I have been calling this period of the pandemic and quarantine the Perma-pause, and in my isolation books are playing a central role. I think we all need to escape the bad news—disease, death, dissolution of democracy – and yet to escape entirely seems morally lax. What I read these days should open my mind to alternative ways out/beyond/around/under/over/through present difficulties. Some texts that have most recently challenged my complacency are listed below.

BESTIARY

BY DONIKA KELLY

It was the appearance of the poem “From the Catalogue of Cruelty” in the January issue of The New Yorker that made me aware of Donika Kelly’s brilliance. It sent me back to Bestiary, her first book, and to poems she’s published this year in Poetry, The Iowa Review, Taji, on poets.org, and in The Washington Square Review — poems that I imagine will be collected in her forthcoming The Renunciations. Look for it next year from Greywolf.

The particularity of Kelly’s work is that seductive combo of colloquial language – “this kangaroo is swole as fuck” (“A Poem to Remind Myself of the Natural Order of Things”) and scientific particularity. Which is not to say that her poetry is laden with Latinate words; the specificity with which she names things is laden with the weight of knowing:

I’ve been thinking about the anatomy

of the egg, about the two interior membranes,

the yolk held in place by the chalazae, gases

moving through the semipermeable shell.

This poem moves from the anatomy of the egg to the black bottle flies “drinking it clean,” and the metaphor of both lands a punch (or a punchline). The poems in Bestiary, named after medieval collections of morality-myths about animals, feature whales, gods, dogs, red birds, minotaurs, and “pollen and scales.” Some, like “How To Be Alone,” model her signature move, the fluid transformation of “I” to animal and back again, layering desire and shame and humor in a voice immediately recognizable. (Watch her repeat these moves in the remarkable “The Catalogue of Cruelty.”) In Bestiary, the poet works in couplets and triplets and the lines are often emphatically end-stopped, and yet, nevertheless, flexible. On poets.org, you can hear her read “I Never Figured How to Get Free,” a poem that begins (and ends) with a kind of logical subjectivity perfectly balanced in consonance:

The war was all over my hands.

I held the war and I watched them

die in high-definition. I could watch

anyone die, but I looked away. Still,

I wore the war on my back. I put it

on every morning. I walked the dogs

and they too wore the war.

Reading Kelly’s work, we, too, wear the wars of the domestic, personal, national, international. She shows us, reflexively, how we:

…never learned how

to get free. I never learned how

not to have anyone’s blood

on my own soft hands.

the book.

THE INVENTION OF MOREL

BY ADOLFO BIOY CASARES, TRANSLATED BY AST A. MOORE

Our hero, a young writer under threat of death for some unnamed political infraction, flees Venezuela for a deserted island where he finds some remnants of lost inhabitants – a mansion (called the Museum), a church, pool and tennis courts. One breathtakingly hot day, as he is lazing by the pool, a ship arrives bearing a throng of socialites. They are led by Morel, who seems to own the island. The hapless hero, fearful that he’ll be denounced to the police, withdraws to the marshes and rocks on the other side of the island where he scavenges roots and shellfish and spies upon the holiday-makers.

This odd little book is a prescient allegory for the life-sucking “semblances” of today’s screens and their effects upon our souls. Published in 1940 with illustrations by Norah Borges and an introduction by Jorge Borges – who called it “perfect” – it records the “adverse miracle” discovered by this fugitive who quotes Cicero, Malthus, and Valery.

Our hero soon falls for Faustina, a silent dark-haired beauty. He trails her to the rocks where she sits, contemplating the horizon, and he accosts her. She ignores him, seemingly looking right through him. His frustration and shame at her rejection gives way as he registers strange anomalies – guests shivering in cold on a blistering day, repetitions of overheard conversations, two suns in the sky. You guessed it: the visitors are projections, immortalized (and extinguished) by Morel in a process involving tidal hydraulics, mirrors, and 3-D photographs. It seems that, as Morel explains, “When all the senses are synchronized the soul emerges…” But are these “souls in motion” that the hero sees or are these human semblances who have lost their souls?

These “visual and acoustical” projections are precursors of “a more complete machine. One’s thought or feelings during life…will be like an alphabet with which the image will continue to comprehend all experience.” Morel continues: “Then life will be a repository for death.”

Sound familiar? Can we imagine which keywords will describe such “alphabets” of thoughts and feelings in the hierarchy of Google searches?

The Invention of Morel refracts our conceptions of consciousness. Is it the information of our senses, the way we move through time and space, or something ineluctable, something mysteriously like a projection of our minds upon the world? Read this and you’ll understand how this novella spawned “The Last Year at Marienbad,” “Man Facing Southeast,” and “Blow Up,” as well as the tv show “Lost.”

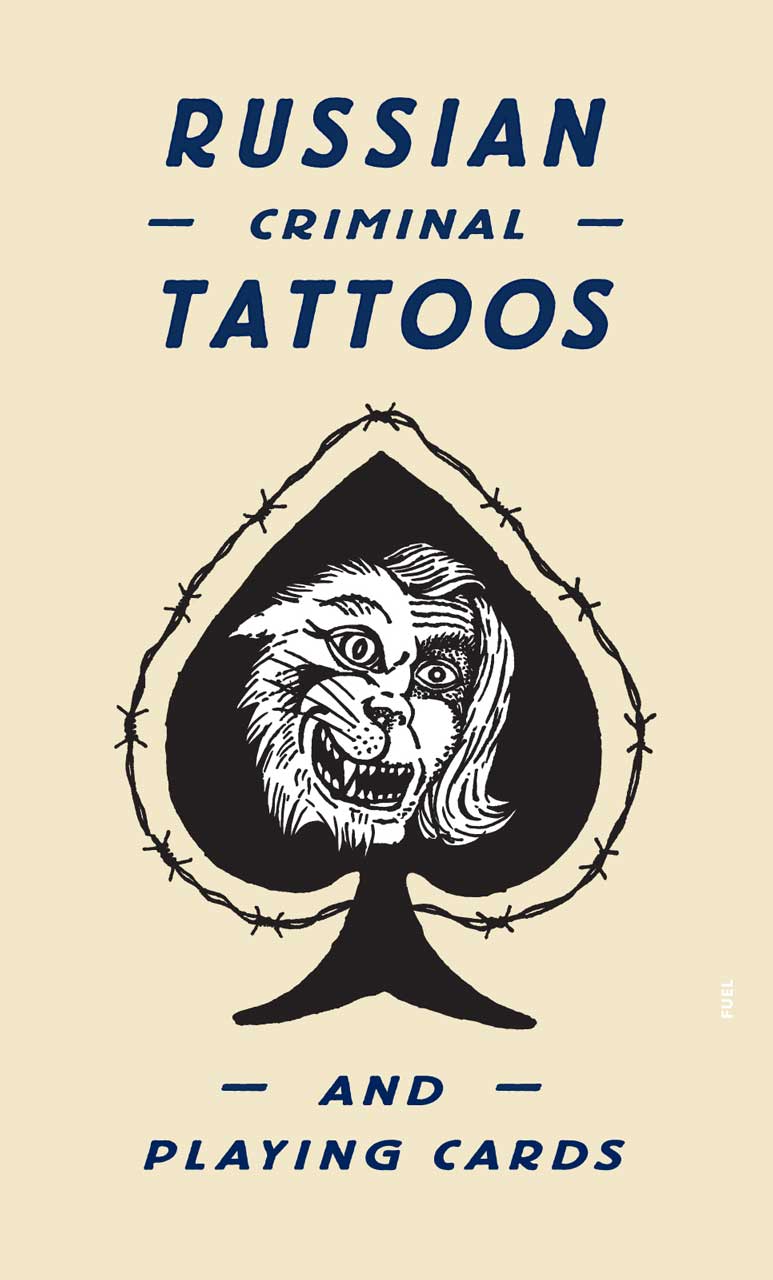

RUSSIAN CRIMINAL TATTOOS AND PLAYING CARDS

BY ANNIKY BRODOKOV

I discovered Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards, one in a series published by FUEL, in the bookstore of Berlin’s Hamburger-Bahnhof Museum. I was feeling bored by contemporary art — so ironical, so elliptical — and this gritty text, half anthology, half handbook, offered pleasures as shamefully voyeuristic as my grandmother’s well-thumbed True Detective magazine’s pulp accounts of hitchhikers and cocktail waitresses murdered and tossed into the long grass. (I remember scanning page after page of overexposed (presumably posed) photos of blondes lying prone, their eyes blacked by a violent rectangle of anonymity.)

I brought this book back to the States only to discover that it is highly popular here. Is this because it offers diagrams of a society where Might Equals Right and moujiks (real men) laugh at the weak and torment them mercilessly? Where the pecking order is ruthlessly enforced?

Could be.

Designed as a glossy take on samizdat, this book includes selected essays by criminologists, former convicts, and anthropologists who provide keys to the complex iconography of tattoos and homemade playing cards and card games fashioned in the archipelago of USSR prisons. In sleazily documentary photos, we delve into the iconography of tattoos that represent crimes, politics, vengeful wishes, and clans. Tattoos as autobiography, as war paint, as punishment. It’s a glimpse into a crazy world – indeed, more than a glimpse – of “the ruthless intracamp warfare between ‘bitches’ (those prisoners who worked with the authorities) and ‘honest thieves.’ If it sounds like Mad Max meets “The Penal Colony,” believe me it’s even more ruthless than Hollywood could imagine. Here, the taiga refers not only to the forests and plains of the Siberian arctic circle, but to the kill or be killed ethos of the “Zone” of correctional labor camps. Inmates are beaten ruthlessly by the guards for regime infractions; the inmates then, just as brutally, punish fellow convicts for any infraction of prisoners’ rules. (Certain iconic tattoos are forced upon prisoners who don’t pay their gambling debts and advertise their neprikasaemye or “untouchable” status.)

Here are photos of men and women modeling their tattoos of epaulets (etched on the shoulders to indicate an inmates’ “rank” in prison hierarchies), Wehrmacht mottos, naked women, and, surprisingly, chest-sized renderings inspired by the paintings of Giorgione, Bellini, Raphael, and Ingres. And then there are the prisoners’ faces: grinning, grimacing, dead-eyed, rapacious — even seductive.

Equally fascinating are the playing cards molded from paper, bread, and sugar, stenciled with the silver foil from cigarette packs and colored with blood and ink. The Perma-pause may even prompt me to make use of the patterns for making my own deck, including stenciled “suits” – and the ways to secretly mark the cards for cheating.

As we gamblers say, “read ‘em and weep.”

A TRADITION OF RUPTURE: SELECTED CRITICAL WRITINGS

BY ALEJANDRA PIZARNIK, TRANSLATED BY COLE HEINOWITZ

“In opposition to the feeling of exile, the feeling of perpetual longing, stands the poem—promised land. Every day my poems get shorter: little fires for the one who was lost in a strange land.” This is the voice of Argentinian poet Alejandra Pizarnik. Born in 1936 to Russian Jewish immigrants, she spent most of her adult life in Buenos Aires and in Paris within the circle of Octavio Paz, Julio Cortazar, and Silvina Ocampo. A prodigy, she published three volumes of poetry before she was twenty-three, and her influence and fame as a poet, according to biographer César Aira, had an “aura of almost legendary prestige.” (7)

Pizarnik committed suicide at 36, leaving behind a trove of poems, stories, and critical essays that have recently been translated and published in the States by New Directions and Ugly Duckling Presse. Here, in a selection of reviews, essays on craft, and interviews, her voice is singularly confident, her analysis subtle, and her commitment to craft absolute. A Tradition of Rupture – a phrase that lingers even beyond her discussion of poets who embodied a “rupture” with early 20th century poetic traditions — considers the artistry of Pessoa, Artaud, Cortazar, and Breton, among many others, and even reviews a collection of parodic detective stories by H. Bustos Domecq, the pseudonymous partnership of Jorge Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares (more on him below).

In self-interviews – a fabulous format! – Pizarnik writes: “I don’t believe contemporary society needs a reform. I believe it needs a radical change, and it is in this sense that benefits can redound to women.” (25). One wonders what kind of change she advocates, and how she would frame the “curse” of womanhood via her own experience: “…I assert that it is a curse to be born a woman, just as it is to be a Jew, to be poor, black, gay, a poet, Argentine, etc., etc. What matters, of course, is what we do with our curses.” (25). Pizarnik’s thinking on feminism and social justice demands further amplification and more historical context. How do we move from this to: “Among other things, I write so that what I’m afraid of doesn’t happen; so that what wounds me doesn’t exist; to ward off Evil…In this sense, the poetic task entails exorcism, invocation, and, beyond that, healing. “ (29)

I wish for a companion to this slim volume that could fill in the historical and biographical blanks – the context for such statements, and outline philosophical and emotional currents that underlie Pizarnik’s appreciation of Artaud, her critique of Breton, her assessment of Michaux. What kind of literary world – post 19th century – asks such questions as: “wouldn’t it be better to turn life into poetry than to make poetry into life?” The question is Octavio Paz’s and Pizarnik, responding, quotes herself:

I wish I could live solely in ecstasy, making the body of

the poem with my own body, rescuing every sentence

with my days and weeks, infusing the poem with my

breath insofar as every letter of every word has been

sacrificed in ceremonies of living.

This collection of prose, translated with a dynamic elegance by poet and scholar Cole Heinowitz, will send you on a pilgrimage to read Pizarnik’s poetry and trace the details of her life and times.