LEONARDO DA VINCI REDISCOVERED

BY CARMEN C. BAMBACH

I’m not a curator. I do not have what it takes. (I could barely even gather these five books.) My lack draws me to the curatorial imagination and genius of some of my friends, and to the work of art historians who have curatorial qualities, like the late David Rosand. Curators rule.

But my feeling of curator-worship is now literalized in me by this master work by Carmen Bambach. There is something divine about these volumes’ level of care and relentless interpretation. I grow impatient with attempts to efface the art historian as medium of the past, to re-create the past in some virtual form, to simply provide the archive in a digestible form as if archives could be naked or neutral or even digestible as the past.

Reading this volume, I’m swimming in the impossible complications, nuances, and foibles of Leonardo’s doings. But I am also swimming with the open difficulty, effort, and triumph of presenting these doings to us. Bambach has spent a long, long time cultivating the power, the faculty of insight, the advanced trainings that even make it possible to approach this task.

Leonardo might be famous for a lot of things, but among Renaissance art historians Leonardo is also famous for the fragmentation of his leavings, which began dispersing soon after his death. The beautiful thing about Bambach’s interpretation is that she shows Leonardo as a self-fragmenter, as someone whose willingness to plunge after his interests (and convince clients they should plunge, too) made for what I’d call a less neatly Neoplatonic genius package. This guy really was wild, even if he knew how to work the system.

I’m going to go ahead and give this book my highest praise. In my mind, Bambach’s book is also another part of the Renaissance. Not because it “reanimates,” “recreates,” or “re-enacts” Renaissance content. But because her interpretation is so careful and consistent that something like critical love appears, and makes history vibrate with eternity without attempting to merge the two.

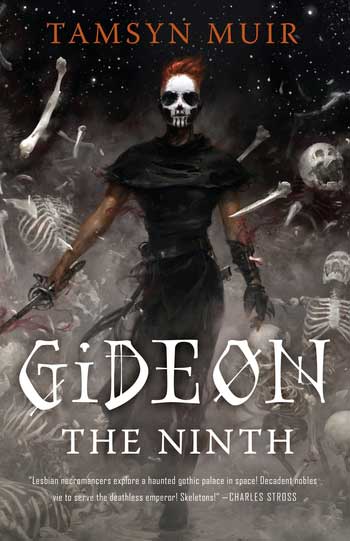

GIDEON THE NINTH

BY TAMSYN MUIR

There are some people who may stumble across this account of what I am reading who will mandatorily have to read this book. Someone named Charles Stross wrote, “Lesbian necromancers explore a haunted gothic palace in space!” This sentence should alert you to whether or not you are a mandatory reader. I will add that the complexity of the puzzles and intricacy with which they are described by Muir will please video game fans and techno-geeks, but not alienate you if you are not one (I have many of these people inside me, and not all of them like each other’s tastes).

Also, this book is seriously fucking funny. Great fourth-wall breaker, not a bad ham panderer. Maybe sometimes a good ham panderer.

I’m not sure the end of this first book is great in terms of contemporary thinking about healthy boundaries, but I guess I’m going to have to read the next one and then judge.

TO KILL THE FUTURE IN THE PRESENT

BY JENNIF(F)ER TAMAYO

I just found out in the process of trying to cite this properly that you can’t get it anymore. Sorry. That’s too bad for you.

This pamphlet, the third in Green Lantern Press’s “On Civil Disobedience” series, is so painful it is beautiful, but not in that straightforward, easily packaged way that white people want. My most recent approach to this text was to read the inserted Alien Change of Address cards from the Department of Homeland Security in the text. “Dear Baby,” the name field says. And other fields have other comments. What a play on address.

If your abuse is profound and beginning from infancy—am I talking to the US, or some imagined continuous entity “America,” or to someone too young to remember crossing that border? Or to, in a smaller but also true way, myself? JT, what if your next performance murdered those seventeenth-century personifications of America. Thanks for killing the future in that present.

A HISTORY OF ART HISTORY

BY CHRISTOPHER S. WOOD

It’s impossible to comment much publicly about one’s dissertation advisor’s immense new book. It gets even harder when that advisor has become a friend, and before that got you through some times so difficult you know that anything less than complete support would have meant you’d never have become an art historian—and then you’re reading that profound supporter’s idea of what art history is and has been.

I don’t think a lot of people I talk to will agree with a lot of the things in this book. It is cocksure about not having to address the concerns of Eurocentrism directly throughout (though there is very critically sophisticated attention to non-European art history in places). In general, the book brackets today. It says things like “man” when it means “humans” but in a kind of eternal human condition sense. Blech, why. Etc.

But I am going to go ahead and say that this book is beautiful, poignant, full of life. Anyone who cares about art history as a discipline with a history should read it, even if to disagree with it here and there. Disagreeing with good provocations has always gotten me somewhere, anyway.

How to describe the poignancy? Sometimes, when I am working with historical figures, they appear in my poems like dinner-party buddies, or at least that’s how I try to imagine them. But it’s hard to get that feel for people from the past. It doesn’t work with everyone.

Chris basically has that feeling for everyone (or at least almost everyone in this book, which is like, hundreds of people). The book is just on the edge of someone telling stories about other party guests to you while you’re at the same party, except the party has a subtle theme that you actually want to follow. You grasp the theme because the stories make you tear up a little, but in a kind of comfortable, social way. It turns out the theme is central to your life, and you can be chill about it.

Recently I made myself read the end of the book (you can go out of order). Here I agreed. I have to stop taking my encounter with art for granted. I have to stop hiding that encounter, even if to protect it from the frequent viciousness of peer review and other art historians. Those are not important. Saying implausible but elegant things here and there is not enough! Being honest about the poetics of my present sphere is not enough!

I have to let my actual art-world become part of my work, not just when it sneaks in, like when I wrote the last sentence of my first book, but more of the time, mindfully, letting the experience continue into my research and work. Because that’s the thing, good art history (as I said about Bambach above) extends the encounter. Playground peastone chalk on your hands, a little sweat, and laughter.

ON THE KEPEL FRUIT

BY TUNG-HUI HU

I wanted to give this chapbook to Chris as a present, and wrote to Brian Teare (whose The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven I was teaching at the time) to see if I could beg him to print more. Not anytime soon. Hui-Hui had just had a kid, and I still haven’t asked him whether he had more copies. I guess when the pandemic’s over I’ll make a pdf.

The reason why is that this chapbook is the most perfect thing I’ve ever read that I also loved. Helen Vendler once observed to us that a certain non-famous poem of Keats was a perfect poem. Like, ok, actually she was right, but . . . I don’t like that poem as much as I like the weirder ones, right? Does anyone?

I know I just promised to let my encounters enter my analyses, and where am I going to have the courage to do that if not here? Unfortunately, courage is irrelevant when the encounter is this strong. I’m still in the speechless zone.

How about this: this little thing is one of the smartest essays I’ve ever read, spanning economic history and sex anthropology and more. But it’s a gentle smart (you have to be super smart to achieve gentle smart imo). It folds you over and over like an expert baker. And navigating time is no problem, even though it is, in fact, the problem:

“We are a full season too early. People are giving me stories of kepel as if we were there moments after someone wearing a field of violets has passed through the room. I am just a little too late to see who or what caused the disturbance. I leave with these stories as if they were not the history of the fruit, but their sillage.”

Bring the sillage, friends.