Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

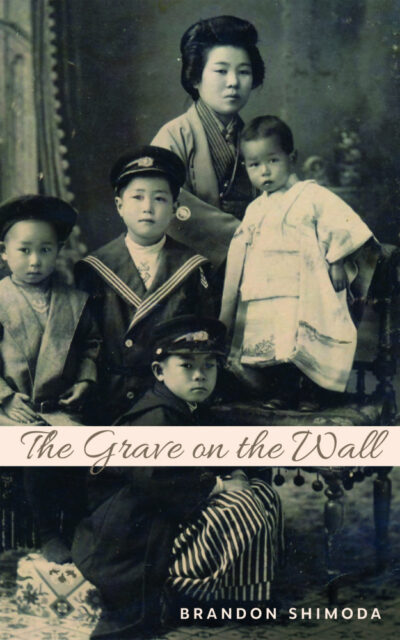

The Grave on the Wall by Brandon Shimoda

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Tarpaulin Sky interviews Brandon Shimoda, author of The Grave on the Wall.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

The Grave on the Wall by Brandon Shimoda

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Tarpaulin Sky interviews Brandon Shimoda, author of The Grave on the Wall.

When an elegy is an invitation, then we enter Brandon Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall (City Lights Books, 2019). This book invites a reader to haunt his memories and to excavate their gaps. Steeped in impressions and concrete memorials, myths and remembered conversations, this hybrid memoir traverses over a hundred years of family history, crisscrossing the ocean between Japan and America many times to inhabit the question, “When will I be most myself? Will I ever be?” (20). Alongside the narrator, the reader learns how to visit with grief. Centering on his grandfather Midori’s life, these essays use family portraits as a map to tenderly unearth forgotten graves and document America’s treatment of Japanese people through three generations. If rituals can provide relief, then could a photograph hanging on a wall in Fort Missoula’s Department of Justice prison be a tonic for a long history of silencing? Ritual itself is an evolving performance. In Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall, it presents itself as a children’s comic book about the atomic bomb; or breathing deeply into the camphor trees; or hearing the language dead relatives spoke. Shimoda teaches us not to build a fort inside one’s family tree but to investigate the roots, to trace a branch, a laceration in the trunk to the moment when relatives grow closer as well as to the purposeful and violent erasure of his immigrant family. From Hiroshima’s Domanju to New York’s Reflecting Absence, in documenting what has been memorialized Shimoda also reveals the gaping absences that memorials create – gaps that allow further haunting, that enable the United States to take in the scope of necessary reckonings.

Brief excerpt:

In what tradition is the washing of the feet a prerequisite to the journey, on foot, of the dead into the afterlife? Midori’s grandfather’s footprints would gradually be swept from the house. Would the aura come back? His grandfather’s face reared up like a pale pink fish, then evaporated. Midori was left with the image of cotton balls sticking out of his grandfather’s nostrils, his ears. He was sealed, could neither hear nor breath. Midori felt like that too, tried to shake it away.

To say that a village is on the edge of extinction is to say that its future us strictly memorial. That the village’s inhabitants are few in number and decreasing, without likelihood or possibility, even, of being succeeded. Maybe it is a diagnosis that makes it easier to colonize a living place with the presumptive and proprietary desires of the imagination. (16)

***

AH & JC: This book conjures myriad forms of water and the reader begins to know your different family members through their relationships to these various bodies of water. Oceans are crisscrossed by multiple generations, journeys that carry moods ranging from hopeful to resigned. For your grandmother, June, irrigation ditches are a formidable source that’s both life-taking and life-saving. We meet your grandfather, Midori, through his earliest memory of washing his own deceased grandfather’s feet in Hiroshima. His consciousness comes into being through this act. Do you have an early memory related to water that’s formative to you as well? Or an early obsession with a certain body of water?

BS: I fell over a waterfall once. Nantahala River, North Carolina, 1980s, although I’ve always remembered the river as having been in Tennessee. Maybe I fell (or was launched) from North Carolina into Tennessee. 1980s: I was young. My sister and I were visiting our aunt, who was (still is) a professional kayaker. She took us kayaking down the Nantahala River. At some point, I floated away from my sister and aunt, and got sucked into the current of a waterfall. I probably fought against the current, but was ultimately too weak to doing anything about it. I went over. I flew! And fell out of the kayak. I landed at the base of the waterfall, and got sucked into, then stuck in, the tumbler (or whatever it’s called), between rocks. Like being stuck in a washing machine? I don’t know; I’ve never been stuck in a washing machine. Like being stuck in, and constantly pummeled by, a wave. I remember daylight. I remember day. They became further and further away. Like I was being withdrawn from the world.

Then suddenly a shadow appeared on the faraway world, and from out of the shadow appeared my aunt’s hand; she pulled me out, dragged me out of the river, to shore. Similar (maybe) to how my grandmother rescued her brother from the irrigation ditch in Utah. So it’s a family tradition. A hand reaching down from another world, the world that once seemed to offer protection, but proved, instead, to be what needed protecting from. Then what was the hand? From what was it reaching? Was the hand asking to be taken, to be drawn, with me (or with my great-uncle) into the water?

I remember mud and tree roots. I was in shock, and shivering, for the next several hours. Into night. I remember sitting on a small patio of a house in the woods, wrapped in a towel, and staring at the patio light. A lozenge shaped light, mounted on the wall beside a glass door. As I was staring at the light, an enormous moth—the most enormous moth I had ever seen—landed on the light, and enclosed it (the light) in its enormous wings. I remember being terrified, and unable to move. I thought that if I got up or tried to escape, the moth would reach out and enclose me too in its enormous wings, and that I would, against the light, catch on fire, and burn very quickly. Then, when my aunt and my sister came looking for me, they would find only the enormous moth, wrapped around the patio light, glowing.

But maybe my most formative memory of water is my grandmother’s most formative memories of water. Her memory of rescuing her brother from the irrigation ditch in Utah and of her other brother drowning in the same irrigation ditch in Utah (which I wrote about in The Grave on the Wall, as you mentioned). Her relationship to water became known to me when I became old enough to realize that the reason she refused to go with us into the water—any water, but especially the lake across the street from the house where my grandparents lived in semi-rural North Carolina, where my sister and I went swimming—was because her brother had died in an irrigation ditch. Then the irrigation ditch, which was also referred to as a pond, became radiant (began to radiate), and my grandmother’s memory became mine.

It was not until many years later that I learned that the irrigation ditch tried to claim a second of my grandmother’s brothers. I did not learn that from her though, but him: my great-uncle, Saburo, who died not long after he told me the story. I wonder why death was an easier story for my grandmother to tell than rescue, or salvation. Even now, the lasting impression, or imprint, of a shadow on the water is not as much that of my aunt’s rescuing hand, but the light-enclosing wings of the enormous—and enormously menacing—moth.

JC: I love your description of radiating into your grandmother’s memory. I have a small handful of my friends’ or parents’ memories that have impacted me so strongly I think about them more than my own, too. I live inside these memories, have been absorbed by them, and they’ve become mine through this process of emotional and imaginative osmosis.

AH: First off, “imaginative osmosis” is an amazing term. When I think about that kind of shared imagination or consciousness, I think this is the essence of a good relationship. What struck me to my core about this book is maybe something that seems mundane — how you know people in your family. How you had conversations with them and shared parts of your history. Your waterfall experience is another example of sharing a memory. I really loved the way you paralleled your experience with your family members — the reaching of a hand. How you have a memory related to your grandmother’s memory, parallels to her life and yours that create a bond that can only be built by knowing someone. Communicating with family is so important in feeling close. Is this the reason you use ghosts in your book (thinking of the early mention of seeing your grandfather’s ghost or when you identify yourself as the ghost during your pilgrimage to Oko)? Or, I guess I mean: What, to you, is the purpose of a ghost both in the book and for people?

BS: That is such an enormous question! Like all the walls of a room or a building falling backwards, so that inside becomes outside, outside inside, no difference, all open, all flooded with weather and light. Two days ago, a woman asked me if I believed in ghosts. Actually, this question has come up a lot recently, not always in relation to the book, or to anything I’ve written about ghosts; most of the people who have asked me this question are people who do not know I’m a writer. It must be that people are feeling an unexplainable pressure, are even being visited, but don’t want to admit it. This woman, for example, is the security officer at the library where I work. I don’t think she was asking because she really wanted to know whether or not I believed in ghosts, or what I thought about them, but because she wanted to tell me, adamantly, that she did not believe in ghosts (although I don’t know why; she brought it up). I turned to my coworker and said, “She must be haunted” (or something like that). Asking if I believe in ghosts is the same, to me, as asking if I believe in people or plants. I live in a world of people and plants. Their existence does not require my belief.

The Grave on the Wall is a book of people, plants, and ghosts (among other things). They are the book’s inhabitants, and are equal to each other. But maybe I write about ghosts in a way that I don’t write about people or plants. Maybe I write about them in a way that unintentionally stresses the question of belief. It’s not necessarily because ghosts inspire more speculative or theoretical writing, or the kind of writing that attempts to think through what ghosts are, and their nature (although there is all of that), but because I take people and plants for granted. (Someone could just as easily ask: Do you believe in plants? And someone else could just as easily ask: Do plants believe in ghosts?)

There’s an artist I like very much, Aisuke Kondo, who makes work (videos, photographs, performances, installations) about his great-grandfather, who was incarcerated in the Topaz (Utah) concentration camp during WWII. For one of his projects (The Past in the Present, 2017), he reenacts photographs of his great-grandfather, by taking pictures of himself standing in locations where his great-grandfather lived and spent time, mostly in San Francisco. I first saw these photographs in a presentation Kondo gave at the Poetry Center at San Francisco State University. Kondo is a friend of mine. We were presenting together. Looking at the pictures of Kondo standing in front of buildings and empty lots and palm trees, I thought, and felt: He’s the ghost! The great-grandson is the ghost! Then I realized: the dead do not haunt the living, the living haunt the dead. That is what a ghost is: the haunting of the dead by the living. Of course, it is neither so strict nor straight. But it is certainly how I felt—not only writing about my grandfather, and my ancestors, in The Grave on the Wall, but traveling to spend time with them and their graves. Though we were haunting each other, it was clear that I was haunting them. That I was going to great lengths—traveling great distances, and through innumerable membranes—to breathe on them, to let them know that I was breathing, by breathing on them.

One purpose of a ghost or ghosts in my book, or any book (maybe), is the book itself: to give the book a reason to exist. In other words, without a ghost or ghosts, the book, or any book, might not need to exist, or might not even be able to. The same could be true of people. But, to answer your question in a different way, or rather, to re-ask it: why would it feel or be important or necessary to breathe on our ancestors, or to let them know that we are breathing, by breathing on them? What is the purpose of haunting, whether it’s the living haunting the dead, the dead haunting the living, or each haunting each?

AH: I love framing haunting as an important act for humans. This makes haunting a human necessity. It is part of how our minds work. I can also see haunting being necessary for creativity if we think of humans as the ones who haunt, who need the dead to know we are still communing with them. I have been told by many people to get obsessed with something if I want to write about it. For you, what is the difference (is there one?) between an obsession and a human haunting as you describe it?

JC: Speaking of obsession, I also wondered: Was there a moment during your research when you felt like you had “enough” information? Is there ever enough? For example, one moment that struck me in your book was when you reached out to the archivist at the Center for Creative Photography about a pamphlet that contained your grandfather’s name, which was the only one listed with a question mark by it. You wrote, “That question mark spoke to me. It seemed to be mine, my question.” The archivist wasn’t sure if your grandfather existed or if his name was a pseudonym used by the photographer Midori apprenticed with. Once you verified that your grandfather did, in fact exist, you asked a follow up question to the archivist, requesting the name of the Japanese photographer who had suggested Midori was an alias. The archivist responded “the information is not accurate and not pertinent to your query.” That answer seemed so terse, callus, abrupt! I wondered about your emotional trajectory during this research. How do you shift from asking follow up questions to writing? Is there a certain level of mystery about each other you learn to live with? Did this process of gathering help you live haunting your relatives in any way?

BS: What is the difference between obsession and possession—between being obsessed and being possessed? Does one lead to the other? When you say human haunting, do you mean being haunted by a human (whether living or dead)? Because I often think or feel that the most inescapable form of haunting, or being haunted, is not by a human, but by what the human represents, has suffered, or has done. What the human has released into the world (the atmosphere, social space, groundwater, cellular life, psyche). Violence, for example. (I think and feel this acutely in relation to the United States as being a nation that is haunted—not only by the peoples and communities that have been, in its name, subjugated, dehumanized, and erased, but by the energy that proliferates as a consequence of systemic oppression and perversion. The United States is a nation both motivated and cursed by perpetual arrest (of every kind—physical, psychological), and in which hauntedness is synonymous with breathing.) If obsession and/or possession and/or hauntedness or being haunted are related to writing, then I would think that writing is, or could be, a form of exorcism. Which is hopeful, a forlorn hope.

Writing The Grave on the Wall, for example: it was, among many things, a way to exorcise the many thing that motivated it in the first place. Although, that makes it, and books in general (maybe), sound gastrointestinal. Maybe they are. When I first started writing The Grave on the Wall … Actually, before I started writing what would become The Grave on the Wall, I had “enough” information. I had more than “enough.” That was the place, the situation, from which I started. My notes were lists of information: names, place names, plant names, street names, names of the dead, death dates, birth dates, laws, acts, historical and biographical information, coincidences, and so on. The information enumerated delirium and despair; was weighing me down, and was weighing down the narrative possibilities, because all I could see, in the lists, was the arrangement and rearrangement of “enough” information, which was death on arrival (aesthetically speaking).

So then it became a matter of how to not only process and distill the information, but dispel and get rid of it, you know what I mean? It became a matter of laundering the information. That is what the writing became (or one of many things): a way to weave information into a form in which it could take on the second life of a nearly subliminal element within a more varied composition. (Is a book a Trojan horse? Depends on what is desired, in the dead of night, to leak out.) But, more importantly: my grandfather, my family, my ancestors, did not exist in the mass of “enough” information. Though the information related to their lives, as well as to Japanese American and Asian American history (among other subjects), they were absent from—or had been rendered incapacitated by—the information.

Sorry, I just got nauseous, and am feeling a little disoriented. It just came on.

I should probably erase that from my answer, but…

I don’t know how I shift from asking questions or follow-up questions to writing. I’m teaching a class right now on the poetics of postmemory at the Poetry Center, here in Tucson. The class is called About Our Ancestors. I have fifteen students, all of whom are writing to and alongside and with their ancestors. Their most recent assignment was to generate 30-50 questions that they would want to ask directly of their ancestors. They shared those questions last night. We went around the table, each person asking—speaking—one question at a time. Round and round and round, until it felt like the table was spinning, buoyed by the energy of each question, and the accumulation of all the questions.

The questions ranged from the mundane (“Did you eat rye bread?” “Who brushed your hair?”) to the speculative, even ethereal (“Did the trees sway when you walked by them?”) Many expressed a deep concern. All of them were heartbreaking. We realized that the act of asking questions was, in itself, an invocation of—and an invitation to—the dead. And that the questions summoned, especially by the poignant fact and force of them being thought of and articulated—then shared out loud (our class meets at night; the windows are black)—their own answers, therefore a dialogue. There was, in that moment, no distinction between asking questions and writing, and there was also no distinction between what was known and what remained unknowable. If that makes sense. If that is even possible….

JC: I wish I was taking your class, I’d love to hear ALL of the questions your students generated! I was thinking about how your book is dedicated to your great-great-grandmother Yumi Taguchi as well as to your daughter, Yumi Taguchi. As a new father, is there a ritual you have right now with your daughter that you’d be willing to share with us? Or one that’s meaningful to you that you hope to cultivate with your daughter as she grows?

BS: Yumi got two shots yesterday morning, one in each thigh. She was fine for the first few hours. Until the early afternoon. We went for a walk to the public library. When we got there, after I took her out of her stroller, she went straight to one of the computers (as she usually does), climbed the chair (which takes a minute), and started typing and playing with the mouse. She has a routine. Rehearsing work and play (we haven’t logged on to the computer yet; it’s just the screen saver), which is play, also work. Yesterday, after typing and playing with the mouse for a few minutes, she asked if I’d help her down from the chair, which she asks by staring at me and saying, Help. I helped her down. Back on the floor, she just stood there. I thought maybe she was going to the bathroom. She looked like she was lost in thought, had remembered something grave, and was momentarily possessed—seized—by what she remembered. Then I realized she couldn’t move. She was stuck. I picked her up and set her down a few feet away. She still didn’t move. When I tried to get her to walk, she started crying. That’s when I realized: the shots. She was in pain. Her legs were sore, which is not a sensation she’d experienced before. She was uncomfortable, confused, scared. I encouraged her to take a few steps. I put on one of the library’s animal puppets, a frog, and had the frog encourage her to take a few steps. She couldn’t, or didn’t want to. Too painful. Her legs were heavy.

I picked her up and sat with her on the library’s couch. I read her Ishta Mercurio’s Small World, which begins: When Nanda was born, the whole of the world was wrapped in the circle of her mother’s arms: safe, warm, small. But as she grew, the world grew, too. Then I put her in her stroller and we walked home. When we got home, she refused to let go of me. So I sat down on the bed, where she spent the next two hours lying on top of me, refusing to get off. It was like she was a newborn again, amphibious, which I relished, but I also felt bad for her. I called her mother (my partner, Dot Devota), I called her nurse, I sang her songs by Ella Jenkins and Pete Seeger and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, read a few pages in James Baldwin’s Just Above My Head, until she fell asleep, hopefully into a dream in which her legs were no longer sore. We walk to the public library at least once a week. We take, or try to take, a different route each time. It used to be that I would narrate the walk, calling out trees, flowers, cats, dogs, clouds, airplanes, buses, shadows, pieces of garbage. But now she narrates the walk as much as I do, pointing out the same things, but also new things, with her expanding vocabulary.

Because she is learning a language, her enthusiasm for knowing a word often outpaces her using the right word. More often than that, she responds, with her vocabulary, to the shape or the essence of a thing, as opposed to what a thing is. So, for example, she might see a tree and say elephant (or her word for elephant, which is a-funt). Maybe because the tree is shaped like an elephant or maybe because the tree reminds her of an elephant or maybe because the word that came to her mind in that moment—that was available in that moment—was a-funt, not tree. Or maybe something else. Or maybe all of the above. Or maybe she actually sees an elephant, not a tree, and that what I think is a tree, is an elephant. The trees and/or elephants eventually give way, on our walk, to the buildings of downtown Tucson, in the middle of which is the main branch of the public library.

But wait, before we get there, there’s one more place we visit. Outside the Children’s Museum, which is across the street from a park where houseless people congregate, is a xylophone. A public xylophone, which anyone can play. We often go to the xylophone. I play it for Yumi. It’s loud, and resounds; you can hear it from the street, you can hear it from across the street, you can hear it from all over the neighborhood. My favorite moment, which is also, I think, Yumi’s favorite moment—because it is the moment in which she breaks into the biggest smile—is when I run the mallets up and down the xylophone, which is called glissando, but which I call, because it feels like it: rainbow.