We started this essay wanting to write about our own relationships with ritual, trauma, addiction, recovery, and art. We planned to pull ten tarot cards total, finding the current between us. We wrote about what was happening in the moment we pulled the cards, as well as the traumatic surfacing that occurred. During the process, Kirin’s younger brother, Abdul-Qayyum, died by suicide. The terrible synchronicity of this death as Kirin herself reflects back on her own attempts communicates the uncomfortable truth: mental illness is real, lethal if untreated, and often runs in the family. It raises questions – the whys and what-ifs, of course, but also, what is the line that separates him from her, and how did that line determine different outcomes? We record this by leaving the work unfinished and unresolved. The absence is a space for grief.

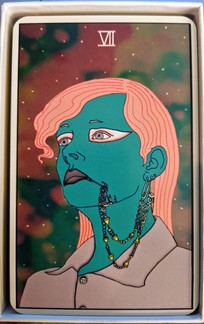

SEVEN OF CUPS

Daydreaming, choices, fantasy, illusion, imagination.

Having many choices, overwhelm, indulging in wishful thinking, falling into dissipation (wantonness, disorganization, addictive patterns)

Insects are always en masse it seems; where there is one there are others, and there is always, always one, you just can’t see it yet. I peek from the bedsheets and watch as piles of drying flowers, their wet rot sour scent now shifted to a dusty one, attract flies. Excess leads to decay; what is consumable surpassed, the remains pile up and insects swarm. I bought the flowers myself. I got the bugs for free.

Excess leading to destruction sounds about right for me. I always bought my drugs in bulk – not from greed but from anxiety. How I hated having to ask for what I wanted, the reaching out, the talking to a stranger, the waiting, the hoping and the hunger. I once dropped $400 on cocaine, which meant I couldn’t pay rent. I paid to buy myself more time away from the next instance of having to talk to someone. I don’t even like cocaine that much.

I don’t use anymore, but I still anxiety-spend. The groceries I bought rot in the fridge. I buy more, load the fridge with food I imagine eating. I imagine being someone who cooks, someone who eats vegetables.

The clothes in my closet are vegetables too – some now buckshot with moth holes, some never fit. I decide I will be a pattern mixer, no, bright monochrome, no, all black. I will be someone who wears outfits, someone who goes to parties and clubs. I will be a maximalist, excessive, extra, multitudinous as glitter and just as sparkling.

My fridge, my closet, filled with anxiety. Anxiety is hope-adjacent, its glaring reflection – both look to the future with expectation, what if, what if.

I put on the same old tennis shoes and the same old jeans and I leave, the door shut but unlocked behind me. Never locked.

EIGHT OF PENTACLES

This card is about the rewards of labour, the benefits of practice, craft, routine. The web is regular, but not uniform, the possibility of creativity and fluidity within the boundaries of discipline are emphasised in this image. I can’t help but think of the carnivorous intent of the spider whose art is murder.

The Marsh pitcher plant is carnivorous, it is structurally simple, comprised of meaty tubes, covered in slippery hairs: insects drown in fluids at the base, bacteria breaks them down.

I have just watched a film full of insect, teeming life and queer sexuality. A conventional story arc of infidelity, desire, jealousy, and revenge is made strange by pastoral scenes of wet grass, spider-webs, horsehair, a woman writhing in the dirt in a filthy floral dress, blood-covered walls, and split cabbages.

The insects have been bothering me. White curtains that were once a protective enclosure, now riotous with bugs. Small black dots. I notice punctures on my arms, I read about recluse spiders and necrosis. Twenty or thirty dead insects float in my bathwater. Sweat draws them, as does humidity. A moth alarms me, flying into my face, huge and frightened. I turn off the light to calm it. Pitch black dark and I can hear it cowering near the bed. Spiders everywhere, huge Catherine wheels shedding spindles, silent, creeping aliens. Half-decayed. Piles of legs all over. I sleep in a pillow fort, the blanket over my head, a haven of warmth and sweat.

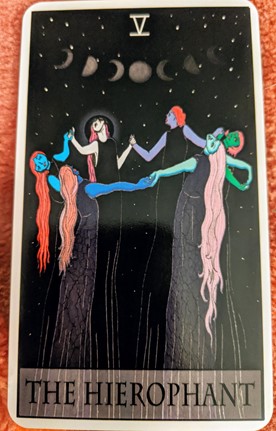

THE HIEROPHANT

Inspiration. Spirituality. Pursuing Knowledge.

The bridge between deity and humanity.

Twenty years ago, just before my 16th birthday, I tried to kill myself by injecting air into my veins. We had syringes all over the house. My little brother had cancer and they were leftover from treatments. I would go to the bathroom late at night, take a syringe, and slowly push it through the skin on the inside of my elbow. I nicked a vein. Deep purple blood pushed the skin into a round bubble where the needle entered, and then streamed out. I did this every night, at some point I shifted from trying to inject air into my veins, which was apparently very hard to do, to trying to withdraw blood and store it in the needle. The tender skin bruised deep, and eventually the needle grew dull. It wasn’t the first or last time I tried to kill myself, but it was the only time I tried that way. The bridge between deity and humanity isn’t so special, we call it dying.

I’m 36 now. My dad died a few weeks before my 28th birthday. I’d stopped being suicidal for a while, but his death made it final. I do not believe in an afterlife, and the permanence of his absence reduces me to a child. I don’t understand it. The permanence. How could anything be so real, so final? Since he died, I am no longer suicidal, I am terrified of dying.

I want to end this on a happier note – inspiration! knowledge! spirituality! but my head’s just not there. I am searching for these things, always. Maybe I’ll feel better in the morning, more inspired when I’m not so ground down by the work required to survive, the accumulation of a long day of giving until I’m not sure I exist anymore as myself, an entity unto herself. A spirit.

FOUR OF SWORDS

The Four of Swords is a loss-of-innocence romance. The lamb sits quietly waiting for the sky to fall, waiting to feel the salty taste of blood on her tongue, the raw lanolin stink of shearing. She can prevent this only with her mind, so she needs to fill it with glitter and rain, with arctic shimmer. If she is still, and silent, if she doses right, she can stay safe.

Anxiety symptoms are the exact same as overdose symptoms are the exact same as heart attack symptoms: palpitations, visions, nightmares, hyperventilation, disassociation, dread, the feeling of imminent death.

A therapeutic dose of poison is not best administered by someone already halfway to oblivion.

You will do anything to buy five minutes of time. Distraction is key. You can try on ten outfits: tutus, a child’s fairy costume ten sizes too small, lipstick smeared all over, a look you call “the beauty queen” where you see how many layers of slicked on kohl and black shadow and glitter glue you can cry off. Like a conservationist working with oils, you take off a layer at a time, to reveal the sublime light beneath.

The film I saw last night was about a trip to the New Mexico desert. A woman gasps at her oxygen mask, she wears white clothes, she listens to false prophets. Eventually she entombs herself in a porcelain chamber and waits for death.

When I visited New Mexico, I collapsed in the desert with altitude sickness and bird flu and chronic stress. I stayed in a hospital thousands of miles from home, alone. I took anti-anxiety medication that made me feel better than I had felt in months or years. For two days, I was able to control the swords with the wild crystals in my mind.

KING OF SWORDS

Intellectual power, authority, decisive action, truth

A blade cuts to the truth, unsparing. The Attan is a Pashtun folk dance with pagan roots performed by men. In some versions, the men dance with a colored scarf in one hand, in the other, a sword. In other versions, a man dances with two swords, a third in his mouth. Articles online describe it as a dance preparing for battle, but also for weddings and celebrations. Versions of it induce men into trances, almost religious ecstasy. I’m unsure how much of the war-monger battle-hungry fierce warrior associations were ours, versus painted on us again and again by those who could not conquer us, to justify their losses. And in painting us with this brush, we are rabid animals to be put down.

I found a photo of Pashtun men doing the Attan to prepare to fight in World War I and the image makes my chest ache. There is a kind of innocence that was lost during that war and remains lost. I wonder if they survived. I wonder if they were properly armed, if their lives were valued. I fear they were nothing but chum to the British. I wonder if they were scared, or if all the rhetoric about our people as fighters permeated their bones, so that they had no doubt they would survive.

The King of Swords is intelligent, he has clarity. One of the great Pashtun poets, Ghani Khan, the Mad Philosopher, said of us,

“The Pashtuns are a rain-sown wheat: they all came up on the same day; they are all the same. But the chief reason why I love a Pashtun is that he will wash his face and oil his beard and perfume his locks and put on his best pair of clothes when he goes out to fight and die.”

Maybe I have it wrong, then. Maybe they knew they would not survive. Maybe this is why they danced.

THREE OF WANDS

The three of wands are bound together tightly. If you tried to prise the wands apart, you’d scar the young wood. The colours in the centre are pure violence.

Three is a dangerous number. Three people go into the woods, one of them kills the other two, or two of them kill the other one. That’s why so many murder ballads are set in the forest, the woods, the corrupted idyll.

There was an old woman and she lived in the woods. Weile Weile Weila. There was an old woman and she lived in the woods. Down by the River Seile.

In these ballads, pregnancy is the precursor to death. It undermines a man’s status, questions his rights and his ownership, puts him in a predicament. A meeting after dark in a moonlit forest, a clearing at midnight, the witching hour.

There was an old woman. How old is she? Forty? Thirty-Nine? Thirty-Two?

Weile Weile Weila is from the Middle English term “wailowai”, a cry of grief and lamentation. Who is the lamentation is for? Not for the woman who commits infanticide: She stuck the fig knife in the baby’s heart, weile weile waile, and who is in turn killed by men in uniform who come to her house at night: They pulled the rope and she got hung, weile weile waile.

Weile weile weila for all those trapped in inhospitable land, failed crops, food deserts, the engineered destruction of ancestors.

But a baby inspires pity, the innocence, the immaculate purity of a newborn, that life is weighed in the balance and seen as more deserving than that of a woman, a Hag, Haxan, Hedge-Witch.

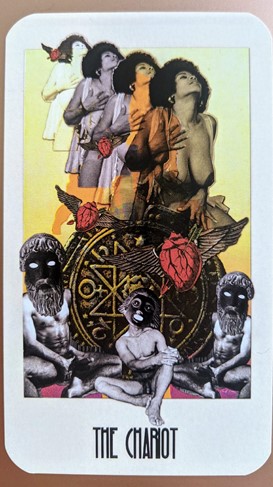

THE CHARIOT

The Chariot is about the conflict which opposites create. These opposite forces are often thought to be the carnal and spiritual forces within man which need to be balanced. They can also represent the wish to go forward and the simultaneous wish to stay secure in the tried and tested. The chariot represents the quality of energy needed to fight for a desired goal. It shows a struggle or conflict of interests and can mean a fight for self-assertion is necessary.

There is a fight coming and I am always ready. I laugh and roll my neck. Today the wind was forceful; it downed power lines, sent tree trunks to shut down streets, blew a wildness into my hair and eyes. All things beautiful have in them the power to be lethal when amplified, maybe this is why so many try to diminish a woman, to keep her small. In tune with nature, we crones and maidens step into power in the woods, where fecund soil feeds on the blood and bones buried deep below. Blood and bones and all forms of death are so close to the animal/woman. l love the company of women, how we amplify one another’s power until we are all electric, how we might fail to defend ourselves, but never fail to defend a sister. The coven manifests in the nightclub bathroom, in the slumber party, in the eye contact on the bus when a man leers at one of us.

Even as I write this I think of those women who failed me, and I remind myself they are not women, those worms. I grind my boot.

I’ve been reconnecting with the danger inside me, without realizing I was doing it. My black blade, my sneering red mouth. I recognize myself best when I’m angry, or bleeding. Trauma, baby, sure, but it is what I’ve known best, even if I don’t want that to be true. I sometimes think I was born at the wrong time. There is a warrior woman with long gnarled hair, on horseback, her sword bloody. The heads of men knotted together by their locks, tied to gear like just another bag. When she laughs, the wind sends trees crashing to the ground.

Even in this time, I was once a girl who kept a razor blade in her mouth, ready, ready.

THE HIGH PRIESTESS

I am not the high priestess.

She is on the other side.

She is the dead girl in the picture on my grandmother’s dresser wearing a high-necked secretary blouse, dark hair coiled in a bun, tan trousers, a bewitching smile.

She is holding a handful of green glass flowers

She is crying out.

She gives me a crystal rosary.

She is the candle “for the unborn dead, murdered by their mothers” standing on the altar in my childhood church beside a statue of Mary: virgin, pregnant, fourteen.

She holds out her queer light to me.

She has no need for the moon.

TWO OF CUPS

On the day my brother died, I drew the Two of Cups.

Unity. Relationships. Balance. The flow of love between two people.

About the Authors

Kirin Khan is a Pukhtuna from Albuquerque, New Mexico, who writes about trauma, the body, sports, violence, immigrants, and queerness among other stuff. She has received fellowships from PEN America’s Emerging Voices, San Francisco Writers Grotto, and San Jose State University’s Steinbeck Fellowship, and residencies from the Vermont Studio Center and Tin House. Her writing has appeared in Corporeal Khora, Nat. Brut, Your Impossible Voice, 7×7.LA and elsewhere. Check out her work at kirinkhan.com or find her on Twitter @kirinjaan.

Laura Joyce writes about ghostly traces, queer light, and occulted histories. Her work has been published in 3AM, Montevidayo, Entropy, PLINTH, and Burning House Press, and anthologised in Egress, The New Gothic, and Murmurations. She is the author of two horror-experiments The Museum of Atheism (Salt, 2012) and The Luminol Reels (Calamari Archive, 2014) and a book of criticism Luminol Theory (Punctum, 2017). She co-runs HEX with Jodie Kim.