much less dull than anywhere else. Especially when standing on the edge, it was exciting and terrifying, not knowing what was down there, and what would happen when I fell. But I would never really try to jump off. Still, the idea of the edge itself was exciting. I didn’t do much there. I ditched some dirt, watched some mushrooms that were probably poisonous, and dipped my legs into the pond. When it was time for me to water the flamingos I walked back to the farm. The cue was the sunset. When the sky is red, it is the time.

When I came back Dad was sitting among the flamingos. Flamingos were picking at his hair and he was so much shorter than them as he was sitting while the flamingos stood on such long legs. One of them, which he called Hoon, the weakest among the flamingos, sat on his lap and he was patting it. He always named all the flamingos, and I would never remember which was which as they looked almost the same for me. The reason that I recognized Hoon was because it was exceptionally small. My dad noticed me and he smiled with his eyes, which I ignored walking straight toward the water bucket and scooping up water from the well. It was the end of my day. Which would also start with filling up the water in the morning the day after.

I was raking the flamingo shit. You don’t rake it when it is freshly out of their buttholes. Let it sit and harden, and then rake it. Some people think flamingos would have magical pink poops, and they make meringue cookies with pink dyes and call them flamingo poop. But the reality is the nasty shit. I raked them grumpily. How perfect it is, in this warm weather and this perfect peace, to rake flamingo shits. After raking I grabbed the foldable chair and sat under the roof to avoid sunrays. It was time for nap.

But I couldn’t nap.

It started to rain, and all the flamingos were flocking toward me to not get wet. These domesticated flamingos are so tamed they hate to get wet. Flamingos bustled around the roof and their feathers were everywhere. And their terrible warm scents as well.

I don’t know exactly why but I got infuriated all of a sudden.

I grabbed one of the flamingo’s necks and walked towards the forest, to the End of the World. I held its beak tight so that it could not make a sound. I don’t remember how I felt when I was walking across the rye field and walking down the forest, to the pond at the End of the World. When I finally got there, I pressed the flamingo down into the water and snapped its neck with a pocketknife.

It only took seconds for the water to get completely red. Red water flowed down to the edge and fell into the endless darkness.

I completely ignored Dad when he asked me if I saw Patrick, and ignored my duty to water the flamingos and went straight to my room. I knew Dad would be looking at my back, with his sad looking eyes, just waiting for me until I said something to him, wearing his pastel-toned shirt. I knew so well how fragile he would look, which was so unbearable to think about, so I pushed his image out of my mind and walked up the stairs and slammed the door.

I dreamed the same dream again, my sight blinded with pink, but this time when it covered my sight it started to turn red. And there was the dead flamingo.

When I got up in the morning I found the bucket was already in the garden and the flamingos had had an earlier drink. I knew it was Dad. I could imagine so clearly in my head, gently scooping up the water and pouring it slowly into the water bowl, waiting until the mingos would come to drink. And he would call their names whenever they arrived. I chose to get out, downtown, instead of doing my work, so I rode my bicycle down the street.

A market was going on. I stopped pedaling and let the wheel spin by itself, all charged by my exercise. I glided through the main street and watched a guy devouring a cherry pie. The cherry curd was all over his face and his hands, a fluorescent, artificial red that seemed to beam light. I fixed my eyes on him and watched him as long as possible as the bike was dragging me on. I briefly thought of my hands and the hand knife but the change of scenery pushed the thought out of my mind. There were hat makers, florists, potters, farmers selling fruits and vegetables, embroiderers each at their own booth selling their stuffs. Their livelihood was all in the air and I saw them talking, laughing, being surprised, frowning, living. All their livelihood altogether sounded like a giant buzz, and I was sitting on a bike, the wheels rolling down, and it felt hot and surreal. I passed a booth, another booth, and another til the end of the market booths, and then I passed by several houses and buildings. When the bike hit the dead end of the pavement it rolled down the lawn a bit and slowed. I got off the bike. It was the lawn nearby the apple farm. There was a water bucket with clean water. Seeing it made me realize that it was hot and I was sweating. My feet walked toward the water, and my whole body was gravitating towards the water, screaming for hydration from the inside. I stuck my face into the water and the water splattered. My face cooled down and the water seeped in between my curly hair, cooling down my scalp. I noticed that there were apples in the water. Maybe it was for washing the apples. I took out my face out of the water. A group of guys carrying a box full of apples that they had just harvested were walking towards me. Soon they poured them in the water. One of them turned on the hose and poured more water in the bucket and drank out of it too. I moved a little bit to the side of the water bucket. A boy, who seemed to be in his early 20s, came closer to the bucket I stood by and stuck his face right into the water. His shoulders shined with sweat from the farm work. I stared at his shoulders. I turned my face as he lifted his face out of the water. I saw him with my peripheral vision. With his teeth he grabbed one of the apples floating around as he lifted up his face. His dark wet hair shined. The apple was red, without a speckle of yellow. He looked in my direction so I looked down. Crisp, the sound of biting an apple. I was looking down at my sneakers, an old pair that hadn’t been washed, and I felt ashamed. I saw the shadow coming into the corner of my eyesight, slowly covering up my shoes with darkness. I looked up. The black-haired guy eating an apple was standing in front of me. He handed me an apple. It was just as red as his apple. And he returned to his group, back to work.

I rode back home as fast as I could. When I got back I went straight into my room, and took out the apple from my pocket. It was a perfectly red and symmetrical apple. I slowly pressed my teeth to the red apple, pressing down to its yellow flesh. Crisp, the apple cracked. It was a ripe apple, so sweet, almost too sweet. The sweaty shoulder, the black hair.

I dreamed a similar dream, but this time it started from the apple, which came so close to my sight and covered it up, and when it zoomed out, there was the dead flamingo’s neck.

I filled up the bucket, watered the plants and the flamingos, and raked their shits. I often dozed off to my delusions of the image of the apple, and the black hair, and the flamingo. I shook my head to get out of my distractions. I moved as much as possible not to think of the thing anymore, but the images returned to me over and over again. I raked hard on the ground.

And a hand landed on my shoulder, gently. I was startled and turned around. It was Dad. He was grinning as always with his soft colored T-shirt. “Get some rest, son,” he said. I realized that the ground was all ditched and bare. I walked back to the porch with Dad, sat on the table. Dad handed me a tea. And we were drinking tea in silence. His clear and soft blue eyes landed on me, always so sweet and gentle, but also penetrating. His eyes seemed to go through me and read any part of me, reading all my secrets, dreams and delusions. But he waited, as always, without asking, till I opened my mouth. He never forced. He sometimes cried when it was sunny. He would stop what he was working on and watch the sun. And teardrops would shine down his face.

I don’t know how he became a flamingo farmer nor do I know how he became a widower. I was afraid to know, so I never asked, and he wouldn’t tell me unless I asked.

I finished my tea and tried to leave the room, and heard Dad saying, “I will be here when you are ready to talk.” I stopped for a second, but without turning back I went out for work.

It started raining when I finished filling up the bucket. Flamingos headed towards the roof. I walked out to the garden, walking in the rain. I walked towards the field, towards the rose garden. I walked in, sat on a chair, watching roses in the rain. I wondered at how red it was, just like the apple, just like the flamingo blood. Would it be sweet like the apple? Or would it stink like the blood. I snapped a petal and put it in my mouth and chewed. It was bitter and sort of sweet, or maybe its sweet smell made me think it was sweet, or was it the rain that was sweet or bitter, I couldn’t tell.

I thought of the apple from the water bucket as he bit it up. The crisp sound of him biting. His dark black eyes, his hair dropping water. Red pond, where everything got so bloody, and the flamingo, so pink that it was pinker than pink. I closed my eyes. Rain hit my eyes. I faced the sky just like my dad faced the sun.

I had to go back to the End of the World.

I ran deeper and deeper into the woods towards the End of the World. To the pond. Water splashed as I stepped onto plants and I had some cuts on my legs from the leaves. I didn’t care. When I finally arrived to the pond, I saw the dead flamingo body on the pond bed. It was no longer pink. It was blue. I walked into the water and held it up. The body had lost all tension in the muscle and sagged towards the earth. I walked slowly back home, hugging the blue flamingo. I walked through the forest, through the rye field, the rose garden, and back to the farm. When I was walking down the hill to the farm I saw my dad holding an umbrella, waiting for me. I walked toward him, all wet and messy. I walked to him. “Dad, Patrick is here. I am so sorry.” He looked me in the eyes. I looked at his soft-colored eyes. “I am so sorry,” I repeated. He grabbed my shoulders. “It’s okay my son,” he said. “It’s okay.”

We walked to the back yard. Dad started to dig a hole. I left the body and helped him dig. We placed Patrick there, and buried him. Rain poured throughout the burial. I couldn’t tell the rain from the tears. We sat again in the porch, and Dad brought out a towel and wrapped it around me. And placed a warm mug with flower tea in my hand. And he sat across me. And as usual, he waited. I looked at his face for a while.

I opened my mouth. A word came out, and we talked for a long time.

The rain stopped and it was sunset, and the sky was pink, a pinker pink.

About the Author

Shantal Jeewon Kim was born and raised in South Korea. She is a writer, visual artist, and translator. She is interested in weird stories, the intersection of image and text, and possibilities and impossibilities of translation. She is currently an MFA Image Text candidate from Ithaca College.