Syncope

BY ASIYA WADUD

In March 2011, 72 refugees fled Tripoli in an inflatable boat. After running out of fuel, it took 14 days for them to be rescued, despite the presence of 38 maritime vessels and a few governments who could have taken action, but didn’t. Instead, only 11 passengers survived. This story is the basis of Asiya Wadud’s heart-breaking long poem Syncope, told from a survivor’s point of view and which is both an indictment against those who did not act and a eulogy for the dead:

“We began as 72 ascendants

by that I mean we were a collective many

each bound for greatness merely

in the fact that we were each still living”

Wadud weaves into the poem fragments of language from the survivor’s accounts and reports about the left-to-die boat. A number of lines, such as “our bodies became deadweight” and “time is a heavenly host,” repeat throughout the text, drifting continuously toward the reader, circular in the way a boat might go, songlike in the way of elegies, shifting in meaning in the way of borders.

On the boat under the sun, Wadud’s speaker compares “the extremity of the / natural world / how unrelenting the / light / can be” with the extremity of racism and the violence of denying basic needs, that which allows the sun to kill. “We live with the wreckage,” is another line that repeats, written from the survivor’s point of view (“we are the ruin / meanwhile / we are not ruined”), and yet it is also those of us who are white who live with the wreckage of systemic racism that we’ve created, a wreckage that in this case took the lives of 61 people. Wadud’s poem reminds readers of the humanity we’ve lost, how our systems turned hope into something “rank” and “acerbic.”

The story of the left-to-die boat, the story of any group of bodies deemed not worth saving, is valuable both in calling those in power and privilege—and with opportunity—to act with justice and in giving voice to the voiceless. Syncope sings of a group of people who were once “luminous in that / we were each born under the / fabled light of some star” and grieves for the light gone dark.

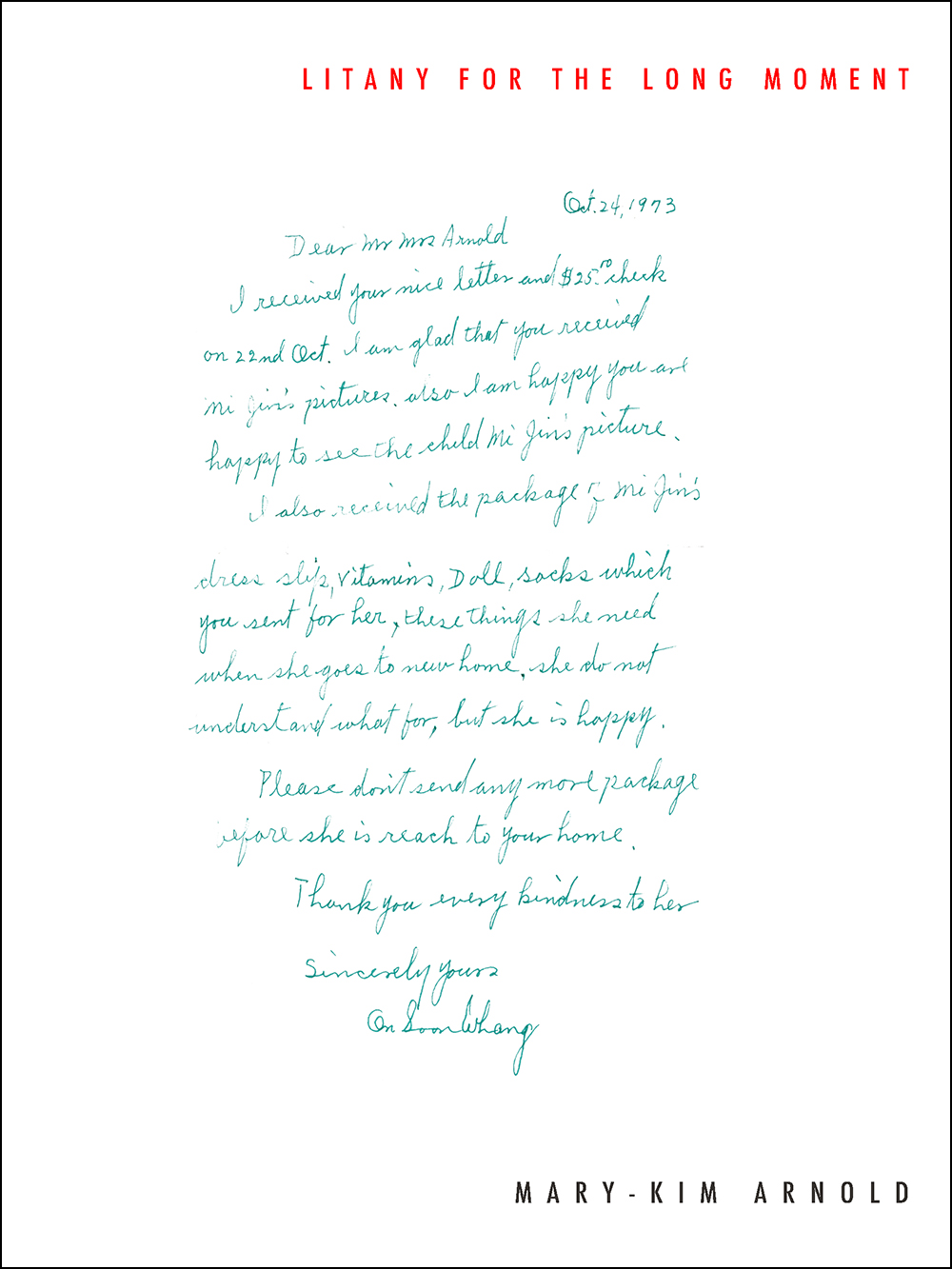

LITANY FOR THE LONG MOMENT

BY MARY-KIM ARNOLD

“The unspeakable orphan, defined by the lack of parents, can remain an orphan indefinitely, or become an “adoptee.” The transformation can occur only if action is taken by others.” After relying a long time on the actions of others, Mary-Kim Arnold’s Litany for the Long Moment is an attempt to claim her life as her own, reconciling the dual identities of Korean and Korean-American, as a child with two mothers and as a person who is working out what exactly the word “mother” means.

“I am struck by the difficulty of saying one thing, but wanting to say something else.

Something for which you don’t yet have language.

Something you may not yet know you want to say.”

Through her adoption documents, Korean-language learning guides, a handful of photographs, and a questionnaire from a Korean television program that attempts to reunite adoptees with their families, Arnold examines how language shapes us, what a mother is, and what it’s like to be of two countries at once and struggling to belong to either. In these explorations, Arnold attempts to take her life—that is to claim it.

In conversation with her muses Francesca Woodman and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Arnold considers how looking at a photograph is to be always arriving too late to a moment. “Holding fragments is not the same as making a broken thing whole,” she writes. And yet, making something is still an action. And even if not whole, even if still deprived of “some lost thing,” the fragments—and particularly her arrangement of them—do form a sense of self, an individual mind, a life irreducible to records.

1919

BY EVE L. EWING

In her second collection of poems, 1919, Eve Ewing writes in conversation with the 1922 report, The Negro in Chicago: A Study on Race Relations and a Race Riot, created in response to the 1919 race riots in an effort to understand its causes and prevent another riot from happening. Each piece begins with an excerpt from the report to which Ewing responds, using a mix of prose and poetry—including a haibun, erasure, and concrete poem—and a variety of voices—from a cleaning maid to schoolteacher-turned-stockyard worker—to recreate the spirit of the city that summer.

As in her first book, Electric Arches, Ewing frequently crafts her own folklore. The “Exodus” poems threading through the book echoes the biblical Exodus story, tracing the Great Migration up from the South, God’s disappointment in how his people have been welcomed into the city, and how the people thrive in God’s blessings while their oppressors suffer:

“And the people stretched forth their hands,

and there was a heavy darkness in all the city:

it weighed heavy on the heads of saint

and sinner alike. And the people smiled upon the darkness,

and the darkness was good. For upon them the darkness

was as burnt sugar: pleasing to the skin and sweet upon the lips.”

In “Jump/Rope,” Ewing relies on the language of jump rope rhymes—another type of mythmaking. Each time the rhyme approaches the subject of Eugene Williams’ drowning—that unspeakable grief and the catalyst to the riots—the poem interrupts itself, “no, it goes like—,” launching into another rhyme, another attempt to tell Eugene’s story.

Telling this portion of history in fragments allows Ewing to tell multiple experiences, moving from realism to the personification of a railway and streetcar, and to tie in current racial tensions. In “it wouldn’t take much,” she erasures a 2018 email from her apartment building on the day of the verdict for Jason Van Dyke, a white Chicago cop who fatally shot Laquan McDonald, a black teenager, in 2014: “Keep focus / keep your focus on the present / what is happening / before it escalates.” The words could have been written in 1919, a sad sign of what has not changed in 100 years. But I find Ewing to be a hopeful and visionary writer, and see this poem also as an urgent call for continued engagement and presence—with each other and with our city / our home.

SETTING THE WIRE: A MEMOIR OF POSTPARTUM PSYCHOSIS

BY SARAH C. TOWNSEND

Setting the Wire: A Memoir of Postpartum Psychosis by Sarah C. Townsend is a visceral portrait of how one moves through and in mental illness, a reflection on how we’re shaped, and the story of birth alongside loss of self. In fragments, Townsend shares the psychotic episode nearly twenty years ago which finds her, for a time, in an asylum after the birth of her daughter. “You cannot command memory. The mind has its own pace,” she writes, which is why, in returning to write about this experience, Townsend dips in and out of decades: her parents’ divorce (a container breaking) and her father’s mental illness, a moment with her second daughter sifting through family photos, her first daughter’s feedback on reading the manuscript about her birth.

Townsend’s patchwork of memories offers the perspective of hindsight but still feels immediate and intimate, always mindful of the people around her. “Mental illness is hard to tolerate, no matter what side you’re on,” Townsend writes with exhaustion and still—somehow—with empathy. It is a years-long process to heal, not only in piecing together her own sense of self again but also in trusting that her daughter, too, will be ok. “To say there is no impact . . . that seriously underestimates the significance of a mother, don’t you think?” asks her therapist. The only thing to do is trust that impact can be healed too, scarred over and evolving into something different, perhaps even a gift. Townsend’s questions of how to hold herself and those she loves in the face of loss will resonate with any reader.

GRIEF SEQUENCE

BY PRAGEETA SHARMA

In these sequences of short prose blocks, Pragreeta Sharma’s grief over the loss of her husband from a swift-acting cancer is palpable and heavy. Mixed in with the missing—the shock of being one day with a person and the next day without—is her memories of diagnosis, of the last months with her husband, hard days in which she realizes who her friends are and who are not, as well as memories of normalcy before diagnosis, what they did and wore and said to each other. Through it all, Sharma documents her feelings and mental state (“the only thing I can find to do is mourn my husband like a teenager, downcast, filled with careless intention, crying along a filament of sound in my Converse high-tops”) and tries to make sense of her new reality: “How gauche it is to be in this body being unseen by you now,” she writes. “You are not you anymore and I am trying to understand how a human with feelings has disappeared.”

Sequences, as in one thing chronologically following the next, can feel like a joke in the context of grief, in which memories blur together and time seems to stand still. “I’ve been sad and can’t find a seasonal sequence,” she says. In her sequences, she goes backward to the “creation myth” of her and husband or leans into routine. She tries to find a hook into this new life, a landing space within the grief. “My grieving turned into a sequence of writing,” she writes later. Each sequence an outpouring and then a break, a time to sit with and rest.

At some point the book opens up into the unique love letter that comes with bonding with someone new while still grieving. This is not like any other love poem—eager and rapturous, full of joy for the future. There’s confusion, surprise, fear that either beloved is diminished, and the work of learning how to hold two very different loves at once. It’s a sort of sequence, not time-based but another landing space. “This makes loving two people its own council. One followed the other, yet there is still simultaneity,” Sharma writes. The book continues in this vein, with the wonder for one presence and aching for another’s absence always entwined.

It’s hard to sit with and next to Sharma’s pain, particularly having been through a similar loss. The reactions and rawness of her process echo and converge and diverge from my own. When does one read such a book? When you’ve also lost a spouse or lost to cancer? To be in conversation with someone who has, with Sharma? Do you read for the sake of the living or to honor a body who was once here? Sharma writes, “Poetry and grief are the same: you are taught to care about it when it happens to you.” I don’t know who to recommend this book to, but it wrecked me. And I’m glad it’s here: as a monument, of sorts, to a specific togetherness and to a person. For the healing the writing brought. For the not-aloneness it gifts to certain readers.