Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Jessica Q. Stark

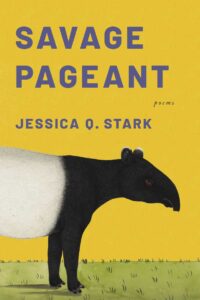

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Jessica Q. Stark, author of Savage Pageant.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Jessica Q. Stark

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Jessica Q. Stark, author of Savage Pageant.

Jessica Q. Stark’s Savage Pageant (Birds LLC, 2020) is the arm plunging into an archive box hefted up from a townsperson’s basement. In a book dedicated to survival – an act of preservation – poem and documentation, lyric and lineage entwine. Cartoon and narrative work like binary stars, enlivening one another. Bits of celebrity gossip, memories as single message board comments, forgotten injuries, and unexplainable disorders laid into poetry suddenly resist what Roland Barthes called “flat death.” While Barthes meant it as a term for viewing a photo of someone who has already died, this term, however, can also point to the stasis of anything archived. To write about history is to give it new motion, even if it carried on a stream. In Savage Pageant, it does not matter where the stream goes. It does not matter so much as remembering everything you saw as you followed.

Excerpt from Savage Pageant:

Miss Photoflash

for Jayne Mansfield

Where do you sleep tonight,

Vera Jayne Palmer?A heart-shaped pool,

a wayward corridor, a pink

penchant for gone-wrong.Working-class Monroe,

Blonde Ambition,Great Tail Switch,

Broadway’s Smartest Dumb.Attach a name to fix you

and keep you known.…(pg 44)

***

TS: You’re both an academic pursuing a PhD and a poet. A love of research – of information, really – is stitched within these poems. The information covers a wide array, from geologic information, historical happenings, biography of animal trainers, and even field notes in Thousand Oaks, CA. From the philosophy of Debord’s spectacle to the visceral and reflective experience of pregnancy. I see wheels at work. I love the way bits of information will gestate into a linear timeline, creating documentary-like piece, then this same information will resurface in more personal poems addressed to your son while you were pregnant. This type of recurrence happens in “Jungleland: A Genealogy, 1930-1951,” when a panicking elephant in a fire severs the theme park’s water main (pg 62), then appearing in “Savage Pageant: 33 Weeks” where you write:

Is it madness

to have you? Elephants breakingthe main water line. There are

things I’d like to tell you beforeyou are born: like don’t ever sit

in circles with strangers, likeyou don’t always have to be in

motion to survive, like the humanheart is capable of making the

head feel very small. (pg 80)

Information mutates and accrues. It is ingested or incorporated into a narrator’s body. This makes me curious about your relationship to research or reading from an early age. How do you remember reading as a child? Do you have memories of captivation with a particular subject that you kept coming back to – a desire to devour or immerse?

JQS: One of the most visceral feelings I have from a very young age was being in awe of my father’s collection of Encyclopedia Britannica; one of those five-shelf sprawling comprehensive collections that everyone inherited in the ’80s and ’90s from someone with little consent; those impressive-looking ornaments that took up a lot of space and nobody ever touched. I never, of course, read them cover to cover, but I loved the image of them. Their little illustrations done by some anonymous hand. I felt as if they contained all of the secrets of the universe, but nobody cared because they were boring and tedious. I remember flipping through them often at random, hoping to catch some hidden scintilla. I don’t know what. I don’t recall a single thing I read from those books. I wanted to be devoured by the bravado of encyclopedic knowledge and its shadow shapes; I was so convinced there was buried magic everything.

Did you know that Keith Richards from the Rolling Stones was reported to have broken ribs after a shelf in his library broke while he was reaching for a book, sending a full set of encyclopedias on top of him? Imagine being pummeled by over a hundred pounds of collected knowledge. Do people still own these? I wonder how many are burned every year. As an older child when I was a pre-teen, I read a lot of trash. Boring Archie comics and YM Magazine and those bizarre V.C. Andrews grocery store books full up of cruelty and horror. I still love gossip and how it constantly shapes and molds the truth in violent and cyclic ways. Encyclopedias I suppose, too, are full of it.

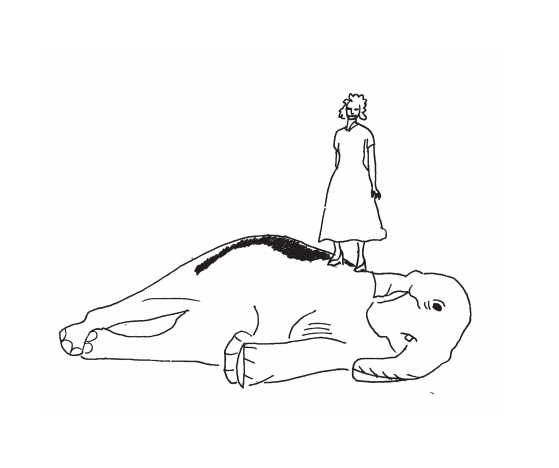

TS: I love your description of encyclopedias as “humans’ most tidy version of collected knowledge.” There is a cookie-cutter precision to them. Your book, on the other hand, doesn’t try to separate writing forms or genres. It engages history and culture through research and personal history as well as text and visual modes. The comic drawings play such a unique role, adding visual playfulness to the circus show that structures the collection. It reminds me of 19th century drawing as a way of summing up portions of text or complimenting them. The playfulness in the comics in your book offset the more serious concerns of the price we pay to see or run a spectacle, so the humor is double-edged and in line with the critique of a spectacle such as Jungleland’s animal show. One particular moment that stands out is the drawing of Jayne Mansfield on page 46. The caption reads, “You know which title I like best? I like to be called mother.” Of course, it is placed next to the story of her unsupervised son who was bitten by a lion at Jungleland, almost like a poster advertising the show. I was arrested on page 74 by “Black Panther Plays Game of Cat and Mouse,” which is a cartoon that works like an erasure poem of a news article. Besides Archie, what cartoons/comics did you love as a child, and how did this interest in them re-surface or evolve as an adult?

JQS: I loved watching cartoons when I was a child. Mostly that absurdist early Nickelodeon fanfare from the ’90s: Ren and Stimpy, Rocko’s Modern Life, that weird still-life-as-mediocrity show Doug. I’d wake up before anyone in my household to watch hours of them very early in the morning. I always read the newspaper funnies: Garfield, Blondie, Cathy. One of the most distinct thought-memories I have from when I was a child was, “I’ll never grow out of watching cartoons or reading comics and if I do, there’s something wrong. I’ve been replaced.” I guess I never really did grow out of them. I got into reading more high-brow comics in undergrad. I loved the Hernandez Bros. and read everything they’ve written. And I still subscribe to some serial comics. I am reading the over-hyped Archie reboot (it mostly sucks) and I’ve read all of Southern Bastards (better). I love trashy one-offs. Archie vs. Predator is so bad it’s good.

In undergrad I also started reading poetry and I was naturally drawn to hybridities: products of low-fi mimeograph tech, minimalist illustrations, mixed media. The New York School folks, of course. Joe Brainard. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and the collaborative Bean Spasms blew up my definitions of a text, of poetry’s relationship with the visual. My dissertation for my English PhD was about why poets use comics in their work and how to consider long-running comics as poetic texts (e.g. Dick Tracy, Nancy, Krazy Kat, Looney Tunes). I’ve figured out that I’m attracted to a lot of comics and cartoons that spill over the page, bound forms, authors, generations. That are so sprawling they can’t really retain fidelity to a single trajectory or author or the fantasy of original intention. What a manifestation for our messy lineage right now, our convoluted and often chaotic inheritances (national, personal). I also really like comics and cartoons that are boring. I think the disjunction between visual stimuli and boring content is a fascinating form of failure. Maybe I’m overthinking it. Or maybe I really did get replaced.

TS: I’m intrigued by your thoughts on stimuli, boredom, and failure. It seems like someone else’s artistic failure offers room for your own imagination to take root. For instance, in “Jungleland: A Genealogy, 1930-1951” (pg 62), the paragraph covering years 1941-45 unfolds the narrator’s own realization of the problem of building the spectacle:

[Goebel] acquires and sells an apex of 26 elephants in the span

of a few months. When we accept slight amazement and, in the

world of the imagination, it becomes normal for an elephant, which

is an enormous animal, to come out of a snail shell. It would be

exceptional, however, if we were to ask him to go back in.

What begins as a record of inventory of what is bought and sold becomes a critique, yes, but also a meditation on the imagination and expectation. In another “Genealogy” from 1919-1929, you trace the plane crash that involves one of Goebel’s lions. After the search and rescue is described, the 1928 record ends with, “She is unharmed and earns the nickname, ‘Leo the Lucky.’ I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming; the house protects the dreamer; the house allows one to dream in peace” (pg 29). We connect the lion’s cage to a form of house, but it is from the safety of our own houses that we daydream into existence the myths of other animals and people. Moments like this remind me of my own inclination to re-write movies that I thought did not touch on subjects the way I wanted them to when I was a child. In a sense, we’re always re-writing the dissatisfying. Were there particular moments in your research for this book that felt like facts or information failed in ways that allowed you to play with them in unexpected forms, to create a new ecosystem for them?

JQS: Yes, certainly. When I was diving into the research of Jungleland, it was like rowing around in a boat with a hole. Nothing stuck, few facts could be confirmed about specific dates, people, celebrities that were involved. “Facts” I collected contradicted each other. I grew up nearby to the site of where the zoo once stood in Southern California and spent hundreds of afternoons in the mall that stands there now. No trace of it. I was frustrated to feel so drawn to this strange place and to know that I had spent so much time at these very geo-coordinates and for my own memory to come up empty-handed again and again, a hole.

California is an elision. So much of the cubicle suburbs of California aren’t designed for longevity or cross-generational memory. And if you do take on sustained digging beyond surfaces (Hollywood’s specialty), there’s so much information to weed through that hasn’t been polished and reframed and memorialized and tidied up. It can all be quite honest about the violence that defines most of the history in this place and this nation.

I should mention that while I was writing the meat of this collection, I was also walking a lot in a park next to my house every day. I have severe, chronic back pain and during my first pregnancy, during which I wrote this collection, walking was the only thing that allowed me to stay physically functional. I walked an out-and-back through this park six, seven times a day. I probably have thousands of photographs on my phone from that period of time of the park. The same trees, the small bridge. Because what else. For me, there was a parallel between thumbing over the same missing information and walking the same path every day several times a day, thousands of miles away from Jungleland, thinking into omission and erasure, into my own boredom. Thinking around a path that feels trivial or immutable. Returning to the mall. To the little lion from Jungleland left to die in the Arizona sun after its plane crash. What did it think about while pacing its cage for five days before it was recovered and returned to its zoo, to its brand?

I don’t care for imagination in a vacuum; the supposed randomness of daydreaming. I am interested in dismantling the kind of violent fantasies that have fueled American land acquisition, unchecked entrepreneurism, and an image of American nationalism that relies on the maintenance of historical erasure, revision, and distraction. I am interested in walking in circles.

TS: I appreciate the pull to sift through unpolished information and unearth a more honest perspective of the violence embedded in every stage of our nation-building. Erasure is a hostile process – even to a reader. Sometimes, the way of filling in the gaps is to acknowledge that violence happened. Other times, it seems American history is obsessed with cruelty to the point of public de-sensitization to it. There is a spectacle in that. There is also money in creating a spectacle. One quote from Guy Debord included in the book that really stands out to me is this: “The admirable people in whom the system personifies itself are well known for not being what they are; they became great men by stooping below the reality of the smallest individual life” (page 27). Savage Pageant is steeped in this practice of personalities guarding spectacle, violence, and unchecked entrepreneurism as you say — from caged and abused animals to toxic seepage in the landscape. The genealogies capture the persistence in how land switches hands and yet the exploitative desires remain very similar.

I’m interested in the figure of Mabel Stark, the Jungleland performer, who enters the story being told in 1911 as a lion trainer for AI G. Barnes Circus. She’s one of the few recurring characters who isn’t a land/business owner. On the one hand, she upholds the violence of the Jungleland entrepreneurial spectacle by her willingness to participate. On the other, she’s deeply caring toward her audience and what they get out of the show. You quote her, “Most of all I was concerned for the audience, I knew it would be a horrible sight if my body was torn apart before their eyes” (page 38). Mabel participates but her performance also resists the violence others may thirst for. We see her creating and upholding the spectacle but then also being consumed and erased by it as history moves on. Could you tell us a little about why you chose to pull her history out of the unpolished information?

JQS: I found Mabel so interesting. On the one hand, she was the first of women tiger trainers in the United States, a “feminist,” and on the other hand—very obviously a caged lion, a fool, a show. I found myself thinking so much about her body. How she was quite literally ripped apart by these lions that she loved and returned to them again and again. How she circled around this idea of “taming” them and how much physical pain she must have endured in this lifelong compulsion. I felt that in researching this receptacle of gossip and violence, that I was also circling. I could not find who was responsible for a deed. And that that (mis)information and circling could also destroy me.

I wanted to explore Mabel for her complicated position of being well-intentioned, but that she, too, was reproducing the spectacle that would inevitably lead to her own self-destruction. She designed a signature white coat to hide the stains of her lions’ ejaculate during shows. There is an unnerving eroticism to power that is deeply entrenched in our national culture and what we find entertaining. I wanted to examine how US American violence lived impossibly inside a single body in time.

TS: I’m really taken by the different ways the violence of a nation/ culture lives in our bodies throughout a lifespan. It seems that what this collection captures is ultimate deterioration. The series of poems about pregnancy create a dark parallel as the titular savage pageant. As early as the prologue, resistance to this bodily spectacle emerge: “When we were little, / my sisters (being the youngest, I too) thought / the pregnant form was disgusting. / Nothing is as plain or crass as expecting” (4). This poem begins with positioning yourself as someone who doesn’t want to participate while it ends with the birth of your son, “Sometimes you can’t put all the bones / back where they’re supposed to go. // I had a boy and they took you out with a knife.” What is a greatly interior and body-changing individual experience is also commandeered by outrageous hospital bills, public policies, grocery store tabloids monitoring celebrity “bumps,” etc. Yet, this poem ends with a direct address to your son; a “you” that seems to shut out the rest of the world while ushering him into it.

I see, at least in America, an increasing willingness or necessity to participate in spectacles. From the multiple approaches to storytelling you provide with research, I’m also aware that it is possible we have overlapping or concentric public displays all at once. Do you feel like there were ways in which experiencing and/or writing about pregnancy gave you more insight into what it means to participate (willingly or unwillingly) in a spectacle? Or insights into the possibility of taking or making refuge from the spectacle?

JQS: I think that being pregnant unwillingly “permits” public inspection and there is no way to not participate in the related spectacle of the growing body during that time. It perhaps seems innocuous — like, who cares about the Hallmark image of pregnancies, or what’s the big deal, it’s just celebrating a new life. But it’s beyond. There is no innocent form of spectacle. And I think the spectacle of pregnancy and its affiliated joy that I think many truly enjoy (including myself) mollifies terror, irrationality, the body bleeding and stinking and breaking and potentially dying for the new. I was teaching sections of creative writing up until I was eight months pregnant and received many comments, all well-intentioned, from my students on my growing body, personal decision, even my changing face. It felt shocking and I hadn’t realized the switch that happens for those whose bodies are quite literally at the hands of the state because they are carrying.

There was also so much general, “well-intentioned” advice about what to eat, when to eat, whether to exercise, how to exercise, how to birth, where to birth. Of course, these matters are all raced and classed. I felt very privileged in my small luxuries — money for prenatal care and for a standard hospital delivery. But I still remember feeling uncomfortable that I certainly couldn’t afford a doula or a midwife or a crunchy birthing center experience, and how others are just totally fine that the standards of care are appropriately contingent on how much you can pay. I knew someone who was pregnant that expressed unabashed alarm at how many Black people were at her intended birthing hospital when she took a tour and she worried about the quality of care. It’s disturbing mostly because of how obviously these hierarchies continue beyond birthing (the choice of daycares, schools, hundreds of forms of access). Which in retrospect is all hilarious because no one really warns you about how much society fails you after pregnancy and birthing or how buildings, whole systemic structures, the standard “workday,” are all designed with a spectral / invisible idea of who cares for the children and where and how. For the children themselves.

I think that we have lived in a culture of distraction and spectacle for a long time that bleeds into everything, every aspect of daily life. I wish to say I do not want to be a part of that, but of course, I have been, I am. You can’t put all the bones back. And I cannot also expect to control how much my son is affected by this distracted, violent world and its hierarchies and its repercussive histories. The poem you reference was the last poem written for the book and it is a bridge to my next book, which is mostly about my mother (and her mother). Which is to say, my son is part of that fierce, survivalist lineage. Which is to say, sometimes I wish he were not.

TS: In writing from your lived survivalist lineage, honesty about the absence of virtue inherent in our cultural or individual participation in spectacle is a practice and even a method of combat. Your book points to this in so many ways, particularly with the way you engage social theory. In “Act IV: The Illness,” you begin this section with a Debord quote that includes, “But a lie that can no longer be challenged becomes insane.” In your work, I also see that the people subjected to the lie become destabilized when they cannot create change. “Act VI” references many mental conditions and disorders proliferating from suppressed or poisoned psyches as a result. How can writing unearth “archives of harm” (pg 108) without causing more harm? How do you think about the interplay of survival and vigilance as something passed down in terms of this project or your next?

JQS: Thank you for this energizing question. The last chapter of the book grapples with how a history of violence manifests in seen and unseen repercussions across time. Spontaneous combustion, psychogenic illness, bones unearthing themselves, trace toxicities in the soil. As you suggest, I don’t think there is a clean “way out” of the spectacle in US American culture and its ongoing violence as a poet or otherwise. We perform and indulge in spectacles every day, scrolling. I think, however, there is a tipping point to the facade, which manifests in mystery, ghosts, weird feelings in buildings, deja vu, blips in the script.

Psychogenic illness, or “mass hysteria,” occurs worldwide and its direct causes remain unknown, but researchers hypothesize that these episodes are caused by a mixture of intense social constraints and hazardous environmental factors. Look at where we stand. What an intense amalgamation-stage for that type of break. And how would we know if we all went “mad” if we’re in the same schoolroom? I don’t want to mince words. I want to suggest doom because our history is dooming, but I also want to suggest that these symptoms break the mirage and perhaps the relentlessness of these cycles in history.

In several readings that I did before COVID precautions from this book, I asked if people wanted me to end on the stage (the poem “Build a Stage”) or in the street (the poem “Jungleland Had Many Names”). One hundred percent of the time audiences request the street. Manic laughter is the street. Revolt is the street. Guy Debord and theory and academia are the stage. Neither are correct. Both are necessary. The street signals direct action. I am hopeful.

At the end of this closing poem of this book, I consider the schoolgirls that can’t stop laughing, those girls that could only describe what kept them laughing for months (to the point of vomiting, fainting) as “ungovernable things” moving around in their minds. These are restless times that require restless minds. In my mind, unearthing an archive of harm irrevocably reproduces the spectacle it wishes to dismantle. That is the tax. But poetry, unlike more linear forms of storytelling, calls for neglected peripheries in provoking these images. Yes, this is a survivalist book in the way that we are symptomatic even if we wish to will ourselves not to be. Yet we are alive amidst all this rubble. I provide no answers in this book, which is the only way to appropriately conclude a spectacle that desires to combust itself.

A spectacle relies so heavily on a neat ending that gives you good feelings or makes you feel like you’ve learned something that you already know. A spectacle must also end, which this book does not. Like I mentioned the first poem in this book is a bridge, which considers a more personal plight of my own survival as being the offspring of the American War in Vietnam and the monsters that diasporic experiences create for show and for survival. I guess it’s always been about survival.

(comic excerpted from pg 83)

(comic excerpted from pg 83)