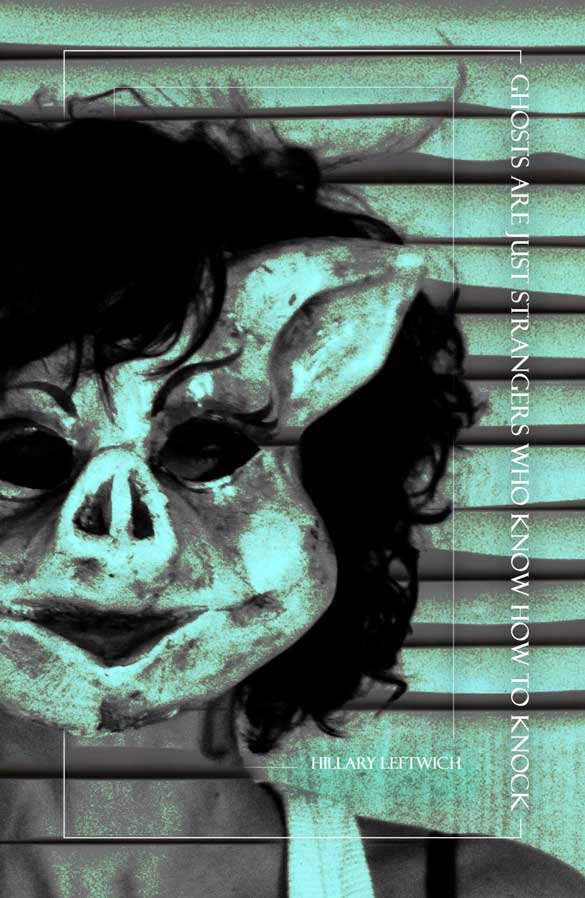

GHOSTS ARE JUST STRANGERS WHO KNOW HOW TO KNOCK

BY HILLARY LEFTWICH

For the late, great working-class artist Mike Kelley, trauma was a particulate reality. It was encoded in the battered plush forms retrieved from rummage sales that he strung into collages or arranged into bizarre pièces de théâtre. In Hillary Leftwich’s work, there is a similar encountering with the outré object, which places her alongside Shirley Jackson and more recent fabulists such as Brian Evenson and Sarah Rose Etter.

In “Somewhere There Is a Field Where the Birds Will Die for You,” the collection’s opening story, a man recognized from a photo asks to sleep in the speaker’s bed. How the speaker knows the man or whom he might resemble is not explained. But there is an intimacy expected that is not provided. When his body curls alongside the speaker’s, his skin is cold. When the speaker later awakens in a field of feathers, she is greeted by boys who claim to have shot the birds from the sky. The speaker remembers the coldness of the man’s skin when she left him in bed. What should be a relief becomes dread. The speaker knows no matter how far she goes the man from the photo will always find her.

A similar inevitability pervades “A Small Infestation Following A Big Stroke of Luck,” where a family that once subsisted on thumb-printed PB&J sandwiches wins a year’s supply of Doctor Pepper, only to fall victim to the undiscarded empties and the internecine conflict that erupts between the Regular and Diet varieties. The situation, which would not be out of place in an early John Waters film, never loses sight of social critique or plays its characters for laughs. As in the best satire, absurdity is treated as a point of departure. When the speaker narrowly escapes the swelling tide of empties by plunging through the bathroom window, we are left to wonder what was really in those bottles—and who had sent them.

A bear named Wilford Brimley, retrieved from a box from home, lords over the middle-of-the-night sleep of the speaker in “Ghosts,” shot glass in one paw, cigarette burned down to the filter in the other. The speaker claims not to remember the toy from childhood, but like the man from the opening piece, it is clear he remembers her. In “Road Kill,” the outré object is the endless stream of dildos uncoiling from motel sheets the Lyft-driving speaker remembers from her days as a maid. In “People Call You A Space Cowboy,” the object is a Jackson Five record stuck on “I’ll Be There” that suddenly begins playing the voice of its owner.

The collection’s title piece offers a key to these encounters. Rather than succumb to the jump-scare associated with horror material, the reader is instead directed to open that door. The stranger knocking is always the inevitability best faced with fists balled at our sides. Ghosts Are Just Strangers Who Know How to Knock announces the arrival of a talent that is able to manage both the atmosphere of repressed memory and totems of bitter socioeconomic reality. For single mothers and overclocked low-wage workers, Leftwich is the Lucia Berlin that never forgets to wear black.

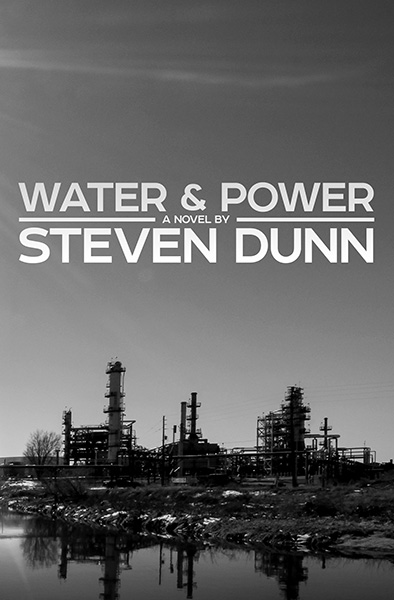

WATER & POWER

BY STEVEN DUNN

The title suggests a binary. But it doesn’t take more than a few pages to realize the book presents a continuum most of us have the luxury to ignore. The main character, called by a variety of names, is American Empire. The voices that flow through the pages never look the character in the eye. Instead, they speak of Empire’s deeds, its inefficiencies, its absurdities, and, ultimately, its human cost.

Water & Power is part-memoir, part-investigative essay, part visual poem. For readers looking for an easy entry-point, the best comparison I can offer is Studs Terkel’s Working by way of the twenty-four-hour, social media-driven newsfeed. Dunn curates a polyphony of voices, found text and imagery, alongside his own military experience. The result is an exploration of American Empire by the people who have sworn allegiance to maintain its defense.

Like Terkel, Dunn has spent a great deal of time with his subjects. They include military wives, soldiers from various places and socioeconomic circumstances, as well as of different gender and sexual identities. The subjects share horror stories, complain about lengthy deployments and always too-slow or inadequate benefits for their families. Most of these sections are less than a page, but through skillful editing, Dunn makes us feel like we know these people with the same intimacy as Terkel’s stockbrokers, cab drivers, secretaries, and other denizens of the Windy City.

Dunn is equally direct in presenting what life was like in the U.S. Navy. Water & Power follows him from recruitment, to training and deployment—all the way through to compiling the book. In one of the work’s most arresting passages, he wants a reader to know that, when asked, he tells people he “works” for the military; he doesn’t “serve” in it. The distinction is true to the character from West Virginia who is fully aware he is escaping one self-limiting system to become part of another. The author owns his choices throughout and presents his story with insight and humor, especially when characters from back home make periodic appearances.

The work’s greatest achievement, however, is the larger context that it strives toward. Dunn presents an historical view of recruiting posters and memos from ad agencies working for the U.S. military after the draft was outlawed in 1972, alongside anti-homosexuality training material, weapon’s specs, even lists of killed and wounded.

For anyone seeking a diligent and human look at the people whose immediate boss is American Empire, Water & Power is a book that deserves the broadest possible readership and the most direct attention among anyone studying the definitive art of this age of corporatized, non-stop military conflict.

ENTANGLEMENTS

BY RAE ARMANTROUT

“The Poem as a Field of Action” is a lecture William Carlos Williams gave at the University of Washington in 1948. The phrase, and the accompanying text, channel Einstein’s theory of relativity as a touchpoint for contemporary poetry’s “relativity of measure,” when approaching the line and form.

Entanglements, a 52-page chapbook from a few years ago, evolves Williams’ mandate for the age of quantum mechanics and string theory. Armantrout is never cleverer and more joyous than in this series of poems, inspired by her reading of Brian Greene and Nick Lane, among others. The delight is often overwhelming:

“God’s fractal

stammer

pleasures us

again.”

(from “Conclusion”)

There is a cohesion to this brief collection that is nonpareil. Entanglements delivers a perfect symmetry between form and content.

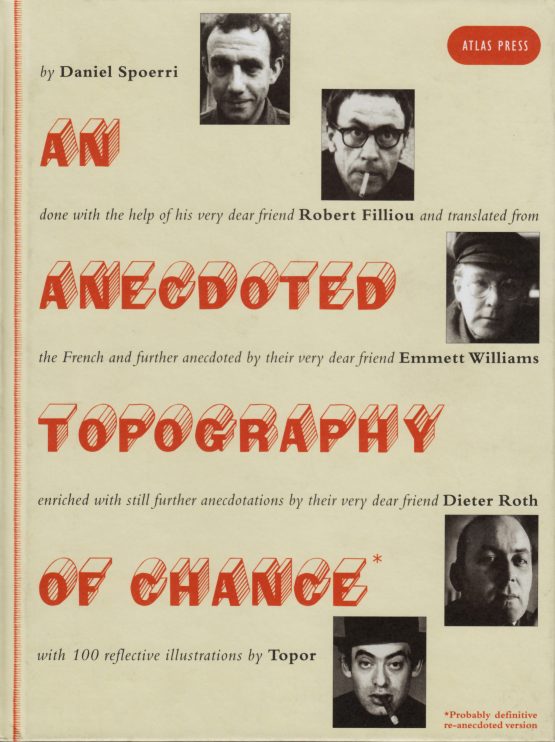

AN ANECDOTED TOPOGRAPHY OF CHANCE

BY DANIEL SPOERRI, ROBERT FILLIOU, EMMETT WILLIAMS, DIETER ROTH, ROLAND TOPOR

On October 17, 1961, at exactly 3:47 p.m., Daniel Spoerri drew a “map” of all the 80 items lying on the table of his room at the Hotel Carcassone, in Paris, where he was living at the time. The Swiss artist assigned a number to each object, and wrote brief descriptions, cataloging each item. The map and text were printed as a 53-page pamphlet promoting a one-man show of his “snare-pictures”—live captures of the contents of tables, preserved and displayed as vertical form. (Among the most famous “snare” works: the remains of a meal eaten by Marcel Duchamp, in 1964.)

As the legend goes, the pamphlet was such a hit that Spoerri teamed up with fellow artists Robert Filliou, Emmett Williams, Dieter Roth, and Roland Topor to expand the project. Filliou, Williams and Roth added notations; Topor did drawings of each object. The result is an informal history of a core group of artists, by way of detailed entries on cigarette lighters, crusts of bread, a plastic spoon, and other items. The entries cross-reference other entries, and the artists react to one another, as in a threaded conversation on social media. In the annotations for item 2, Pale-Green Egg Cup, Emmett Williams offers:

“d. How many eggs did KICHKA eat? In 1, the author states clearly that at noon KICHKA BATCHEFF ate a bit of white bread ‘with two soft-boiled eggs’ (avec deux oeufs à la coque). It was the slice of bread that she did not finish (mais elle ne l’a pa terminée)—singular—and not the deux oeufs—plural.”

An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, first published in English in 1966 by Something Else Press, is more than a clever approach to memoir and a fun look at a creative circle that would go on to influence Fluxus and other conceptual practices. The book, encountered in 2019, shows us a vital way to organize personal narrative that seems more in line with our non-linear, post-internet times.

Stephen van Dyck’s People I’ve Met From The Internet (Ricochet Editions, 2019), and Emmalea Russo’s Wave Archive (Book*hug Press, 2019) are two recent books that take a refreshing, indexed approach to emotions and physical history. An Anecdoted Topography of Chance is the clear precursor of such works, which access human reality in the pointillist fashion in which it is experienced. And, if I may be blunt, they ask more of us than writing of the “I-do-this, I-do-that” variety.

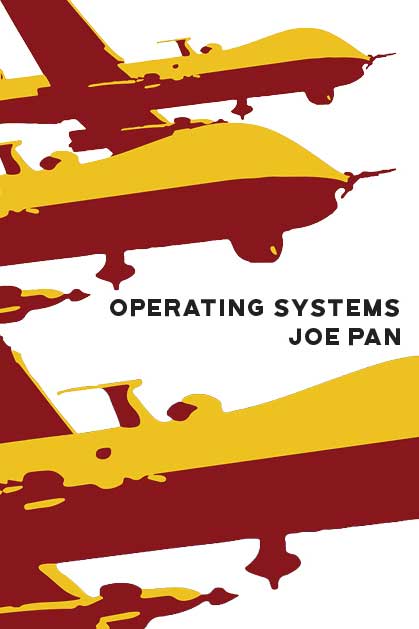

OPERATING SYSTEMS

BY JOE PAN

Skimming the pages of this book for the first time feels like one has discovered a guide for dismantling the American Empire. Like Dunn, Pan is concerned with the systems of meaning that power the status quo. But unlike Dunn, who focused on the people closest to the subject as victims, Pan’s attends the everyday tyranny and powerlessness many of us feel watching the news. In “Bedford Avenue L,” one of the collection’s opening poems, he writes:

“This is the moment I tell you you will be okay

& this is the moment you say no.

I do not know who I am telling this to.

I do not know myself at this moment,

& I do not know you. But hey buddy, hold on.”

These words arrive like a middle-of-the-night text message from a person unsure of everything except his own presence. Pan hopes this realization is enough to carry all of us past the current extremis in which we reside. There is an urgency in his gaze equal parts Whitmanian, equal parts tech-beleaguered 21st century global citizen. The opening of “Ethos” borrows more than a little from fellow Whitmanian Allen Ginsberg:

“America,

amore, I can’t

I know

survive you.”

But while Ginsberg contemplated the spiritual betrayal of the Cold War in “Howl” and “America” (which inspired the lines above), Pan evinces the same illness in the separation of people from each other by borders, both real and emotional. In “A Brother Returns,” an incarcerated brother is freed from the shame his crime is in any way unique:

“the lie we tell ourselves of learning

From previous mistakes,

When you & I both know we learn best by living out

Regret in utter self-

Deflating repetition, dry-docking our hopes to pills

Or some other intangible…”

Pan delves into the operating systems of Wall Street and the entertainment industry. But his greatest scorn—as well as his greatest feeling of resistance—arises from technology. “The Performance,” one of the most inspired and inspiring pieces in the collection, combines prepared text with tweets selected from the live stream that appeared during a live reading. At moments, the 140-character effusions are no better than Twitter on any given night, but from the selections in the book, the prompt seemed to guide the audience towards something beyond the tapping of fingers: a Whitmanian connection untrammeled by the particulars of identity, life history or circumstance.

The collection finds its greatest accomplishment, however, in the twenty-page poem that comprises the final section. “Ode to the MQ-9 Reaper” is an irregular ode, whose reflection on one of the deadliest drones in U.S. military history traces the same flightpath as Shelley’s “Skylark.” Pan’s attentive gaze examines every inch of the weapon with the same fierceness and dark humor Gregory Corso brought forth in “BOMB,” a calligram, or a shaped poem, from his third collection, The Happy Birthday of Death: “As an instrument sacrificing nothing of itself, you are a tool, Reaper—a dumb bucket of brimstones & nothing more.”

The call to sacrifice in the moment forms the core of Operation Systems. The sense of immediacy is realized in the closing sections of the ode, where the speaker seems to become the drone, applying its visual-targeting system to the proximate details of his life. The work closes with a quiet affirmation that absorbs the mission of the book’s epigraph, taken from Camus’ notebooks from the opening years of World War II: “Real generosity towards the future lies in giving all to the present.”