In mid-May of this year, a writer friend of mine asked me if I had any advice to share with other writers during what can only be described as our intensely calamitous times. To my surprise, I immediately blurted out, “If you really want to make sense of what’s going on, then read more contemporary BIPOC authors, especially contemporary women BIPOC authors.” Well, having said it, I set out to practice what I preached. And I’m so glad that I did, because the universe responded by dragging me into the orbit of several books capable of not only capturing my splintering attention, but miraculously enough, also serving as a much-needed balm for the aches and wounds of a socially-isolating soul. In other words, to say that the pandemic has been difficult for an extrovert like myself is an understatement. But it was books, books such as the ones mentioned below, that have helped me to find both a spiritual and an aesthetic equilibrium (as if the two categories are mutually exclusive!). My hope is that by detailing what makes them so special, they’ll offer up something calming, inspiring, and/or creatively insightful to you, too. Without further explanation, here they are…

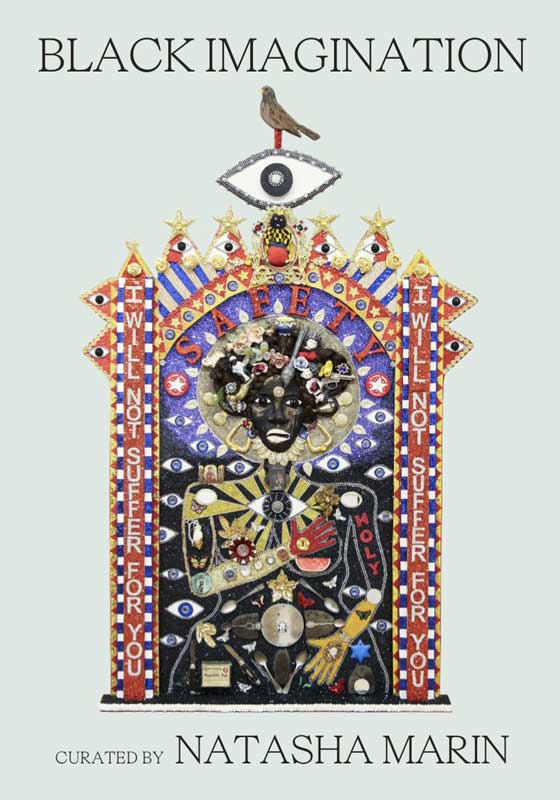

BLACK IMAGINATION: BLACK VOICES ON BLACK FUTURES

CURATED BY NATASHA MARIN

The first book I’d like to mention is Natasha Marin’s Black Imagination (McSweeney’s, 2020). This combination anthology/literary artifact/collection of testimonials is actually a companion piece to a sonic art exhibition meant to de-center whiteness as de-facto art and aesthetic practice that Marin put together in Seattle, WA with fellow collaborators Amber Flame, Rachael Ferguson, and Imani Sims. Thus, because the book consists of passages solicited and selected by Marin, instead of describing herself as the text’s author or editor, she simply lists her title as “curator.” And as a curator of text, Marin has done a bang-up job. She asked a variety of Black-identified individuals to answer three deceptively complex questions: “1) What is your origin story? 2) How do you heal yourself? and 3) Describe/imagine a world where you are loved, safe, and valued.” The responses she received are what make this book so refreshing and worthwhile. Marin went out of her way to collect evidence of all manner of Blackness—from the voices of Black youth to those of the incarcerated, the homeless, the neurodivergent, the differently-abled, and everything in between—and one of the many things that makes this book so notable is that it highlights those voices that tend to be marginalized when even Black folks commonly discuss contemporary Blackness between themselves.

All to say that this is not a greatest hits anthology featuring the names of all the Black writers you already know, and thank God for that. While the writing is at times, uneven, the collection as a whole is brilliant. There are pieces here that I found completely off-putting and juvenile, pieces that I hated, others that flabbergasted me, and still others that made me remember to breathe from my diaphragm because my perspective had been forever altered. In short, if one wants to seek evidence and understand Black intersectionality and all that it entails—culturally, emotionally, and especially aesthetically—then Black Imagination is incredibly rich, fertile source material. Given as much as it says and does, it’s a perfect book to include on a syllabus of nearly any level. Actually, I’m willing to go a step further and just say what I obviously feel: It’s a perfect book.

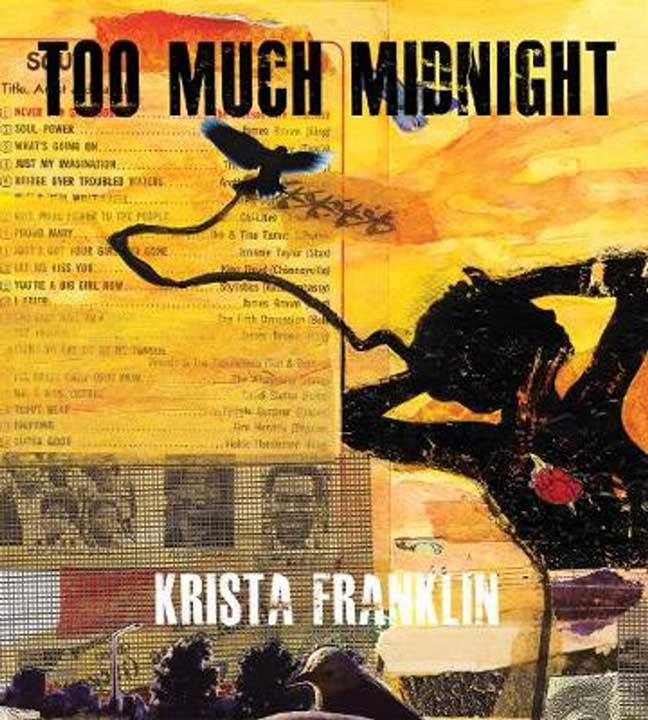

TOO MUCH MIDNIGHT

BY KRISTA FRANKLIN

However, there is earthly perfection and then there’s divine perfection. Author and visual artist Krista Franklin’s collection of poems and collages, titled Too Much Midnight (Haymarket Books, 2020), belongs to the latter category. Whereas Marin’s book highlights the ways in which the Black imagination often soars over impediments, Franklin’s work reminds us that in order to soar, there is nonetheless much personal and collective work that still needs to be done, down here on the ground. Yet that’s to be expected, because what makes Franklin’s work so impactful is that it’s fearless and visceral. It’s a visual and literal womanist intervention made to all of us; one that demands we let go of the little white lies we tell ourselves in order to get by/over/on/through/anything we want at all. Franklin spares no prisoners, herself included, and by doing so, exposes our desire to willfully ignore the moral discomforts and cognitive incongruities that confront us whenever we dismiss the fraught complications that arise from the intersection of race, class, and gender in our daily interactions and personal dynamics.

For example, take her poem titled “Alternate,” in which she writes of the other types of Krista Franklins that could be, but for a different set of circumstances and decisions. I only need to quote from one small section to illustrate how Franklin’s work can be equally as cutting as it can be illustrative of gender, race, and class dynamics: “Standing at the stove. 5 a.m. One wild-haired baby girl on hip. Pointing. ‘Skillet,’ she says. ‘Skillwet,’ she says. ‘Egg,’ she says. ‘Eg,’ she says. ‘Da-Da,’ she says. Prison, she thinks” (Franklin 56). Through the use of just a few pointed, precise words, including a contrasting verb, Franklin makes plain what countless sociological thinkpieces still fail to rightfully explain.

And that’s it, really, because after several readings of the poems in Too Much Midnight, I’ve come to a very logical, very simple conclusion. There are truly only two types of people in the world: Those who know of Franklin’s work and therefore stan for her every chance they get, and those who have not yet had the pleasure. Please do yourself a favor and join the former camp as soon as you can.

OF (WHAT PLACE MEANT)

BY KENNING JEAN-PAUL GARCIA

Speaking of language and precision, at another point on the creative spectrum we find Of (What Place Meant), by Kenning Jean-Paul Garcia (West Vine Press, 2020). Garcia’s book defies easy classification or description, but it’s nonetheless endlessly fascinating. Here is a (Diary? Novel? Some hybrid blend of the two?) solidly experimental work that functions as both a (pre)positional treatise on the self and an impassioned cri de coeur. One can see the influence of Pessoa, Proust, Stein, and oddly enough, Northrop Frye in this text’s pages, as it’s essentially a book-length meditation on what it means to define oneself in relation to the desire of others—or even worse, their antipathy and ambivalence. Of course, if philosophical flights into the nature of self and desire leave you cold, or linguistic jaunts into the myriad connotations of prepositional clauses isn’t exactly your cuppa, if it all strikes you as something akin to the opposite of pleasurable reading, then I’m here to tell you, fret not. Although not a poet, Garcia brings a poet’s sense, eye, and sensitivity to these pages, infusing them with so much lyric intensity and emotional weight that one often forgets the big ideas that run just underneath the surface.

All to say that this is a book best read in snippets and sections, so that one is able to take the time to mentally linger on Garcia’s carefully executed prose. Digest this text in brief passages consisting of only a handful of pages at a time and you won’t be disappointed. Of (What Place Meant) is both illustrative of and a testament to the act of literary (re)creation. It’s a book I’ll return to again and again, because each time, new disclosures, as well as new permutations and ways of reading it, will reveal themselves to me. And honestly, what’s better than a book that grows and changes along with you?

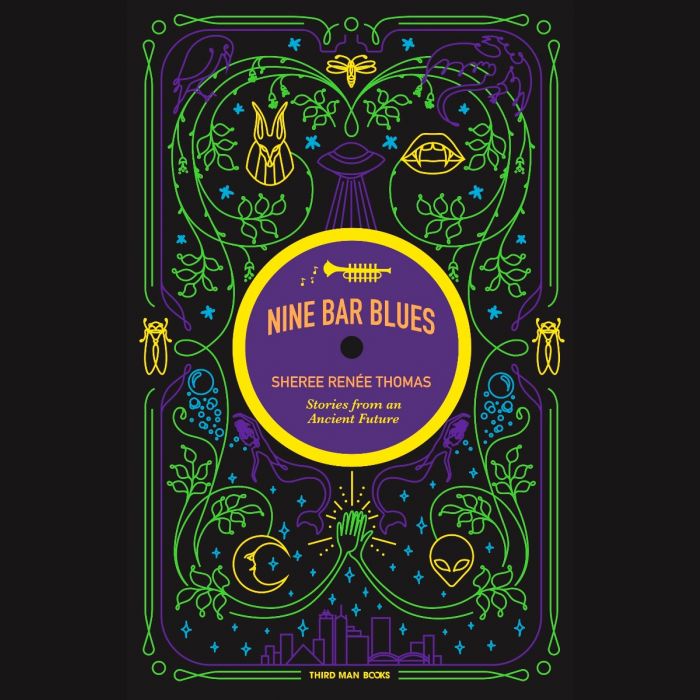

NINE BAR BLUES

BY SHEREE RENÉE THOMAS

But what sort of prose writer would I be if I didn’t mention at least one work of fiction? What has really been a joy to read is a short story collection titled Nine Bar Blues (Third Man Books, 2020) by Sheree Renée Thomas. Subtitled “Stories from an Ancient Future,” many would likely describe these tales as essentially Afrofuturist, but to label them as such is a bit too simplistic and reductive. While Thomas is indeed a major player among the Afrofuturism scene—her influential Dark Matter anthologies (Warner Books, 2000 and 2004) helped to define and jumpstart serious consideration of the genre, collecting many early practitioners and now-common names all in one place—the short stories in this collection do more than simply highlight our current love affair with all things science-fictional. No, in fact, many of the stories in this collection are more reminiscent of Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Gloria Naylor than they are of the Chip Delany/Octavia Butler variety (although they both get their due here, too). In short, what’s most remarkable about this collection is its careful blending of the magical, the fantastic, and the (sometimes secretly) spiritual to address contemporary Black issues, events, and concerns, without ever once seeming polemical or didactic. Really, perhaps the best comparison to make would be to say that if Toni Morrison and Kim Stanley Robinson had literary offspring, they’d appear a lot like the stories in this collection. Thomas’ work is as attuned to the material conditions that determine, define, and occasionally depress Black folks as Toni Cade Bambara’s fiction was back in her heyday, and with this book, Thomas has cemented her role as one of the literary figures whom we absolutely need to keep producing work, especially at this critically, culturally sensitive moment.

*

Sometimes the spirit moves me and I get relentless. Such as now, when in lieu of a fifth book I’d like to present instead a list of completely different titles with the addition of only the briefest of commentary. These are the books I selected in an alternate universe, but because I opted to spend my summer in this one, mostly reading Black women and nonbinary authors, I’ve had to make what the kids these days are calling “some choices” regarding which works to write about. Nonetheless, I highly recommend these additional/alternate texts for multiple reasons, the very least of which is that I’m already quite familiar with each author’s work, so I feel totally comfortable attesting to their excellence. They are as follows:

-

- Beauty, by Christina Chiu (2040 Books, 2020): Chiu’s award-winning, witty and fast-paced novel has garnered numerous accolades, including praise from such luminous literary figures as Michael Cunningham, Gish Jen, and Mat Johnson. Beauty tells the story of Amy Wong, an Asian American determined to be a fashion designer of no small renown, and traces the course of her life from hungry up-and-comer to unenthusiastic middle-aged adult—oh, and it also contains an almost encyclopedic amount of information on fashion and shoes. In many ways, it both perfectly mirrors and diffuses the anxieties common to many members of Generation X.

-

- M Archive, by Alexis Pauline Gumbs (Duke University Press, 2018): Not gonna lie, I haven’t read this one yet. But numerous people whom I carry a deep intellectual respect for have been clamoring me to read this for quite some time. Gumb’s book blends poetry, hardcore Black feminist theory, and post-dystopian science fiction together into a textual weave that I’m sure will leave me besotted. For those who love experiments in narrative and instances of just what the non-conventional novel can achieve, this book is for you.

-

- The Prettiest Star, by Carter Sickels (Hub City Press, 2020): This book has already generated a sizable amount of buzz as one of the LGBTQIA+ books to read this year, and I’m positive that its reputation is well deserved. Sickels’ novel concerns a young man with AIDS who returns back home to his small, arch-conservative Ohio town to die, and all of the scorn and derision he receives for doing so. It’s a powerfully affecting tale, capable of evoking empathy from even the most bigoted and hateful of readers. Please do check it out.

-

- Machine, by Susan Steinberg (Graywolf Press, 2019): I read this when it debuted last year, and all I have to say is that Steinberg’s novel is brutally raw, formally daring, brilliantly plotted, and so psychologically spot-on that I quickly joined the legion of readers who declared this to be an utter gem of a text. After reading it, you’ll ever think of an overprivileged mean girl in the same way. I can’t recommend it enough.

-

- Don’t Wait to Be Called, by Jacob Weber (Washington Writers’ Publishing House, 2017): A collection of short stories. Let the fact that Weber is the only cis, white male author to appear in this column serve as evidence that of all the fiction collections revolving around war and its aftermath that have come out recently, his is one of the very few well worth reading.

-

- And finally, a bonus text for the scholars and literary criticism lovers among us. Here’s a book I can’t wait to spend a great deal of time with: Afrofuturism Rising: The Literary Prehistory of a Movement (Ohio State University Press, 2019), by the always informative, incredibly insightful, Isiah Lavender III. Lavender works to establish the literary lineage of Afrofuturism here, as well as argue for its past, present, and continuing future relevance to not only Black contemporary literary production, but the whole of American arts and letters, making this is a text that I will likely repeatedly cite as essential, required reading.

So then, speaking of reading, thanks for doing so.