Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Lauren Russell

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Lauren Russell, author of Descent.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Lauren Russell

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Tarpaulin Sky author Lauren Russell, author of Descent.

Lauren Russell’s Descent (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2020) works to unearth the pulse beneath history. Here, research gives way to a polyvocal narrative of her ancestors, challenging the versions of history she has been handed down from family and her own education. Audre Lorde wrote, “In the cause of silence, each of us draws the face of her own fear- fear of contempt, of censure, or some judgment, or recognition, of challenge, of annihilation. But most of all, I think, we fear the visibility without which we cannot truly live.” Descent wrings a stunning vocality from the garments of our whitewashed history while simultaneously revealing the persistence of solitude tied to both omission and visibility. In this space, though, inquiry does not seek closure. Beneath historical narrative is detail, imagination, and memory – the fabric of mythology. Weaving through past and present, archive and diary, personal narrative and contradictory information, Russell speaks to familial erasures to answer the very necessary question: Who owns the past?

Excerpt from Descent:

Peggy:

The night before my water broke I dreamt

I bore a chimney babe into the world.

The cord it swung from her brick neck and ash

was streaming down her leg. Flames swaggered, reared,

charred her skin, hot poker hands unwound

her shift. I woke ablaze, my petticoat

drenched, roped his stiff beard round my neck,

and “She won’t work in no white man’s damn kitchen,”

I said. That beard reeked gunpowder, whiskey, Pris.

(31)

***

Tarpaulin Sky: Descent not only contains primary records but also documents aspects of the gathering process: your extensive journey to meet with and talk to extended family members or the travel and time taken to immerse yourself in different archives. You situate yourself in this context:

I am writing into the silences, the omissions, what has been left out either intentionally or because by its nature it defies legibility. I am writing into the space where one story trails off and another begins, oddly muddled… or within what only I imagined, bent over a photocopy of a photocopy of my great-great-grandfather’s diary and a stack of books and records…” (8).

As readers, we get to know the narrator as an adult who is deeply invested in this investigation. So our first question centers on how family history was passed down to you as a child. Did you grow up with old photo albums and storytelling? Or were there a lot of “silences” and “omissions” around your family’s past? How did family mythologies or their quiet absences shape your sense of self or your curiosity? It’s clear how much effort it took just to transcribe your great-great-grandfather’s diary- were you drawn to documenting your own life through journaling as a kid?

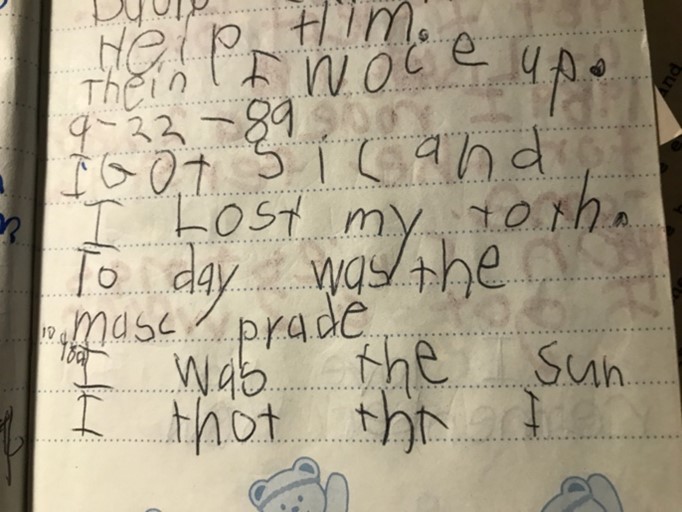

Lauren Russell: I have always wanted to be a writer, and I started keeping diaries from the time I was six years old.

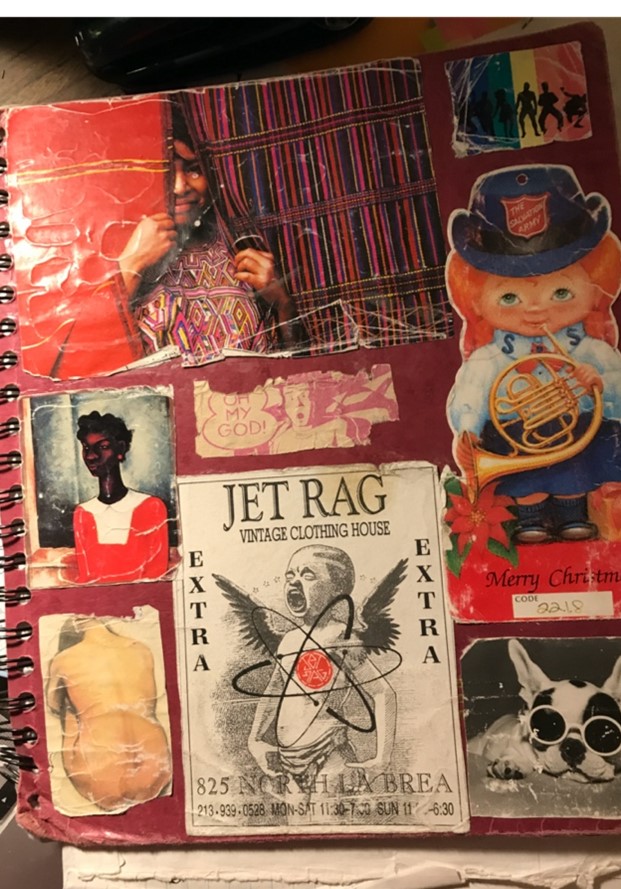

Later, when I was a teenager, they transformed into “notebooks”–less diaristic in nature but a mod podge of scraps of writings and drafts of poems and lists and notes, which is how I still notebook today (though without the collaged covers.)

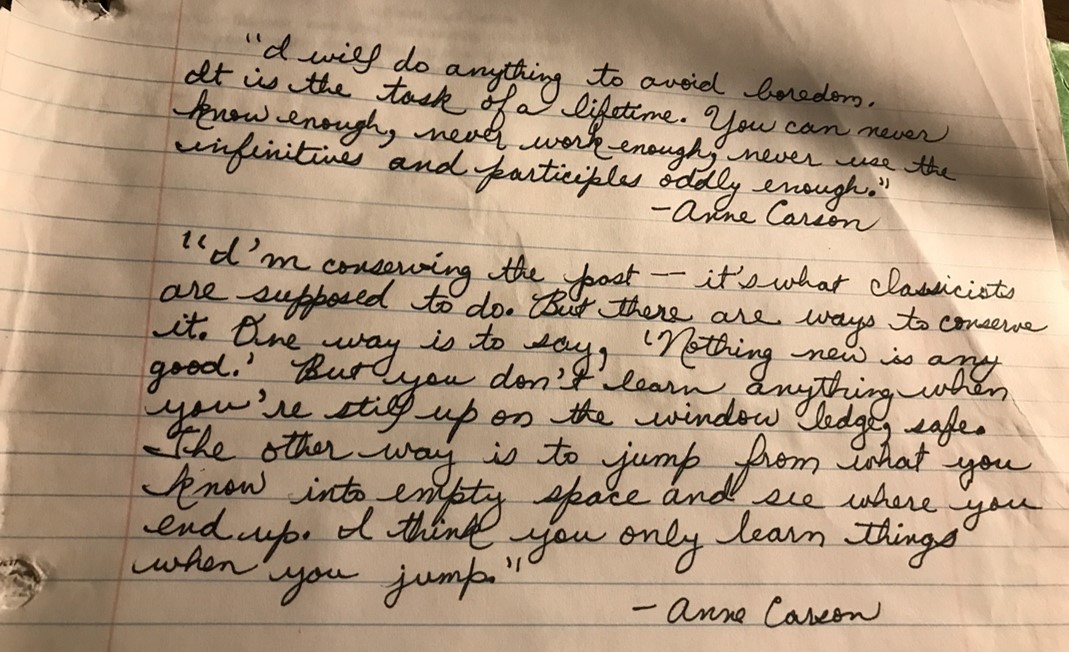

I started doing this after I read an interview with Anne Carson in Poets & Writers where she talks about not keeping things separate. I haven’t repurchased that issue (from March/April 2001; I am now very tempted to try to track it down), so this is all based on memory, but when I remember it now, I think Carson meant that she doesn’t keep her practice as a Classicist totally separate from her practice as a poet but lets them merge in the imagination. In my 17 year-old mind, I just internalized the idea of keeping one notebook for everything.

I kept scrapbooks for years (I stopped probably around the time I started grad school), and I wrote down a couple of other Anne Carson quotes, though not anything about her notebook:

I interviewed both my paternal grandparents the summer I turned 13. I believe it was at my parents’ urging. There is a Mormon lineage on my mother’s side, and though my mother was raised Congregationalist and I was raised Episcopalian, we have inherited the Mormon enthusiasm for genealogy. My grandparents, who were then in their late eighties, were uncomfortable with a tape recorder, so I took notes by hand. Based on these interviews and subsequent conversations, I wrote up each of their life stories. My parents must have taken them to a copy shop, as they had several copies made and spiral-bound. I remember presenting my grandmother’s to her shortly before she died that January, though now, curiously, I can only find my grandfather’s life history.

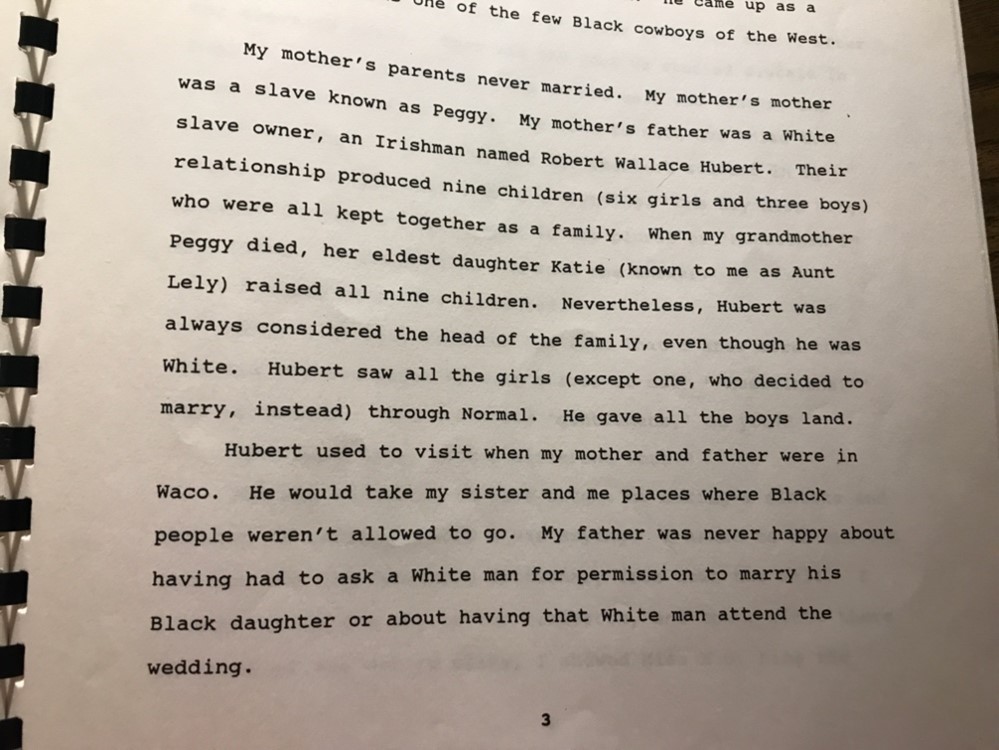

What my grandfather said about his maternal grandparents, Robert Wallace Hubert and Peggy Hubert, as captured in this account, is quite different from what I learned once I started investigating. For one thing Hubert wasn’t an Irishman. My grandfather also told me that Bob Hubert “took up” with Peggy’s sister Priscilla after Peggy died, which turned out to be untrue; when I started looking at census records, it became pretty clear that he was having children with the two sisters simultaneously. Interestingly Priscilla isn’t mentioned at all in the spiral-bound narrative.

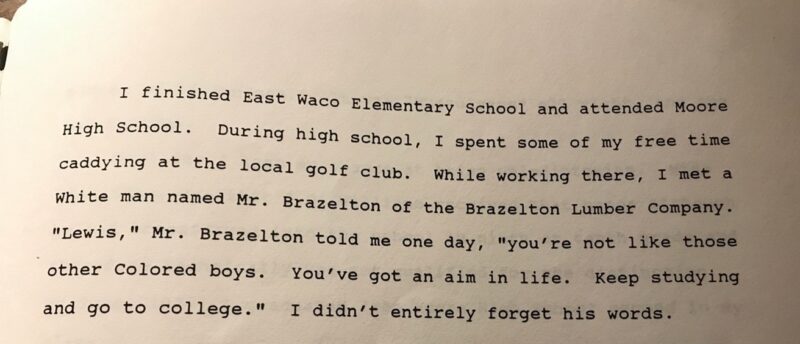

Grandpa also talked about a “Mr. Brazelton” he caddied for in Waco, who later had a major impact on his life, so when I encountered the name Brazelton on the signed verdict authorizing Jesse Washington’s execution (though not his lynching), different parts of the story began to converge in unexpected ways. The line “You’re not like those other Colored boys” kept reverberating in my head.

P.S. I found the Anne Carson notebook reference I mentioned. It was about a year earlier than the Poets & Writers interview I was thinking of, which makes more sense as far as when I started adopting this notebooking practice; I would have been 16. And it’s in The New York Times Magazine. You can tell a lot about my upbringing that my Los Angeles-based parents would subscribe to the Sunday New York Times, in addition to the daily Los Angeles Times. I think they still get three print newspapers.

From the article by Melanie Rehak, auspiciously called Things Fall Together:

“I write in notebooks, and I write everything in the same notebooks, academic stuff and footnotes and poetry, which is a mess because you can’t find anything,” she explains to me. ”But on the other hand, if I have a page with some little phrase I’ve thought up and then a quote from an ancient Greek poet and some other comment from a philosopher, it can all come together, and get pressed like veggie pate. You have your carrots and your broccoli and it all gets squished together, and it comes out very attractive.”

TS: Descent is, in part, a diary of your great-great-grandfather, as well as letters, records, research and your own interplay with these texts. In the beginning, you both resist and complicate mythologizing immediately. On page 8, you touch on Audre Lorde’s term for writing biomythography, which is the combining of history and personal biography in order to give more representation to multiple perspectives on a single narrative. One form that stands out in Descent is the persona poem. Throughout this collection, we read persona poems that embody voices of ancestors like your great-great-great grandmother Peggy, who lived through enslavement and emancipation. The poem “Peggy,” for instance, captures visceral fear on the eve of childbirth:

The night before my water broke I dreamt

I bore a chimney babe into the world…

I woke ablaze, my petticoat

drenched, roped his stiff beard round my neck,

and “She won’t work in no white man’s damn kitchen,”

I said. That beard reeked gunpowder, whiskey… (31)

These persona poems give me a chance to reflect on something you wrote early in the text. You say, “I would like to invoke Audre Lorde’s term ‘biomythography’ and puncture its seams, pull out its hem, and make ‘biomythology’ from the swaying threads.” Puncture is such an active word. This book not only dives into gaps in the narratives of your female ancestors but also actively works from the ground up, poking holes in the overarching narrative of your family established by this diary, which works like a mirror of narratives white people have created about Black history and Black people’s lives in America. Here, the use of different poetic forms amplify more voices, disrupting this history of silenced narratives. Could you talk about what biomythography means to you and how you came to the term biomythology? How do you think persona poems embrace or engage biomythology?

LR: Like many queer women of color, I read Audre Lorde’s biomythography Zami: A New Spelling of My Name in my twenties, and I thought of that book as akin to a memoir, but by coining this term “biomythography,” Lorde blurs the line between autobiography and mythology. Narrativizing one’s life is an act of self-mythologizing no matter what you call it, which I pointed out in a “complete bio” I was asked to write when my first book came out from Ahsahta Press. You can’t find it online anymore since Ahsahta went under, but I wrote, “As I struggle to write a ‘complete autobiographical statement’ at the urging of my editor, I am thinking about my resistance to autobiography, how much spin is involved in framing a life. When people ask me about myself, I always try to deflect the question. How much this is linked to shame.” I sometimes struggle with basic conversation because I just hate answering questions about myself. I mostly only want to talk about ideas. (Here’s an idea: Imagine a speed-dating event where everyone is required to read the same poem or book or passage beforehand or to watch the same film, and you are all also given a few specific prompts or questions to think about as you’re reading or watching, and then when you arrive you have a 15-minute conversation about the reading or film with each person, and at the end of the night you make a list of the people whose thinking attracted you the most. Nobody ever has to answer a question about their job or education or place of origin or how many siblings they have—most of which is Googleable anyway. I’d sign up. Especially if it didn’t actually require talking, like if I could have these conversations via instant messenger or email. If anyone is game, this interview can be your first text. I’m between 47% and 53% serious.)

Anyway, after Descent came out, there was a news item on the Poetry Foundation’s blog, Harriet, called “Lauren Russell’s Descent Riffs on Audre Lorde’s ‘Biomythography.’” The blog was quoting an interview I’d done for the Poets & Writers “10 Questions” series, where I said, among other things, that “my limitations as a researcher have created openings for imaginative work. Hence I call Descent a work of biomythology, a riff on, or expansion of, Audre Lorde’s ‘biomythography.’” At the very bottom of the blog post, the Harriet staff noted that Lorde discussed her concept of “biomythography” in Conversations with Audre Lorde. I was kind of alarmed when I saw this because I had never read the conversation in question and wondered if I’d been misunderstanding Lorde all along! I tracked down the book recently, and if anyone’s following along, this is in “Poetry and Day-by-Day Experience: Excerpts from a Conversation on 12 June 1986 in Berlin.” Lorde says (referring to Zami):

If I call it a biomythography and not a novel, although it is for me fiction—narrative prose—that’s because it embraces so many genres, certainly autobiography, but also history, mythology, psychology, all the different channels through which we, in my opinion, absorb information, process it, and create something new. Though much of Zami is autobiographical, it is not an autiobiography…. (155)

So I guess my initial understanding was not far from Lorde’s conception. I thought of Descent as fundamentally different from Zami, though, because Lorde knows what happened in her life, at least from her own perspective, but with Descent, there was so much I could never know. I am most interested in the mythologies we create around what is unknowable. There is my great-great-grandfather Robert Wallace Hubert’s self-mythologizing through his diary, there is the way my grandfather and other members of my family have mythologized Hubert as an almost heroic figure, which I find fascinating and am intentionally disrupting, there is my own self-mythology/research narrative in the form of lyric essays throughout the book, and there is a biomythology of my great-great-grandmother Peggy Hubert I’ve created precisely because her life remains so undocumented. So, for instance, in the part you quoted: my grandfather told me that Bob Hubert said he educated his daughters because “he didn’t want them working in no white man’s kitchen, ’cause he knew what would happen then,” which I reference in “Ceremonium Morteum” on page 80. I always thought this was quite telling, given that Peggy was Bob’s cook. I flipped it for Peggy’s retelling, with her saying, “She won’t work in no white man’s damn kitchen” the night before she gives birth to her oldest daughter, Laly. This is a rare place in the book where I have Peggy say something that, historically, I do not believe she would have said. But my Peggy is outside history, so just this once, she can say it. As I write near the end of the book, “I know that my Peggy is no approximation of the real Peggy,” but my Peggy has become real for me. That’s biomythology.

Since you are tracking persona poems, you may have noticed that Peggy speaks in iambic pentameter. I happened upon this approach when I was auditing a forms class with Jeff Oaks at the University of Pittsburgh in the spring of 2014, when I was just starting to write poems toward the manuscript that would become Descent. We had just read some poems in iambic pentameter, including Marilyn Nelson’s poem “Churchgoing,” where the speaker reckons with practicing a religion that, for our ancestors, was entangled with slavery. The class had the assignment of writing a poem in blank verse, unrhymed iambic pentameter, and I wrote an early draft of the first poem in Peggy’s voice, which appears on page 12. Jeff pointed out that blank verse was a great fit for this voice because it has the constraint of strict meter without the prettiness of a rhyme scheme, and I also found that the meter creates an interesting idiosyncratic voice, so I stuck with it.

Later, when I was at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as a fellow, Amaud Jamaul Johnson suggested that I organize my research by keeping three notebooks—one for images, one for diction, and one for narrative facts. For the persona poems in particular, the diction notebook was key. As I was reading through oral histories of formerly enslaved people in Texas, I’d notice interesting turns of phrase that I’d write in the “Diction” notebook, and iambic speech tended to jump out at me. I wound up putting some of those fragments from oral histories in Peggy’s mouth, as I explain in the Notes at the end of the book. For instance, “Since Freedom, I been through the toughs” is from Rosina Howard or Hoard, depending on which transcription you reference, and “the burst of freedom came in June” is from Sarah Ashley. Both of them were born enslaved and might be surprised to know that they were making poetry when they gave their oral histories for the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s. The only changes I made to their marvelous phrasing was to change “I’s been” as recorded by the Federal Writers Project to “I been” and the tense of “come” to “came.” This is also biomythology.

Your description of Descent as a “mirror of narratives white people have created about Black history and Black people’s lives in America” makes me think of John Keene’s Counternarratives, which is one of the best books I’ve ever read. Actually I don’t think I deserve to be in the same sentence as Keene. Everybody should be reading that book! I read Counternarratives later in my process, so I was not thinking of the concept of counternarrative all the way through as I was with biomythology, but that’s definitely another frame through which to think about it.

TS: The way you arrived at Peggy’s voice is really inspiring because, like the notes section of this book, your description shows how your writing community and reading are a part of the project of mythmaking. I am glad you brought up the “self-mythology/ research narrative” woven in with the persona poems, photographs, and research you’ve done. What I love about these prose parts is their ability to create a thread through the other stories told through different lenses/ genres of storytelling — some via poems, some spoken through photographs included in the text. The experience of reading Descent feels very much like the research lives with both the writer and the reader, creating links, pauses, tangents, and more questions. On page 15, we’re introduced to your profession as a writing teacher, and then travel into scenarios where you ask vital questions about yourself and your own history. In the following pages, you are alone at the beach, in therapy, and reading articles in the Smithsonian traveling through time and space, posing questions about the past. “Do moments build, or do they amass?” is a question that, to me, gives freedom to the use of all these lenses – particularly the prose. Which makes me realize that the prose in this book is composed of different styles or maybe genres (depending on how much one might want to parse prose writing, I suppose): documentary writing, poet’s prose, personal narrative, essaying. Once you started writing persona poems, how did you decide on lyric prose as the carrier of narrative arc? In part, this question is driven by something Lyn Hejinian said in The Language of Inquiry: “Prose is not a genre but a multitude of genres.” Here, she is referencing how prose continues to evolve, how it resists nostalgia in its consumption of other genres or style. And maybe that is linked to inquiry — how a narrative consumes information but does not necessarily solve the questions tidily or completely. For you, how does prose engage in a writer’s ability to capture identity?

LR: I haven’t read that Lyn Hejinian book, but now I’m going to check it out. Can you do me a favor and tell me which essay you’re quoting, so I can find it more easily than the conversation the Harriet staff was referencing in Conversations with Audre Lorde? What you’re saying reminds me of the chapter in Ulysses where Joyce writes in about 20 different prose styles, imitating everything from the Anglo Saxon to his own contemporaries. It’s such a grand takedown. I’m a descendant of the Modernists as far as their use of collage, pastiche, taking anything from anywhere. There is also a sense of entitlement in it. What would it mean for a woman of color to do what Joyce did, to declare through style and form, “I have a right to all of this”? Would the stakes be different?

Before reading your question, I would not have made any distinctions among the prose except for the fundamental one between the prose poems and the lyric essays. But now that I think of it, the three essays I think of as forming the narrative arc of the book are the self-mythologizing ones that probably prompted Tarpaulin Sky to classify the book as Hybrid/Poetry/Memoir, when I would have thought of it as Hybrid/Poetry/Essays. These three essays are dated with the location of composition: The one you’re describing was written (or at least drafted) in Maui on January 1, 2015, and the second one, which begins on page 49, I wrote in Madison, March 7, 2015, which is significant because Tony Robinson was killed in Madison the day before, and the last essay, the penultimate piece in the book, is split between Madison, December 19, 2015 (written in present tense), and Pittsburgh, September 22, 2016 (written in future tense). There is not much about research in those essays, but they show me grappling with what Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlife of slavery” in the 21st century. Though I wrote the essay that starts on page 67, about my trip to Texas, soon after I got back in the summer/fall of 2015, the rest of the straight research essays came later, in 2017 and 2018. I didn’t provide any dates or locations for those; they’re not really part of the three-essay arc.

I may have a note about why I decided to create that arc somewhere, but I have yet to dig it up. I remember that it was during or right after my fellowship year at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and at the time I was vaguely thinking of moving to Austin, which I ultimately determined was impractical since I had no job lined up there—but in my original conception that third essay would have shown me relocating to Texas in a sort of reverse migration from my grandparents’, which would have turned it into a different story. Where I actually wound up going after Madison was (back to) Pittsburgh, specifically for a job as Assistant Director of the then newly-formed Center for African American Poetry and Poetics at the University of Pittsburgh, and the question that kept coming into my head—“What would Peggy think of this?”—created a different kind of arc. What also runs through all those essays is how I’ve been cohabitating with loneliness everywhere I live, and how that connects me to Bob and to Peggy, and how solitude has also provided me with a degree of autonomy and freedom that Peggy probably could not have imagined. I have come to think of loneliness as a creative collaborator.

TS: The Hejinian essay is called “A Thought Is the Bride of What Thinking.” The book The Language of Inquiry is a series of essays and lectures she has given opening up the notion of how prose works or can work. You’ve really got me thinking about what it means that loneliness is your creative collaborator, as you say. I noticed that loneliness is a tendril throughout Descent. Biomythography helps you to capture loneliness, or perhaps just give a glimpse as to what loneliness may look like in others across generations, across class divides. I think this is one of the ways it moves beyond the instinct to conserve the past when portraying history. There is “cohabitating” with loneliness that you mention, appearing in moments like:

“One autumn in New York I was so excruciatingly lonely that I could imagine loneliness driving a person to do something desperate. Loneliness a kind of agony. The last lines of a magazine poem Hubert copied into his diary: “What is home with none to meet, / None to welcome, none to greet us. / Home is sweet, and only sweet,/ Where there’s one who loves to meet us!” I want to tell him to get a cat, as I have. (15)

Yet, you also expose major differences among the lonely. For some, it is solitude. Solitude can be a consequence of the fight for autonomy and agency as a Black woman. One particular moment that comes to mind is when this is said: “I wonder at my solitary life—how I’ve blown myself to the four winds without a map or compass just to be a woman who owns her own person” (16). Much later in the book you circle back to this same sentiment, “I own my own body: my hands, my hips, my cunt, my unruly black and white curls frizzing in the wind. And out of my loneliness I am making—what?” (92). These instances echo back to other enslaved as well as freed Black ancestors, like Peggy, who were written out of family records and couldn’t own or control their historical representation. What guided your decision to include resonances of your “solitary” life among the history of your ancestors? What did you discover/learn from writing about loneliness from an intergenerational perspective?

LR: Thanks for pointing me to that Hejinian essay. I love her term “exuberant uneasiness” (8). I have pretty serious OCD, and my particular subset of OCD is called “moral scrupulosity.” Since childhood I have worried obsessively about causing harm to others and of not preventing harm if that might be a possibility, which can make ordinary decision-making an agony. Something I’m trying to work on in therapy is becoming more comfortable with moral ambiguity and with not knowing. It is a state of existing with, in, and alongside uneasiness—but it is only on the page that uneasiness may become exuberant. My poet friend Chris Martin has written something to the effect that for people who live anxiously, poetry can be a place to explore, experiment, and take risks safely. In an essay in the Alaska Quarterly called “Autism, Poetry, and the Art of Transformation,” Chris writes,

My students, for whom change is frightening, seem miraculously to thrive when facing change head-on in their poems. It’s as if imagination works as a leavening force against the real, causing its cold sharp edges to soften and warm. Within the safe, circumscribed, and playful field of the poem, transformation can be a territory that is explored, lightened, and, somehow, transformed itself.

Thus poetry is a real site of possibility.

The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to widespread isolation as well as mental health crises. It exacerbated my OCD and my loneliness. For someone who is obsessively afraid of causing harm or potentially killing someone, the pandemic created a situation where the only way to know I was not killing someone was never to interact with other human beings in person. I really didn’t for the fourteen and a half months from the escalation in mid-March of 2020 until I was fully vaccinated in early June of 2021—except in essential ways I could find no way to avoid, like when my garbage disposal broke and caused the dishwasher to flood my apartment, and even then while the technician was fixing the garbage disposal, I was hiding in the next room, masked with the door closed. The bigger challenge was when I accepted a position on the faculty of the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities at Michigan State University and directorship of the RCAH Center for Poetry at MSU. I was excited about the job but overwhelmed by the prospect of relocating from Pittsburgh to East Lansing in the summer of 2020, while the pandemic was raging. I am so afraid of killing someone that I have never learned to drive, but a friend was kind enough to take me. (We were both masked, with the windows rolled down, and I was also wearing a face shield attached to a cap, but still I was worried about the possibility of making her sick.)

I am writing a long abecedarian list poem called “Moral Scrupulosity: OCD,” which is basically a catalog of my obsessive worries and the compulsions they produce. I’m not sure anyone will want to read it, I don’t even want to write it, but maybe if people understood what it is like to live with this, they would be a little more generous to one another (because we can’t know what those around us are experiencing), and also stop using the term “OCD” casually. Relocating during the pandemic with severe OCD created the conditions for a kind of extreme isolation that, even for someone accustomed to loneliness, was beyond anything I had experienced before. This experience, and the formal autism spectrum diagnosis I received in March of 2020, have changed how I think about the loneliness I live with—but all of this happened since writing Descent.

To answer your question, I started writing about loneliness in Descent because A.) Nearly all my writing is about loneliness even when it is “about” something else; and B.) When I read Bob Hubert’s diaries, I connected to his loneliness through mine, and that initial recognition made me uneasy (and not exuberantly so).

I am interested in what you are saying about loneliness as experienced across socioeconomic divides. I recently read Fay Bound Alberti’s A Biography of Loneliness, where she makes this point:

While the positive benefits of loneliness might be linked to the natural world and to the benefits of artistic creation, these experiences are not available to many socio-economically deprived individuals. … Like the concept of slow food, self-care and self-improvement is class-based and dependent on mental and physical capacity as well as time. (237)

I am one of the privileged lonely, and while I certainly did not and would not choose to have OCD, I was able to survive for over a year with almost no in-person human interaction because I was working from home and could afford to get everything I needed shipped or delivered to me. If I’d had to go out regularly during the pandemic—as so many other people did—I probably would have obsessed about causing harm to the degree that I would not have been able to function. Even as it was, I found my weekly trips to the mailroom of my apartment complex stressful. So while I am considered “successful” in my professional life, that “success” is precariously achieved only through the great difficulty of managing chronic mental health challenges, and that management is only possible with the help of others—and sometimes, as in the pandemic, even on the backs of other people I have never seen, people risking their own health and safety daily while I was hiding out with my anxiety. The self-mythologizing sentence you quote is a bit of a lie. I may have blown myself to the four winds without a map or a compass, but unlike most people I know, I have always had the safety net of the upper-middle classes.

In A Biography of Loneliness, Alberti discusses the loneliness of homelessness and the loneliness of refugee experience, and how this is fundamentally different from the privileged loneliness of the artist in his (historically more often “his” than “hers” or “theirs”) proverbial garret, and how the essential difference is choice. While I appreciate that distinction, I am not positive I agree with the choice element in my own case of privileged loneliness; it’s more complicated than that. I don’t know how much loneliness is a state I have adapted to and learned to create through precisely because it has never felt like a choice, and how much I have chosen loneliness as the price I have to pay for poetry and a certain degree of autonomy. Regardless of what narrative I tell myself, in the end, loneliness remains a site of reckoning.

Alberti discusses the loneliness of widows and widowers not unlike Bob Hubert, but she never takes up the loneliness of chattel slavery. Can you imagine the unutterable loneliness of being sold away from family and friends, forever, and of living with the knowledge that this could happen at any time? My grandfather Lewis Russell’s maternal grandfather was Bob Hubert, the slaveholding Confederate officer of Descent. But my grandfather’s paternal grandfather was the first Lewis Russell, a Black cowboy who was born enslaved. Grandpa told us that the first Lewis Russell’s last memory of his mother was of clinging to her skirts as she was led away from the auction block. He was about five years old at the time. How can I imagine a loneliness that vast?