June 7, 2020: If you had asked me what I was reading a week or two ago, it would have included some poetry translated from different languages, books from Asian American women authors, some Sherlock Holmes short stories, and a pregnancy book. But the events of the last couple of weeks called me to refocus my energy back to black authors, and in particular black women authors. It’s not that I never read black authors, but I wanted to dedicate my time—and this list—to the ones I’m reading now, who are helping me contextualize this particular moment (like so many moments before it) of black grief, rage, and joy. As a mixed-race non-black person of color, I will always have work to do to stand with black people in solidarity. Thank you to these authors for their generous offerings.

WE’RE ON: A JUNE JORDAN READER

EDITED BY CHRISTOPH KELLER AND JAN HELLER LEVI

I’d read many of June Jordan’s poems in the past few years or so, mostly just whatever is available online. I was excited to dive into this collection of her work, which includes letters, articles, essays, literary criticism, play excerpts, and poems. Getting to read all these different forms and sides of the writer results in a multi-textured experience; in this way, I learned so much about Jordan as a person through her own words, better than any biographers could portray her. The editors, Keller and Levi, briefly contextualize each section and the selections, cleanly bracketed so you know when they are writing versus when it’s Jordan’s words. I also appreciated the clarity showing when footnotes were included by Jordan herself and not the editors, for example. This mindful editing allowed me to hear June Jordan’s voice almost uninterrupted, but the editors’ additions are helpful and non-intrusive.

For instance, in their note to the selections from Passion: New Poems, 1977-1980, they reveal that Jordan’s dedication for this collection is to “everyone as scared as I used to be.” The poems contained in this collection are among Jordan’s most famous, including “Case in Point”, “Letter to the Local Police”, “Poem about Police Violence”, “Poem for South African Women”, and “Poem about My Rights”. These are poems that do not hold back, that are willing to bite and claw their way to unblinking truth. These are poems about rape, brutality, casual racism, and war, and speaking plainly about them:

Tell me something

what you think would happen if

everytime they kill a black boy

then we kill a cop

everytime they kill a black man

then we will a cop

you think the accident rate would lower

subsequently? (from “Poem about Police Violence”)

But Jordan doesn’t just reserve this voice for her adversaries; she directly addresses her friends too. In “A Short Note to My Very Critical and Well-Beloved Friends and Comrades”:

First they said I was too light

Then they said I was too dark…

…………………………………….

Then they said I was too angry

Then they said I was too idealistic

Then they said I was too confusing altogether:

Make up your mind! They said. Are you militant

or sweet? Are you vegetarian or meat? Are you straight

or are you gay?

And I said, Hey! It’s not about my mind.

These pieces are stark and uncompromising, refusing to play nice about the issues. I kept coming back to that dedication as I read these poems, and others elsewhere in this volume. To “everyone as scared as I used to be.” June Jordan did not come to courage through some innate superhuman unflinching character. She came to it through fear. Through facing the fear within herself. And that she dedicates her work to those who are still in a place of fear, unable to speak like she is. She allows her words to be the fire that light my own bravery.

EXPERIMENTS IN JOY

BY GABRIELLE CIVIL

Like her previous book Swallow the Fish, Gabrielle Civil utilizes a multigenre approach to archive performances, letters, interviews, book reviews, photographs, and more. So much of this book is about tracing collaboration and community, and reading it feels like an embrace in a warm ceremonial space. Civil begins in her introductory letter to the reader, “Preparation for ritual is ritual. / How shall we start this time?” She continues later: “This book is a lot. / Really, this book is a lot of people. / My friends, blood and chosen family, ancestors, artists, muses, students, and multiple versions of myself. / Still remembering.” It is in this beginning that as a reader, I am invited into Civil’s world of the body in performance, of many voices, of documentation, of a shifting archive of living practices. The book is peopled on every page, and I am invited into fellowship, quite literally, with all of them.

My favorite part of the book is “Call and Response”, which details how the title performance/festival/pieces came to be: Experiments in Joy. In her keynote address, “Experiments in Joy: Intersecting Blackness”, which she delivered in 2017, Civil writes: “I want to start here to suggest that we, in this moment, in this country, are at a crossroads. We have to decide who we are, who we want to be, what we are doing, and what we want to do. We have to bring that spirit of the crossroads into our body. / We have to be ready.” Reading this now, in June 2020, I know that we are still at this crossroads, that some of us have been preparing for this moment, while others have not. Some of us are ready, or have at least readied ourselves in some way. In the address, Civil leads a gathering of energy, from ancestors and from ground, to ready and to protect for this time in the crossroads. She writes that this is “our first experiment in joy.” Joy being a protective force in the land of the crossroads. Other forms of joy include telling the truth, making something new, and inviting someone in. I remember Duriel E. Harris—who like Civil was part of the original Call and Response project with other black women performers, out of which came the idea of Experiments in Joy—saying this in a talk at Naropa too: Tell the truth. Make something new. Invite someone in. Document. Repeat. Sources of joy that protect us at the crossroads. For me, it is this cultivation of friendship, friendship through creativity and honesty and joy, that offers the deep protection of the soul. That this friendship can be with contemporaries, with ancestors, with the earth.

I return to her opening letter to the reader, where Civil writes, “To claim joy at a moment of siege / may seem selfish or delusional at first….Black feminist joy does not disown awareness of systemic injustice. It does not deny oppression; it defies it.” These experiments in joy are as necessary as protesting in the streets, as reading anti-racist books, as donating and signing petitions, as having hard conversations with friends and family. Experiments in joy allow for imagination in the face of the unimaginable. And imagination is necessary when we are at a crossroads, to defy the status quo, to first envision and then manifest a new future: “So urgent and so lovely.”

NO DICTIONARY OF A LIVING TONGUE

BY DURIEL E. HARRIS

The first time I ever heard Duriel E. Harris read, I felt as though I had left my body while remaining glued to my chair, a spear driven through my sternum and pinning me to my place, while every nerve ending electrified and radiated out above my skin. This collection gives me that moment back. Harris is deeply committed to collective liberation, and exploring what this means within the body, through the medium of language. The book contains poems, prose, experiments with graphics and typography, sheet music, and even a broadside/folio tucked into the pages. This refusal to be restricted to a singular form is echoed in the language itself, as it moves between self to no-self to body to no-body:

I sit at the opening, listening, and bring the body into view || what I recognize as myself, a constellation of thought, disperses in abstraction

the way I hold my jaw, the way I hold my tongue, my bite, my grip

the way I hold my breath, my chin, my shoulders, my gait

remain

and beyond || a shingle of wind, lifted up

black birds descend from the trees like a flurry of ash (from “motionless or silent”)

In this collection, the body is ever-present, and yet dissolves into details of the landscape, through trees, birds, water, cows, wind, soil, smoke, and night. “The body is a phrase I repeat,” Harris writes in another piece, “Making”. The body comes back again and again in this collection, like waves ebbing and flowing, but never far. It is through this body that Harris allows us to access, as readers, concepts like sound and silence, speech, voice, and witness.

ROCK|SALT|STONE

BY ROSAMOND S. KING

I was first exposed to King’s work at the AWP 2019 conference in Portland, where she was on a panel entitled “Shape-Shifting Lineages: Conjuring the Feminine Divine, Power, and Creation.” And damn, did that panel deliver. For King’s portion, we wrote wishes in our notebook, and then crossed out the “I wish” parts, so that these statements stood on their own, a type of healing, she explained, that is possible through the rewriting of abusive, violent, or traumatic histories. For instance, mine were:

I wish my grandmother could have known love in her last days instead of bitterness.

I wish my mother could have seen and embraced her mother before she died.

I wish for the silence of my family to be broken open.

These became, through the alchemy of the page that King led us through:

My grandmother knew love in her last days.

My mother saw and embraced her mother before she died.

The silence of my family is broken open.

In this same way, King’s collection of Rock | Salt | Stone performs a transformation, as language plays and shifts, moves from spoken to unspoken to vocal again, and calling in new realities. Going beyond standard English, a cacophony of tongues rises out of the pages, unafraid of telling the truth and speaking new truths into existence. One of my favorite poems plays with Zora Neale Hurston’s quote, “I love myself when I am laughing, and then again when I am looking mean and impressive.” King gives us the laughter aurally, no longer just described but fully present, and remixes the quote into new meanings:

I love myself

when I am

he hee! ha ha ha whoooeeee!

………………………………………………………………

Watch out man be

cause

I love myself

I love myself

I love myself when I am

andthenagain

I love myself

When I am looking

These poems are so present, so immediate, that reading this book feels like getting to see King read them. That she is here with me in the room, laughing into my ear, or crying, or screaming, or shushing me, shushing me quietly to sleep, telling me to let my body stretch out, to sigh. The poems are spells, and I’m lucky to witness King conjure, cast, and shape-shift them into being.

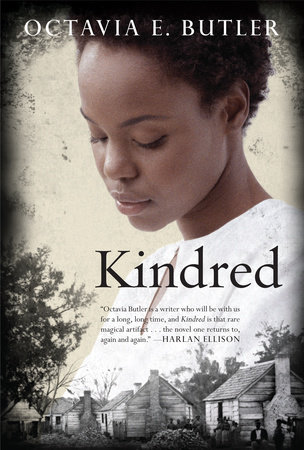

KINDRED

BY OCTAVIA E. BUTLER

I first read Kindred last spring, in March 2019, after my Cultural and Ethnic Literature students chose the book as one of our class readings (and I am eternally grateful for those students for that choice). I read it in two days, finishing a large chunk of it on a plane to California, which lent itself to moving back and forth through time, to limbo spaces, to impossibility. It seemed poignant to me to revisit this book now for the same reasons: how the present moment is in many ways a limbo state; it is ultimately a long-coming reckoning of the past, and a point of critical mass in order to break through into the new future, a future that seems impossible, but has to be possible, must be possible.

Butler wrote this novel in the 1970’s, and her protagonist, Dana, is a modern 1970’s black woman in an interracial relationship with a white man, where they have just moved into their new home together in California. Through unknown forces, she is transported back to the antebellum South, where she has to figure out why she has been called to this particular place and time before she can return home and stay there. Dana experiences the brutalities of slavery each time she is taken back through time, where she must keep the past alive. Though there are plot-driven reasons for this, I also find this book compelling to think about why the past must be kept alive now; even more interesting, Dana must also kill the past in order to survive.

I’m thinking about what it means to both keep the past alive—recognize the felt-reality (rather than the abstraction) of the violence of slavery, violence that we as a nation have never fully paid for, reconciled, repaired, or healed—and also to kill the past in the same moment. To kill the harmful actions and systems of the past, to kill the outdated practices and beliefs and hierarchies. Ultimately, Kindred for me examines the relationship of race and inheritance. What have we inherited, and what are our personal responsibilities with this inheritance? What gets reproduced through us, and what do we choose to not reproduce?

I’m being brought back to June Jordan now, too, thinking about what is possible in the making of what she calls The New World:

“[I]t means new; it means big; it means heterogeneous; it means unknown; it means free; it means an end to feudalism, caste, privilege, and the violence of power. It means wild in the sense that a tree growing away from the earth enacts a wild event.”

To get to this New World, this free world, this wild world, I believe that we must reckon with our inheritance, kill off that which we will no longer reproduce, and imagine a new inheritance into being, for all of our kin.