Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Jay Besemer

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Jay Besemer, author of Theories of Performance.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Jay Besemer

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Jay Besemer, author of Theories of Performance.

How many languages does our body hold? How many ways can a body be read? What are our thresholds for experiencing how others project “readability” onto us? Theories of Performance disrobes expectations as the speaker states, “i’m not broken down into something with /or without parts. the /grammar here is a / unique body. it must / be said: it must / be done” (27). Yet, in these poems nothing ever feels “done” or final- they relish the prismatic plurality of perpetually becoming. In this space, Besemer gives us the possibility of finding the animals that we are, that we’ve forgotten we are. Attentive to its audience’s own holistic experience of engaged reading, this collection offers both refuge in embedded moments for pausing and resources for deeper understanding of the creative process, expanding the limits of how a book can be “the all-access wristband” (14).

From Theories of Performance:

someone somewhere digs a

visionary canal. my spoon,

my buggy fall in.crepey matter. light skirts

the brightwork on the

death-long barges. it isn’tto eat anymore. it’s all

developers & single-malt

jargon. i don’t do walrusesor pancake. i faint at

the sight of aioli. may

i just say the magicwords to buy my exit

strategy. may i just say.

my, how predatoryyou look today, my sweet

fuck-all, my usual

suspect, my reflection.

***

Tarpaulin Sky: The speaker in Theories of Performance has a complicated relationship to the wild animals that paw, swim, and scavenge through the book. We’re briefly introduced to badgers, eels, fish, mice, hummingbirds, moths, and deer. These instances often feel like visits from or reminders of more feral, intuitive, and communal ways of being. The wildlife has the potential to harm us but also to comfort, protect, or teach us. Beyond specific creatures, the word “animal” itself appears at least 25 times in this collection. There seems to be a lot of pain embedded in the ways humans distinguish themselves from other animals and we see this contrast when you write, “animals make animals, homes” and “humans make themselves unwelcome” in the same poem. Bonding to or channeling wild animals may offer a respite from feeling like existing is a performance that questions “whether the public face can ever really be honest or accurate” (79). Yet, we’re not left with a hopeless divide as these poems forge connections: “is it conceivable—for / a regular human animal— / to fold up the dread into / a bundle of shrunken / meat, set it down…” (68). I’m wondering what your relationship to animals was like as a child—did you have deep bonds with any animals or fantasies about transforming into any wild animals? And if so, what sort of resource did this offer you? Did the animals so prevalent in children’s books impact your imagination?

Jay Besemer: i’m going to rely heavily on images for my reply here because i tend to be verbose & over-explain. so:

here i am, as an infant, with my parents’ cat lucky. i think lucky taught me more about movement & perception than i realized or can access in cognitive memory. my parents had to give him away soon after this because he became aggressive toward me—or because my mother developed an allergy to cats after my birth, depending on which parent you ask.

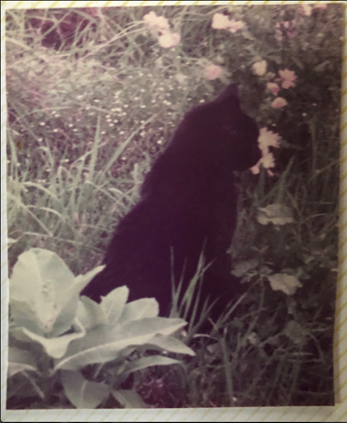

this is my father’s cat jason (known more commonly as “boober”) who was part of my life from age 6 or so through my teens. i took this photo when i was a teen helping my father build a log home. boober was a shy, roving shadow who loved to go out in the rain & then come in soaking wet to snuggle on my lap. he also had other animal friends at this time, most notably a skunk with whom he would play at night.

my childhood bonds with actual animals tended to favor relationships that took place in my father’s world, though i also had various small pets like fancy mice & hamsters who were important to me in my custodial home, with my mother. the kinds of deep animal communication/communion i became accustomed to seemed focused on larger animals, though even with the small rodents there was an affinity that became important in adulthood when i worked with rats & mice for a time. i also had many affinities/encounters with other animals, particularly snakes & deer. when i was an infant/toddler in frankfort, kentucky, there was a nearby game farm that had a petting pen that featured tame deer, & deer have always fascinated me. i remember one very noteworthy time when i was playing at being “a little deer” & i bedded down—& fell asleep in—a patch of poison ivy! i think that turned out better than it might have…

animals in kids’ books & media definitely impacted my imagination. i think i’ve always held a sense of the personhood of animals, & sensed a tension between the “talking (human-like) animal” trope of animal story characters/myths, & the communication that animals do without speech. my own relationship to speech & language has been complex in ways that i’m only now coming to understand, but for now, i can definitely say that i trusted animal communication more than speech because there were no words to hide behind. when boober came to lie on my lap & lick himself dry after a rainstorm, i didn’t need words to know he trusted me. his whole body told me.

TS: I love these photos, thank you for including them. I’m drawn to your point about how physical expression is more genuine or trustworthy than speech because there are “no words to hide behind.” There is an evolving tension in this collection between an oppressive “holding pattern” (22) that comes from culturally constructed norms in appearance and performance, and the desire to have bodily change that allows full connection with the self. We see this manifestation of desire in the poem, “Ethereally,” when the holding pattern is lifted/broken and the narrator captures the ways in which hormone replacement therapy affects his body. The narrator poses how “my nativity is long / gone” (complex enjambment!) and how:

motivational slogans

crop up on my body

in sprays of acne.i like this. the acne

is proud. i’m

getting a handle

on my abjection.i navigate a dogma

of neckbeard. i

have no fallback

rebranding plan. (17)

This moment brings up how a transitioning body may impact the need for language to clarify or “to hide behind” it, as you say. Here, the body creates a new language (via acne) as motivation. As the neckbeard becomes an incontrovertible truth—a dogma— I wonder what you think about desired visibility and how that changes one’s relationship to language?

JB: one of the great tensions in my life, including during transition processes, is that between scrutiny & presence. or scrutiny & recognition, in the sense of acknowledgement-as-the-being-i-am. that recognition means a spaciousness that could hold & engage with what i am even without the need to “understand” or “relate to” or even perceive the whole of me at any time. (how could that whole-perception be possible anyway?) is it possible for others to encounter & accept the reality of me (or themselves, even) without necessarily trying to plop me into some prefab, legible category—including “transness”? this is a being-&-becoming issue, so i could go on like this forever; the point is, i find myself resisting the language that others impose on me without necessarily being able to deploy my own language against that. at least not in the traditional sense of language.

i have physical & cognitive difficulties producing speech. you may have seen me say this in other places. at times, even written language is difficult for me to produce, at least in ways that are held as traditionally “communicative” in western civs/cultures. so lately i’ve been very interested in other ways, perhaps non-linguistic ways, of making meaning, or even language. languages of play, for example, that my cat jet & i have devised together, are extremely effective in mutually meeting needs & desires, & they don’t even require a vocalization. of course, jet is very vocal, so there’s lots of noise anyway–but this is a matter of a language of mutual attention, & not “what does he mean when he says mmmmmpr—iip!!?”

i wouldn’t call this more “authentic” than wordy language, especially as that word is rapidly losing its meaning. but the animals in my life have not been interested in dissembling, manipulating or deceiving other animals, including me. they wanted their needs met, their desires recognized & fulfilled. i want this for myself. to approach a being with that mutual attention is part of what i need. i’ve always needed that.

another animal example to illustrate this need: when i was 18 i had a 6-month internship on a dairy goat farm. in the course of that, a small group of “first fresheners” dropped their first litters of kids. mostly goats were left alone in labor, with occasional checks for problems. one goat kept crying—it was clear to me she was terrified & in pain, but there was no medical difficulty. she was just…afraid! i couldn’t figure out why the others didn’t feel it too, but when i said i had to go into the barn & sit with her, they basically said “suit yourself, weirdo.”

i sat on the straw in her stall with her as she gave birth. i can’t remember whether the kid was fully out when i finally had to leave for my bed, but when i saw her the next day she came right over to me, bleating excitedly, & leaned/rubbed on me—that’s a goat hug. she did that every time she saw me since that night. if i had said to her, “now, anisette, you know the birth process is a natural thing & there’s nothing to be afraid of, you’ll be just fine!” it would have been ludicrous. but i didn’t say anything, not in words. i was just there. (here is anisette; i think she may be wearing one of my bandanas. the other pic shows 18-year-old me with anisette & fungi, her mother. notice how she leans on me!)

i think word language helps us perpetuate the convenient self-delusion that we are not animals too.

TS: Before we explore some of the great ideas you just shared, I hope it’s okay to keep parsing your own term “holding pattern” a bit more to unpack it. You write, “someone in a / holding pattern / looks like this. so / much in abeyance // so much meantime” (22). Holding implies more than a time period of little change. Holding also indicates the physical boundary of the body and the way we form identity based on the rigidity or porousness of that boundary. It is seen in the way words are spliced and divided, enjambment and line breaks becoming essential to the circulation of language from the body of the poem onto the reader’s tongue—the physical tongue, the tongue of the mind.

However, the body communicates differently than what we wish to communicate to create integrity to our identities. These points of tension are also entry points for others to relate or understand us. What language of the body do we need to recognize or validate? What ethic does a changing body have to teach us and others?

JB: i keep orbiting your opening-out of the word holding. it is a great word because it shades into both intimacy & confinement. when i hold jet, or my husband, that’s a language too, right? it’s the language of mutual attention i mention earlier, & it’s goat hugs, & wet-cat snuggles. it’s making & sharing a space together, a generous affirmation of the finite nature of any body. all our bodies change. i recognize jet’s aging in the body’s language of pain; because my own lifelong arthritis is spreading now, i know the weakness & stiffness he displays in his right hip because my left hip does the same thing. a language & ethic of mutual attention could emerge from compassionate awareness of one’s own changing body & emanate to include—to hold—others.

or like, in more grad-school terms, the language & ethic of mutual attention through changing bodies operates against the continual displacement of bodily difference & change onto abjected others in the interest of privileging the ideal (& therefore unchanging) young, white, healthy, able, athletically toned, masculine, wealthy cis male body. dig? ;)

TS: I really appreciate your concept of mutual attention. I’m also thinking about your comments on recognition as spaciousness to engage someone fully without the need to “understand” them entirely. A kind of acceptance that allows for attention without the need for authority on/over someone else.

I think this also gets at the relationship of a reader and writer. Your book is so acutely aware of the reader and gives attention to the reader’s potential needs, which we can experience through the deliberate pauses. I found myself appreciating these respites as space to wander—sometimes mentally due to the outside world, sometimes emotionally because everyone brings their momentary feeling into reading a book. I was excited to find at the end, you actually address the noticeable structure of pauses that frames this book. You write, “”The pauses acknowledge that reading is a physical experience, involving readers’ and authors’ changing bodies, over time and in various states of being. A space for rest, contained within the book itself….(133).” It can be really challenging to give ourselves permission to claim this kind of space. This explanation also points to how the contents of the book and the interaction/process of reading itself may necessitate a rest. As someone myself who grew up with a chronic illness that required a lot of rest/pausing that more healthy bodies didn’t need, I am wondering how your own experience with chronic illness impacts the ways you think about attention for the reader’s care? An alternative question is: beyond the reader’s experience of engagement, how did your awareness of pauses/pausing shape your own writing process of this book?

JB: thank you for the observation connecting the mutual-attention space with the awareness of readers built in to Theories! i hadn’t consciously put the two together but i really think you’re right. i think there’s a commitment to the beings we encounter & engage with inherent in this mutual-attention form of language, & i welcome the chance to go deeper into the way that commitment forms & informs my poetics with regard to this specific book.

what i learned from my illnesses has absolutely informed my awareness of the bodily realities of my readers. one basic & obvious thing is the recognition that many of my readers are also living with illness & disability. i know that i am able to breathe a little easier, relax a bit more, when i encounter a printed text or other artifact that overtly acknowledges or addresses my needs as a human animal carried by a sick, aging body. in my structuring the book, & in the author’s note you quote from, i wanted to provide the same clear affirmation of the realities of readers’ bodies–whether they experience impairments or not. we live in a culture that loathes physical limitations & discourages people from meeting bodily needs except where those can be instrumentalized by capitalism into the “wellness” product, or as some kind of managerial scheme to maintain a docile & productive workforce. the more openly the most vulnerable people can claim their needs & expect to have them recognized, the easier it will be for those needs to be met, not denied or refused & punished. so there’s a definite political element to my approach to the needs of my readers, & the mutual-attention languagespace.

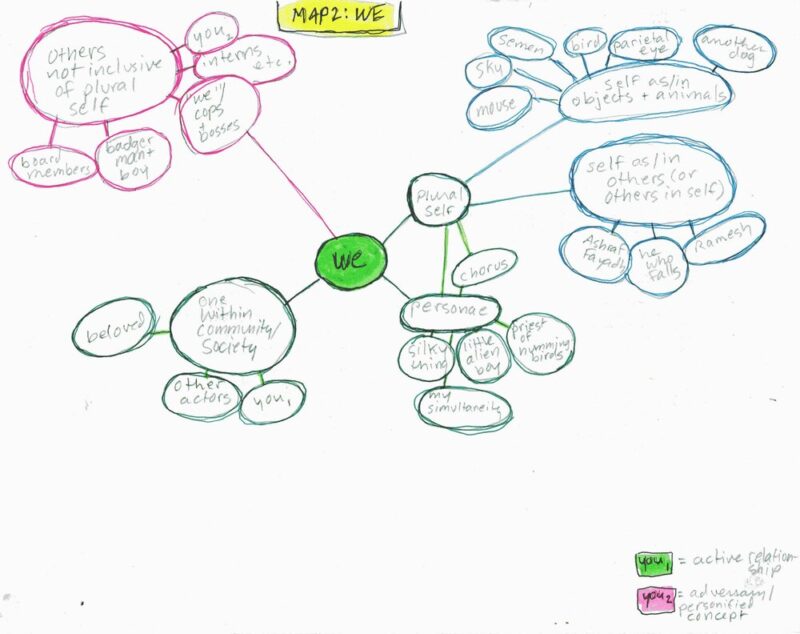

i’m not sure whether/how the attentiveness to readers’ bodies entered directly into the structure of the book while i was writing it. the structure actually emerged in revision. i just re-read the supplementary texts i provided for the “concept maps” i discuss in the author’s note, which are available here (scroll down fully): http://www.letteredstreetspress.com/theories-of-performance.

there may be some additional insights there. i also attend to particular bodily realities as they enter specific poems—that’s mentioned in the author’s note too. i can’t language the unlanguageable that often occurs in my body, but sometimes the poem itself functions as an attempt, & i feel the attempt itself is of service. it normalizes the bodily experience as well as its impossibility to squeeze into language–neither of which are shortcomings or failures of we who experience impairment, or attempt to place those experiences into language that is also largely meant to exclude them.

TS: These maps are an exciting extension of the body of this book: the book as a physical presence extending onto the internet; the book as a thing made of words that compose a picture. I think of sigils when I see your concept maps in terms of a visual representation of an outcome as well as a container of elements in flux. As I grow older, one thing I love is the constant rediscovery that multiple emotions can occur within me at once and they are all valid. It is like how many voices in an argument can be true and heard if we can give them connection. In the maps, I’m drawn to the multiple personae carried through: priest of hummingbirds, silky thing, little alien boy, my simultaneity. In the map of “We,” these connect with we—a sense of community— and a plural self, which touch communities that do not involve a plural self. This relates so much to mutual observation of others we have been discussing. How do you see the process of writing included in or exposed by the final product of a book? What made you know you needed to share these maps?

JB: i love the last question! my answer is unsurprisingly multi-layered, but the main reason i wanted to publish them as well is just that—love. i love the maps; i think they’re beautiful as art-entities in themselves, a bit of reverse-ekphrasis or intertextuality emerging from a writing process. but they’re also a writing process! a process within a process, where each map might be imagined as being contained within the others.

i also felt a need to make a more spatial representation of my cognition for & from this book. concept maps work so well for me because i am not a linear thinker. i think in pattern, relationship, & resonance. i am realizing that i take in everything at once & process it by applying various filters; the maps exemplify that very well. i can code-switch into classical logic & other linear models when i need to, but it takes a lot of energy. so including the concept maps is a space-making move, presenting my cognitive reality as part of the package of my plural self! my former therapist once observed that i “think in 16 dimensions,” & the concept maps are the only things besides poetry itself that can contain that. thanks for your observation about the maps’ resemblance to sigils! it’s probably not coincidental. at one time, i did a lot of sigilizing.

i’m also very committed to destroying received notions about how poetry, in particular, comes into being, coalesces or collides into a book-shape, & goes forth into the world. presenting the maps as part of the whole project makes it possible to imagine or recognize processes that resist more standardized production models.

i’m really intrigued by your phrase, “exposed by the final product of a book.” it seems to reflect some of what i’m getting at here—a dispelling of illusion, like toto pulling aside the curtain to expose the wizard of oz as the de-romanticized nobody he was. am i reading you right? is there more?

TS: Yes, that’s totally what I mean. Dispelling of illusion about how poems are written. And, also, how books exclude certain parts of their creation in the editing process. To me, books that expose the writing process lean into valuing writing as labor, and I really love that there is a stand-alone companion to the book showing thought process, allowing for multiple readings to exist. Their inclusion feels very generous to readers who are finding pieces of their own self/ selves inside the pages of Theories of Performance. The concept maps feel, to me, very inviting because I can see how they function to include more readings and readers.

As a final question, are there certain books/music pieces/visual art that you’ve been influenced by or that resonate with your sense of how the process of making or revising or experiencing is accessibly integral to the final project? I’m also intrigued by your process of taking everything in at once and distilling it through “various filters.” Are there certain filters (dimensions) you can identify yourself leaning into and cultivating more than others for a current writing project you’re working on?

JB: okay good; i’m glad i picked up on what you meant. i’m glad you think the maps contribute to the valuing of writing as labor, because that’s an orientation i work from & try to be overt in putting forward. same with the observation that the maps empower multiple readings. i’m glad for that reflection because my poetics actively requires multiple readings—that’s mentioned in the “About this Book” we’re all delving into. reading is also labor, & the book recognizes that. i find that readers of my books are very much, & vitally, sharing in the labor of finding & creating meaning.

i need to clarify my comment about filtering. i experience the world as i described, so that situation is more a part of my living process than simply my writing process; it includes the writing. i find it difficult to process incoming sensory information, which means i don’t have an easy way to filter out what’s coming at me. i get easily overloaded, so in a way writing itself is a filtering process—a way to offload my sensory processing to a less immediate location than inside my own body. it helps me navigate everyday life. so this intensity of sensation, thought & feeling enter my work directly & largely shape it in form & content—readers get a pretty direct approximation of how i experience the world.

the question about “filters” in my current projects can be addressed in this context, because right now i’m working on prepping my 2020 journals for possible publication. the book that’s emerging there is a chronicle of precisely that labor of living, including articulations & engagements with these very experiences (& plenty of writing-process stuff).

i also like the question about other forms of work that may include such exposure of their own making. i feel like I know & love a lot of those, but the one that pops up first in my memory is by one of my favorite filmmakers, Apichatpong Weerasethakul: it’s called MYSTERIOUS OBJECT AT NOON: http://www.kickthemachine.com/page80/page24/page16/index.html.

it’s described as a documentary, but it’s a documentary about collaboratively finding a story made up in an aleatory, improvisational way by everyday people he encounters. the story (& therefore the process of filmmaking) is determined by the villagers he interviews. it’s an extraordinary piece & i think it’s very relevant to what we’re exploring here.