SALT WATER

BY LAURA BRAVERMAN

Laura Braverman has woven herself a magic carpet. Embedded in its tapestry of mystery and transformation, Salt Water is a book of prayer, of faith, an ode to earth and life.

At times fairy-tale, at times requiem, Salt Water encompasses geography and identity to weave myths and history, music and tragedy, memory and literature. To quote Peruvian poet Américo Ferrari, there is here “an unspeakable where, perhaps, the nucleus of the living relation between the poem and the world resides.”

Water is omnipresent, and like Charon, the poet takes us on a journey to the underworld, but also back: “But you slipped into indigo under a desert / sky, suspended in the salt-water of the garden / pool—your last ocean swim, your final womb.” And later: “What did I—a girl floating / on her back, know of Tuscan Cypress? Tree of the / Underworld, of funeral wreaths. Tree of death, sorrow.”

We travel from a fairy-tale setting to death, and from illness to prayer and healing.

Laura Braverman expresses the alchemy of grace, allowing the work to become a spell.

Responding to the question, How does poetry help people to live their lives, W.S. Merwin answered, “The source that rises unbroken from the unsayable speaks to us of the impulse and mystery that we share with every living creature. The urge is meaningless, like the unknown itself, and in the end remains, by nature, unsayable.” To which Braverman counters: “No more everyday / of concrete things. Only darkness / pierced by spectral beams. Only /light moving towards / an unknown place. “

Poetry opens a window into the subconscious and allows us into another reality in ourselves. It opens and reconnects us to other dimensions within ourselves that remain closed to the conscious mind:

“Stay taken with the unreturned, / enthralled by the unmet—“ It awakens and nourishes the imagination. It is a door to the unknown, mysterious, unexpected, miraculous. It leaves us astonished, in awe, in the presence of the Divine and allows us to fully become ourselves: “If I could learn / the language of the unspoken, / decipher hidden burdens, I might / be seen in full: no more, / no less.”

At the heart of these beautiful, remarkable poems lies a quest to be fully alive. Sifting through geography and memory, Salt Water is a haunting tribute to family love and the human spirit to persevere in a broken world, a healing balm for the senses and the soul.

THE PATRON SAINT OF CAULIFLOWER

BY ELIZABETH COHEN

Elizabeth Cohen’s scrumptious collection The P#atron Saint of Cauliflower is a magical recipe for joy and a fully lived life. Both whimsical and practical, it enchants and reveals deeper truths. Like a benevolent fairy on earth, Cohen generously shares her spells: “The world is unraveling, but cabbage is steady.”

Later, “my mother taught me / how to crush a clove of garlic / with the heel of my hand / and watch the skin fall right off, / like a bride disrobing, her dress / left behind, in a heap of tulle.” “but it was green-black oval of the avocado / that showcased her best sorcery; / she could parse the contents with a single touch / and split one neatly, removing its heart / like the woodsman in Snow White / who had been instructed by the witch, / ‘bring me the heart.’”

She knows the redeeming power of beauty and grace and is not afraid to face devastation and tragedy. Cohen’s writing is elegant, powerful, unflinching. I particularly loved this beautiful, shamanic poem, “When I Was a Bird”, which is excerpted below:

I had the smallest bones

I could breaststroke on the smooth back of evening

I had no particular angerSometimes I made a meal of rain’s leftover wheat

I found certain beetles enticing

I loved fish…

After, I evolved into a mongoose

the smallest springbok of a large herd

a wildebeest, a Talaud flying foxbut I never forgot my ancestry

of feather and flock

What remains with the reader, long after the last page of this extraordinary collection has been turned, is Cohen’s lyrical wisdom, “the salty-leafed crush” of her love, a much needed balm for the soul.

FORGIVE THE BODY THIS FAILURE

BY BLAS FALCONER

Blas Falconer’s Forgive the Body This Failure is an intimate collection of bare, measured, yet lyrical and deeply moving poems.

It’s a meditation on loss, longing, desire, suffering, family and fatherhood, death, grief, emptiness, injustice, and finding clarity in what remains.

Falconer shares how our bodies fail and betray us, and how we betray ourselves, while searching for a way to keep living and building a life, carrying our failures.

He breathes a lot of spaces in these elegant poems, so our thoughts can expand. Silences mark the time. We experience immediacy and intimacy in communion. The despair the poet feels in how to respond to his son is conveyed through the distance and space carried in the lines:

I’m just a boy, you said,

but one day, I’ll die too,

and it became a mountainside,

the place your hand

pushed me away.

(Hiking at Dusk)

Geography, landscape, literal and metaphysical, are spaces to process what we’re trying to understand and let the answers come. Questions of identity are framed through a photographer’s lens. I love the immensity captured in the simple gestures. For this book is also a gesture of love: “Combing your hair / after a bath at night, this / is how I love you.” (Hiking at Dusk)

Falconer had often visited his grandmother in Puerto Rico. She had a deep impact and influence by sharing the poetry of Julia de Burgos and Juan Antonio Corretjer. I had the pleasure of hearing Blas read his poems and speak about how soothing going back to visit Puerto Rico (after grandmother passed away) was, because time felt suspended and there was a longing for this kind of simplicity. His mother was also at the reading, which was very touching. “Inflection Upon Your First Meeting” is a tribute to both her love and their shared love for his son:

We didn’t look at each other, we hadn’t, but as you read, I recalled how

you would speak sometimes with this tenderness, and how I

wouldn’t leave without first kissing you, so each departure felt less

like a betrayal.

In these poems about reclaiming the body, I found echoes of Dorianne Laux’s What We Carry. “This / is your share / of the world’s grief, what you must carry, and / which I cannot bear/ for you.” “Everyone / carried something.” And: “They disassembled the bed, emptied drawers, and left what they found no longer necessary or too heavy, or held a memory they’d rather not carry: the small deaths, for example, buried in the yard.”

We now know our intelligence resides in every cell of our body, not just in the brain. Our memories are stored in all our cells. “The way someone / exits a room and takes / everything with him. (Leave-taking)

This breathtaking collection serves as a map so we can come to terms with all these experiences and find some acceptance and solace. The body, a recurring image, is also a metaphor for what we fail to express in the moment. In that sense, Forgive the Body This Failure is very Jamesian in its resignation and surrender to what cannot be changed.

VACANT POSSESSION

BY ANNE FITZGERALD

Anne Fitzgerald’s recent collection Vacant Possession (Salmon Poetry) is exquisitely crafted, a beautiful, heartbreaking and haunting read, which begs revisiting time and again.

It opens with a stunning, hypnotic love poem which casts a spell and sets the tone, for this is, above else, a book about love. In poems about redemption and a love that transcends all, Fitzgerald works to reconcile the world she knew with the world she lives in. She writes about finding her compass, her mother, her identity.

When witnessing her mother’s death, she mourns, “When whiteness does hold / the world as I know it is no more.” … “a blizzard / of disbelief / whitens my / world as / I knew it.”

The triumph of Vacant Possession is that Fitzgerald, against all odds, deftly and with unparalleled grace, rediscovers and repossesses the lost parts of herself.

For this is poetry as shamanic work, soul retrieval, deep healing and testimony, as well as a searing indictment of a society where mothers and their children born out of wedlock have been prey at the hands of the Catholic Church.

Fitzgerald conducted astounding research. To quote her postscript,

“From engagement with various State and Church agencies together with research conducted I can confirm that Éire’s Architecture of Containment thrives in matters pertaining to the release of Adoption Records in Twenty-First Century Ireland. A trinity of control and culpability pervades within the Catholic Church, the Irish Free State and its Religious Institutions specifically established to contain, to profit from and to manage the lives of those who bore children outside marriage and the little lives born outside of the bands of holy matrimony.”

Both lyrical and precise, Vacant Possession stands as witness, a heartfelt tribute to her mother and to all who underwent such fates. This is a powerful and necessary collection on the human condition that everyone needs to read.

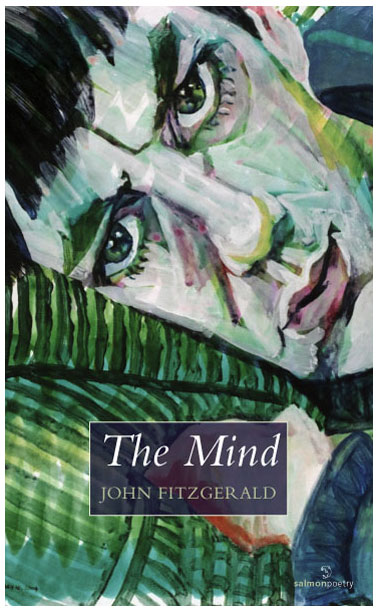

THE MIND

BY JOHN FITZGERALD

The Mind by John FitzGerald is a collection so profound, extraordinary, and almost unbearably beautiful, that I keep going back to it time and again to replenish spirit.

It is composed of eleven chapters, containing a series of parts made of nine lines each, divided into three tercets.

Its pattern is that of a circular labyrinth, which takes the reader to the heart or center of human consciousness through a series of nine philosophical journeys. At the beginning, the poet is “Removed From the Center,” then experiences “Fear,” “Time,” “Beauty and Truth,” “Death,” “I,” “Prophesy,” “Rules,” “Choice,” and “A Mind like the Wind,” before “Regaining the Center.”

This metaphysical labyrinth is a powerful meditation device, which not only brings solace but also transformation and healing. I could never be the same after reading The Mind.

In the opening poem, “One,” we begin our journey alone.

Pain is darkness.

You can tell when you close your eyes and it’s still there.

The thing that really disappears is light.

Removed from the center of the world,

I am alone, but that’s not the point.

There is no center as my life expands,

at least, not for more than an instant.

That is why time acts the way it does—

it knows the center is everywhere.

The poet makes several attempts in his journey. This spiral also embodies an ongoing, perpetual quest whose challenges are all-consuming. It also mirrors our universe – our Milky Way is known as a spiral galaxy – which is reflected in the mind.

Fear is one of the main protagonists in the story that keeps the poet from reaching the center. Yet, just like all the obstacles we need to overcome to become whole, it is also a door. “Fear has a face that disappears whenever I look into it. / Removed from the center of the world, / I am afraid, and that is the point. / Fear is a hole between two places. / Some might call it a door.”

And so, down the rabbit whole we go, as door after door is opened, and the poems call to one another in circular motion. The Mind delves into questions of identity, in particular sections “I” and “Time,” which map FitzGerald’s quest to know himself, to find his core. The existential question is posed here: “Here, where spaces / and lines intersect, is exactly where I should be. / Yet such measurements only serve to prove / that the mind doesn’t seem to exist.” In order to know oneself, one has to leave home.

Moreover, the Greek god of time Chronos and Zeus’ Titan father Kronos, are easily conflated: “Time’s father is the only one that begs for change. / He says maybe the only purpose for time is coincidence, / that’s how it recreates itself.” Time and death are intertwined. Even though only one section is titled Death, its shadow lingers over the whole book, for it is a tribute to the poet’s father, who died when he was only eighteen.

Coming to terms with his father’s death, FitzGerald explores loss and grief in a writing that is concise, rigorous, and so exquisite it takes your breath away. Berryman’s influence on FitzGerald is undeniable. He too was haunted by his father’s death. From “Dream Song #143”:

I’ll sing you now a song

the like of which may bring your heart to break:

he’s gone! and we don’t know where.

….

That mad drive wiped out my childhood. I put him down

while all the same on forty years I love him

stashed in Oklahoma

The presence of Rilke’s ghost too can be felt. As the poet travels in time, between darkness and light, and faces death, he can “But wonder whether demons manifest in body / fears that angels kept unconscious.” He is unafraid to follow his path into darkness, yet it is light he chooses: “If there is a reflection of light in an otherwise dark pool of water, / that’s the part I want to drink.”

And rebirth: “The mind shoots up out of the dust as if from nowhere” … “and restart the whole process anew.”

“Let us question each verse till it shows us.” This is the work of a master about the process of writing, “Rule three is write what the mind provides.” FitzGerald is a keen observer par excellence, whose expanded sense of time and sheer joy in creativity are combined with intense wonder. He is analytical yet emotions run high.

The Mind is a remarkable, elegant collection of transcendental, primal beauty by a formidable poet, whose work never ceases to astound.