James Pate’s Evening Signals

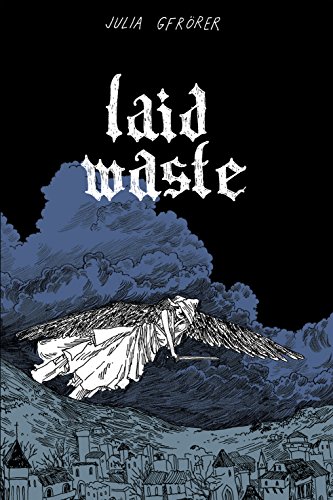

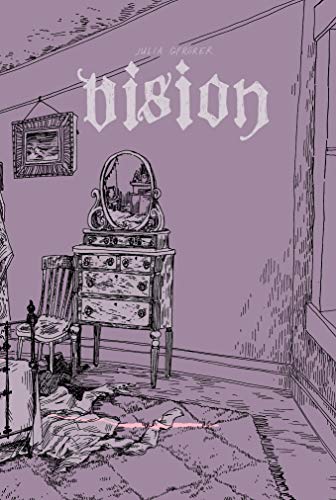

Angels of death, mirrors, and graphic novels:

Two gothic titles from

Julia Gfrörer

Evening Signals is a column by James Pate exploring the Baroque, the Gothic, the Weird, and the Fantastique in contemporary poetry and fiction.

James Pate’s Evening Signals

Evening Signals is a column by James Pate exploring the Baroque, the Gothic, the Weird, and the Fantastique in contemporary poetry and fiction. Investigating angels of death, mirrors, and graphic novels, Pate explores two titles from Julia Gfrörer: Laid Waste and Vision.

Possible spoilers included

There’s a certain type of Gothicism that is not frenetically-paced or particularly plot-driven, but, in its very refusal to move the story along, creates an undercurrent of dread and foreboding. Often, there’s a historical element at play, with the story being rooted in the past, or in a present that doesn’t feel especially “present,” and scenes sometimes have a playing-out-in-real-time quality. Novels such as Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and Elizabeth Engstrom’s Black Ambrosia and films such as Dreyer’s Vampyre, Herzog’s Nosferatu, Feigelfeld’s Hagazussa—such works exude a bleak lyricism due to their almost naturalistic approach to horror. Here, the otherworldly seeps out from the quotidian, and stillness is as powerful as action. Julia Gfrörer’s graphic novels Laid Waste (Fantagraphics, 2016) and Vision (Fantagraphics, 2020) seem to share this approach to the Gothic. The narratives in both are amorphous and hazily-edged, so that they seem less like plotted works and more like daydreams unfolding. Drawn with fine, intricate detail, and eschewing color in such a way that they seem to take place in a shadowy and stark terrain, the books are uncannily open-ended. They make it clear we’re only catching glimpses of the lives of these characters, and that sense of presence/absence haunts what we do see.

Laid Waste is a story of a village devastated by plague. The village is unnamed, and no year is mentioned, but the setting suggests this is during the time of the 14th century bubonic plague. The tale opens with a prologue. A young mother is beset by a vision that may or may not be a dream. Two visitors—an angel of death (with bird wings seemingly coming from the sides of the figure’s head instead of the figure’s back) and a grim reaper (whose hood is down, revealing a skull wearing a crown)—approach her, and attempt to persuade her into letting them take her child, promising her they will keep the child safe from want. The mother then wakes up, or comes to, and realizes she is no longer holding her child. In one of several time jumps in the story, we learn that the infant has been buried. The mother digs up the body and, in another time jump, we see the child now as a young girl. In the frame, unattributed voices talk about how she, the child, doesn’t remember what happened. This brief episode is never explained in the rest of the graphic novel, and, in fact, is only obliquely referred to later on (the infant, Agnes, will appear to be immune from the plague as an adult), but it establishes not only the atmosphere of the novel (how these characters are haunted by death and otherworldliness) but its fragmented, elliptical narrative style.

Laid Waste is a story of a village devastated by plague. The village is unnamed, and no year is mentioned, but the setting suggests this is during the time of the 14th century bubonic plague. The tale opens with a prologue. A young mother is beset by a vision that may or may not be a dream. Two visitors—an angel of death (with bird wings seemingly coming from the sides of the figure’s head instead of the figure’s back) and a grim reaper (whose hood is down, revealing a skull wearing a crown)—approach her, and attempt to persuade her into letting them take her child, promising her they will keep the child safe from want. The mother then wakes up, or comes to, and realizes she is no longer holding her child. In one of several time jumps in the story, we learn that the infant has been buried. The mother digs up the body and, in another time jump, we see the child now as a young girl. In the frame, unattributed voices talk about how she, the child, doesn’t remember what happened. This brief episode is never explained in the rest of the graphic novel, and, in fact, is only obliquely referred to later on (the infant, Agnes, will appear to be immune from the plague as an adult), but it establishes not only the atmosphere of the novel (how these characters are haunted by death and otherworldliness) but its fragmented, elliptical narrative style.

The story moves forward several years, starting in medias res with the plague already raging. Agnes speaks to her dying sister, who is drawn in some panels to look almost beatifically at peace, with a wan smile and kind eyes, and in others like a corpse, with shaded-in cheeks and empty eyes. (The scene of the two sisters together is visually evocative of Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, where a recently deceased woman speaks through her corpse to her sisters.)

We learn in the scene that Agnes has lost her husband and children to the sickness (the protagonist in Vision will be a widow too), and that, in losing her sister, Agnes’ last familial tie will be gone. The story will focus on what Agnes does with her life after these devastations. She’s drawn to both the corpse heap, literally, and to the possibility of beginning a new life with a recent widower.

Gfrörer’s style in this book and in Visions is to employ a consistent paneling (each page in Laid Waste has four frames, and, in Visions, there are nine per page) and she doesn’t use splash panels. The effect of such consistent framing lends a rigor to the novels—even the dramatic moments are kept evenly paced and on the same visual scale—and it also adds to their fragmented quality, so that we never get the larger, more encompassing view we might expect with a splash page. The style increases the Gothicism in the novels. What we don’t see adds tension to what we do see. And we continually sense there is something teeming and inexplicable just outside the edges of the frames.

Laid Waste does not provide us with the story of the village as a whole: there are no town meetings, no scenes of village leaders wondering how to deal with the crises. The novel suggests we’re already beyond such narratives. The center no longer holds. What we do see of Agnes’ village is that it is a place that has imploded. Dogs snarl over human limbs. The plague doctor turns out to be just as vulnerable as the other characters. Bodies are tossed upon more bodies with little to no ceremony. Yet Agnes still scrapes out a form of meager, melancholic life.

The cover illustration of Laid Waste shows an angelic figure of death over the village, their huge wings shaded to look like a vulture’s. They hold a sword over the village, and yet they also have an arm raised over their face, covering one of their eyes as if to shield themselves from the despair they are causing. It’s an ambiguous image, sinister and sorrowful by equal measures. And it’s a powerful representation of the novel as whole, where even the end—which might from certain angles appear to be mildly happy—is not of the triumph-of-the-human-spirit variety so popular in the U.S. today. The human figures walk out of the frame, and the final panel is an image of graves, an empty church, and mountainous clouds.

Gfrörer’s Vision takes place in the nineteenth-century and involves Eleanor, a widow, and her claustrophobic relationship to her brother and sister-in-law. In such a patriarchal society, Eleanor is trapped, forced to take care of her ailing sister-in-law by a brother who refuses to hire a maid, and who tells Eleanor bluntly that things would be different if her husband hadn’t passed away. Eleanor finds two outlets from such pressure. One is through cutting, the bleeding from which she staunches with a black handkerchief she used for her father’s funeral—an act that is Poe-like in its blend of grief and abjection. The other means of release is through the romantic/erotic relationship she has with her haunted mirror.

Gfrörer’s Vision takes place in the nineteenth-century and involves Eleanor, a widow, and her claustrophobic relationship to her brother and sister-in-law. In such a patriarchal society, Eleanor is trapped, forced to take care of her ailing sister-in-law by a brother who refuses to hire a maid, and who tells Eleanor bluntly that things would be different if her husband hadn’t passed away. Eleanor finds two outlets from such pressure. One is through cutting, the bleeding from which she staunches with a black handkerchief she used for her father’s funeral—an act that is Poe-like in its blend of grief and abjection. The other means of release is through the romantic/erotic relationship she has with her haunted mirror.

The theme of the mirror is often explored in Gothic literature and film. From Valery Bryusov’s “In the Mirror” to the infamous last scene of the second season of Twin Peaks, and through many other examples as well, the mirror harbors occult possibilities. The reflection multiples selves, rooms, walls, windows. The mirror is an eerie rendering of the line (often attributed to Paul Éluard) that “There is another world, and it’s this one.”

In Gfrörer’s graphic novel, the first voice we hear is the mirror’s as it speaks to Eleanor. “Look at you,” it says. “Just look at you. You’re stunning. Perfect.” It’s the mirror doing the looking. Because the words are rendered in bubbles that are neither in the speech or thought bubble style, who/what is saying them is unclear, though they are clearly addressed to Eleanor, who appears in these opening frames. At first, this uncertainty might lead the reader to think that the mirror’s voice is actually Eleanor’s interior monologue. Yet as the story continues, the mirror’s otherness to Eleanor increases, suggesting Eleanor is not simply projecting on to the mirror (or, if it is Eleanor’s unconscious, it’s on such an inner level that it basically becomes Other). Jealousy, estrangement, hurt: whatever haunts the mirror is as fragile, and as capable of lashing out, as the human characters in the story.

And what does haunt the mirror? Possesses it? In some scenes, the mirror-specter seems to be ageless and anonymous, claiming that it knows everything about Eleanor. In other scenes, we glimpse an ill-defined shadow in the glass, suggesting that this entity is specific—a ghost with its lingering sense of self—and maybe the phantom of Eleanor’s late husband Harry. That such different readings are allowed in Vision without one canceling out the other creates a multi-layered dynamic within the narrative. Each version of the story haunts the others.

Twin Peaks: Season 2, Episode 22

The mirror is also a portal. In one of the novel’s most surprising passages, Eleanor, upset at being left by the mirror-spirit, pushes herself through the looking-glass. (She has recently ingested laudanum, and it’s possible her experience is at least partially induced by the drug.) She doesn’t enter into a wonderland of reversals and playful surrealism, but into a seemingly cosmic space that at time seems like the night sky (there are tiny white flecks in the darkness that could be stars) and at other times like an image of what is sometimes called darkness mysticism (the dark squares being a representation of the unpresentable, the ineffable—a vision). Mystics such as Angela of Foligno and Pseudo-Dionysius employed the concept/image of darkness as an element of the divine, and Eleanor seems to be partaking in a similar experience.

How this moment is conveyed in the actual drawing is also unexpected. Instead of showing simply a splash panel of this dark space, each panel is kept the same size as the rest of the graphic novel, so that the darkness implies time passing/floating within this zone (as opposed to the instant-of-time a splash panel would have suggested). And the panels of dark ink are “there,” part of the materiality of the book itself, so that the fourth wall is broken here (or at least eroded) in the way the pages remind us we’re reading the book in our hands. The squares are also reminiscent of the passage in Robert Fludd’s 1617 The Metaphysical, Physical, and Technical History of the Two Worlds, the Major as Well as the Minor, where he illustrates the nothingness prior to Creation with a stark black square, around the edges of which are written Et sic in infinitum (“And so on to infinity”).

This moment echoes an earlier scene, when Eleanor is left in a dark room after a procedure on her eye, and foreshadows a later one, at the end of the novel. It’s an unusual move to allow so much emptiness and seemingly blank space to exist within a work, yet, to go back to element of open-endedness mentioned earlier, these moments in Vision fundamentally shape the reader’s experience of the narrative, causing the story itself to seem adrift and unmoored, as if these scenes (or anti-scenes) are an emptiness from which the characters temporarily awaken.

Gfrörer’s work in these two graphic novels is bleak in the extreme, but it’s not misanthropic or cynical. Her characters might live in an indifferent universe but not a cold one. The connection between Agnes and her sister in Laid Waste and Eleanor and the mirror in Vision are all the more intense due to their fleeting quality, and the way these connections unfold among such an enigmatic environment (did Agnes return from the dead? who/what is possessing the mirror?) increases the strangeness of the connections themselves. And unlike the type of Gothic narrative where the enigmatic clears away at the end (a move that often feels like a panicked gesture toward Realism), the plaintive opacity continues in these vivid stories. The characters live among the ruins, and they boldly refuse to pretend otherwise.

About the Author

James Pate has had work published in Heavy Feather Review, Oculus Sinister: An Anthology of Ocular Horror, Black Warrior Review, 3:AM Magazine, Deracine: A Gothic Literary Magazine, Ligeia, Coffin Bell, and Occulum, among other places. His books include The Fassbinder Diaries (Civil Coping Mechanisms), Flowers Among the Carrion: Essays on the Gothic in Contemporary Poetry (Action Books Salvo Series), and Speed of Life (Fahrenheit Press). His poetry collection Mineral Planet is forthcoming from Schism Neuronics.