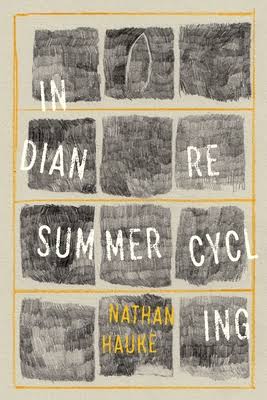

Nathan Hauke

Indian Summer Recycling

The Magnificent Field / Horse Less Press, 2019

Paperback, 84

Nathan Hauke’s Indian Summer Recycling, a collection of postmodern pastorals, evokes a singular sense of place. Front and center is the typically disregarded detritus of rural life—“hole-punched leaves” that linger beside “a greasy rototiller wed to wakefulness” (untitled); a “molted fawn” forages near “a wet black nexus of barbs below the trailer” (“Bands of strata”). Hauke takes the time to notice “Thistle that peels up out of the plaster of paris” (“Following a path/Into a copse/Of moss-scraped beeches/That’s been shot up with light”—yes, the poem’s title is lineated). Sequences of lines that read as tableaus, lists of noun clauses brimming with images, are essential to the collection’s poetics and emotional landscape. More and more things, natural and man-made, accumulate, and yet remain so apt in relation to one another that they do not overwhelm but establish and inhabit a space that feels wholly authentic, such as in “Red glass eye”:

A young mother picking lice out of her husband’s hair in Sunshine Coin-Op

Bubbles caught up underneath a shard of burned window

Chaw-weed layers the charred paper target

Mint and fried-out blackberries

Clusters of moths shuffling back into the tree line

The burned window and charred target in these lines suggest a story that remains untold, forgotten even, and the haunting sense of once-was-ness that permeates the pages of Indian Summer Recycling is essential to one of its primary themes: the decomposition that surrounds us and to which we are subject. In “Tinder is a hatchet job,” Hauke mentions a “Pink shred of ribbon tied to a branch near a deteriorating bottle cap/Where I piss into the brush.” While the ribbon and bottle cap might go unnoticed in our actual lives, these lines are integral to the way Hauke’s poems envision us deteriorating in a world that is constantly deteriorating around us. In his introduction to the anthology The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoral, Joshua Corey identifies as a trend in the postmodern pastoral “the task of negotiating local powers by mapping the permeable border between the self and the non-self, the I and its environment,” and while some poems in Indian Summer Recycling feel like they take up this task in their speaker’s imagistic focus on residing in a world of waste that accrues as a result of neglect, other poems view identity itself as also succumbing to decay.

For instance, characters in the poems, including the speaker’s dog (F) and spouse (K), are often referred to by only their first initials. X, who hung himself in the barn after he lost his family’s money, makes an appearance in a number of poems, and it is difficult to determine if X stands for a person’s name or if X represents a sort of crossing out of this person’s identity. Both interpretations feel correct. While the references to X feel elegiac, they also suggest the eventual anonymity to which death and decay lead (in “Shine an apple,” Hauke refers to a cemetery “Where family names are already/Worn off the stones”). That we don’t truly know who X is feels appropriate as we reflect on our own inevitable decomposition and as Hauke focuses not only on physical deterioration but also deterioration of thought, of memory.

Indeed, many of the spaces Hauke describes are those we might think of as tangential to our lives, as life having forgotten. And yet these poems brim with life in the unexpected places. Horse flies, mosquitoes, crickets, moths, black ants, bees, water racers, bluets, snails, a wasp drilling into the body of a cicada—the impact of these seemingly little lives is amplified as they interact with and among what humankind has disregarded—ribbon, paint, aluminum foil, scraps of fireworks, “what’s left of the chimney” (“Gunshots up the ridge”), the hidden kingdoms in which insects are the rulers, the portents and purveyors of the slow but unavoidable voyage toward decomposition. These poems call us to reflect on how our lives impact and are impacted by nature in ways we don’t typically think about, even as our attention and our memories are composted by a living, moving world, constantly recycling itself.

There is a bittersweet tension in inhabiting such spaces. On the one hand, there is the always-present sense that we are destined to decay, along with the rest of the world, which can be disconcerting. On the other hand, I think of the comfort to be found in the Buddhist concept of emptiness, of nothingness, in the interconnectedness of all things and the peace in the naturalness and inevitability of death. While reading this book I recalled the first poem in Stephen Berg’s translations of Ikkyū: “even before trees rocks I was nothing/when I’m dead nowhere I’ll be nothing.” While some of Hauke’s shorter poems feel akin to Zen poetry in their focus on the inescapability of passing, his vision of decomposition differs in that it is tinged with an air of danger, as in “Color is worse than eternity,” which I quote here in its entirety:

Ribbons of water shine like razor

Walking the dog with a mouthful of blackberries

Rain leaves mirror everywhere

Trying not to step in it

Thoreau: Our life is a forgetting

Where the bank of this shore erodes into current

This poem is also representative of Hauke’s poetics when it comes to simile and metaphor. His similes are wonderfully strange but always apt in the ways they reinforce the book’s sense of place. He sees “Bleached cans of Natty Ice in the grass/Slick as a dented swing set” (“Leaves where light carves your eyes”). But the figurative language is most thematically on point when it bridges the divide between the synthetic and the natural (as when the shine of water becomes like a razor). He describes “Standing slack-jawed/Breathless as a stomped pop can/Swarmed by gnats” (“As devil’s mischief/May produce beautiful gardens”). In “A dog wrings the neck for gladness,” “Dry leaves in grainy heat” are “startled like a toy duck with a shredded orange bill.” Like the burned window and charred target, this simile hints at a story, a life, destined to decay like fallen leaves. That such similes collapse the distance between the natural and the unnatural is thematically pertinent as all things become one through the process of decomposition.

Another tension in the book worth considering is that between postmodern formal choices and the lack of focus on more contemporary technologies: computers, cellular phones, etc. The technologies that do pop up—music boxes, toy pianos, staticky AM-tuned radios—have an antique quality that makes Hauke’s formal experimentation all the more striking. In “Wakefulness more like a stammer,” there are two different fonts. In the penultimate poem, the title is broken up so that it frames the first line. The book’s many caesuras come in a range of sizes. There are poems in which lines placed side-by-side have spacings that differ by a small fraction of an inch, almost simulating earthly strata, so that if one were to remove the white space between them they would exhibit textual overlay similar to a Susan Howe poem. Indian Summer Recycling is a collection in which postmodern formal sensibilities flourish in the absence of the technologies that gave rise to them, and this is a distinctive and exciting tension to dwell within. Despite these formal choices being highly constructed, their technological disparity from the rural settings they enrich can lend itself to the feeling that the language, like the world it describes, is broken, is breaking down. Hauke begins “If somebody don’t help me” as follows:

Language

s Torn

Weathered

Screen

Dewy

Mosquitoes

+++

Hatching

Tawny

Lamplight

Incomprehensible

As the smoldering husk

Of barn-

Hollowed dawn

The brokenness of language and Hauke’s formal moves magnify his collection’s focus on our place in a natural world that will eventually consume us. Breaking from its initial form and syntax, the poem fittingly ends with “Grief you can’t see the end of/Stray feathers unsettled along the periphery/The rest is decomposition.”

About the Author

James Henry Knippen is a poet who teaches in central New York. His work has appeared in 32 Poems, AGNI, Boston Review, The Cincinnati Review, Colorado Review, Crazyhorse, Denver Quarterly, Gulf Coast, The Kenyon Review Online, The Missouri Review Online, and West Branch, among other journals. He is the winner of a 92Y Discovery Prize and the poetry editor of Newfound.