Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Selah Saterstrom

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity—the gestation and development of these imaginings—focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Selah Saterstrom on her latest book, Rancher.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Selah Saterstrom

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity —the gestation and development of these imaginings—focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Selah Saterstrom on her latest book, Rancher.

Selah Saterstrom’s Rancher (Burrow Press, 2021) is a book-length essay which takes the form of a resurrection. Offering no diversions in the rigorous investigation of how to rest with the violence Saterstrom endured when she was young, the form of the resurrection gives way to an unseen community of women, girls, people who are not just survivors, but who are resistors. Rancher balances an inviting level of candidness with a formal syntactical style to examine why some sentences are believed and some people are not believable. Readers are first introduced to Saterstrom’s “not interesting” rapist, whose story is quickly overtaken by the transgressive laughter of ass-kicking schoolgirls from St. Maria Goretti, The Sound of Music, ever-constructive black widow spiders, prophets, saints, and martyrs weighing in on everyday life, and the sustaining conversations contained within friendship. As a resurrection, this essay is about the “terrible, smooth underbelly of ongoingness” of trauma and questions, “How do you solve a problem like Maria?” Like any resurrection, this essay takes place in the afterward of ongoingness, where the narrative of a violator simply cannot hold. After the laughter of violent men has died down, we are left with a more visible web of relationships: the love at work behind the words of this essay, the tender hands parting the dirt and unearthing us to breathe again.

Brief Excerpt from Rancher:

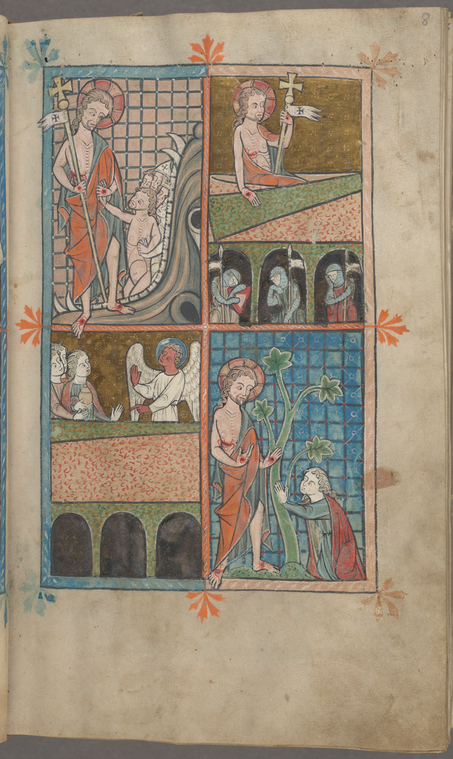

I can imagine writing as a Eucharistic event. In the mouth. In house. I can imagine a sentence which punches me in the stomach. Noli me tangere: touch me not. Words said by Jesus to Mary Magdalene when she encountered him post-crucifixion in a passage of writing considered to be some of the most difficult to interpret in the whole of the New Testament. The dominant prevailing historic read of Mary Magdalene is that she has a credibility issue.

Over twenty years ago, I spent four years studying and extrapolating this verse: the seventeenth of the twentieth chapter of the Book of John, the most Gnostic of the canonized gospels, and using acute stitches, relating my analysis to issues of proclamation rooted through Eucharistic traditions. The result was a 278-page (unpublished) monograph painfully titled, Noli Me Tangere: The Disbelief of Women’s Proclamations as it Relates to Eucharistic Celebrations and Bodily Sovereignty within Contemporary Hermeneutics. It is a book that outlines a feminist Hermeneutics of touching and reading, two gestures springing from the same root. For example, when a woman can’t touch the body of Christ (Noli me tangere), history bears out that in short order, she can’t touch the other great corpse: the Word that is God, the Biblical text. Which is to say, she is not allowed to read it out loud, by herself, within the church, with recognized authority. Which, in turn, stripped women of political rights and bodily sovereignty. Here we find ancient debates concerning women being able to control their own bodies (reproductive rights) as well as the (still, in many places) hotly contested issue of the ordination of women into the priesthood.

G/host. The old-timey story of how a ghost becomes a host (that, once in your mouth, turns back into a body). Words are haunted by bodies and bodies are full of words, which are also ghosts. It is this communion-juncture that so often undergirds the experience of writing for me.

I once asked Joan of Arc about not being believed. We were having a cigarette between shifts. “Listen,” Joan said, while sucking down a Virginia Slim. “Imagine screaming: I am on fire. Imagine your blood boiling. I’ll tell you what,” she continued, “I felt like goddamned Carrie at the prom free bleeding, the stigmata in overdrive, like having your period out of your eye balls or whatever.”

Imagine screaming in someone’s face, but the someone does not hear you. Imagine the isolation you might feel. You might begin to wonder if you are a ghost. And this is why no one can hear you screaming.

From somewhere else in this essay, my dead grandmother lights a cigarette in her orange Sears recliner and says that where her family was from in Scotland they had a name for that sort of woman, the Keening Woman. In her body she held the Spirit of Lamentation, and it was her burden to vocalize it on behalf of the village.

***

Tarpaulin Sky: While Rancher is a long essay, it begins with a poem that invokes basket weaving, being “amongst” friends, and ends with the assertion, “We will find a place where we can rest, / where a story can rest.” It reminds us that a resilient life is woven amongst friends, as though a collective ache can be shared when the people in our circles find resting places for our experiences, even the harrowing ones. Rancher asks readers to push their preconceived notions of what friendship is or with whom they can strike up camaraderie. You commiserate with Joan of Arc; discuss your writing with Larry, a spirit in your laundry room; dive deeply into the psyche of saints like Maria Goretti; share infestations of curiosity about black widow spiders with a friend in Denver; and reach out to friends across the country at the end of this piece to hear their perspectives on why anyone should write an essay about rape. These sustaining conversations also reveal your own childhood to have been a source of ache and learning. You explain, “Where we lived, there wasn’t enough of anything, including oversight, so rapers slipped in” (15). While it’s clear that various forms of kinship are essential to your writing practice now, I’m wondering how early friendships (with the living, dead, or non-corporeal) influenced your childhood. What did close relationships and conversations with others teach you as a child? Did they offer you any early resting places?

SS: Thinking of stories as places to rest, I immediately envisioned a wonderful daybed, a place, yes, to rest. Childhood had such places in spades—the stories were magnificent and humming with all the frequencies of the landscape, the living and the dead. Except also in the bed were knives (at least one). And bullets (several). And empty liquor bottles. Clanking about. And ghosts (one should avoid sharing a bed with ghosts). But surrounding these things: an opera of a bed!

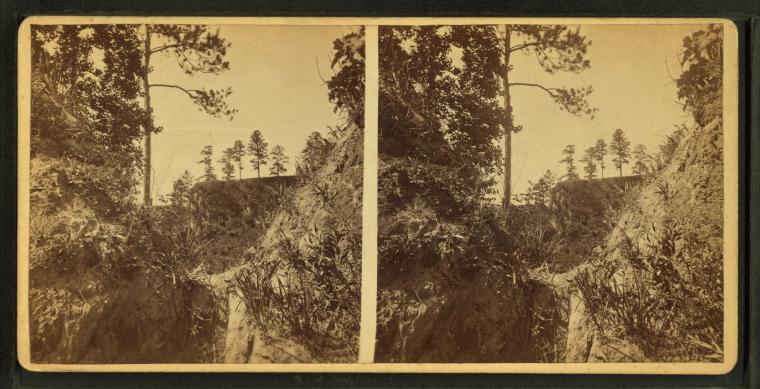

I primarily grew up in Natchez, Mississippi. For a portion of my childhood my mother and I (along with my sister and other aunts, uncles, and cousins) lived with my grandparents in an early 1800s rural farmhouse on the bluffs of the Mississippi River at the end of a dirt road—Cemetery Road, aptly named for the large 1822 cemetery nearby. The Harpe brothers (the earliest documented serial killers in the United States) were associated with this property, as was Jean Lafitte. The land adjoined the infamous bayou, the Devil’s Punchbowl, which was also the site of a post-Civil War atrocity wherein a concentration camp was established in its kudzu depths and there 20,000 freed slaves died. The Devil’s Punchbowl is also known for its wild peach groves, though no locals eat the fruit. I recall that in the early 1980s a puffy red-faced police officer came to my grade school and said not to go in it because it was 100% a Devil Worshiping Hell Hole (which is one way for a dominant white culture to pathologize the site of an atrocity it created and wished to continue controlling).

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Devil’s Punch Bowl.” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

When I told my sister I was writing about this place, we started exchanging memories and this went on for many days. She told me things I had forgotten or never knew, like the story of my grandfather, mother, and the shapeshifting panther. She reminded me of the time when middle-of-the-night visitors surrounded the house chanting a demand to know where the woman was. What woman? We couldn’t see these individuals, we could only hear them. My grandfather stood on the porch, a cigarette enjambed into the corner of mouth, shotgun raised, and responded into the pitch dark void of a sweating night that we had seen no woman pass by.

That is how it was—everything was shot through with so many, to use Kathleen Stewart’s phrase, animated strands of potential. The uncanny drift in which we were situated vibrated; the needle would skip across the surface of the record. Things were relational. Categories were punctured. As I experienced it, in every space, the conditions were hospitable to narrative because in every space there was the potential for emergence and the presence of juxtaposition, two conditions favored by both the disaster and the oracle.

Tarpaulin Sky: The bed you mention is such a fantastic and full image to turn over. I’m thinking about what rest means and how it has the potential to be a vessel or a container. Your response reminds me that conversations, loving relationships, and writing are all places of rest. They are the sites of acceptance where we can lay down our unaltered stories, free from the cultural impulse toward a tidy conclusion or moralized outcome. Past violence—all the ways that violence can shape a person—as well as the incongruities within a single identity: all of these things can be what they are without justification. An essay that insists on exemplifying and discussing this kind of rest is a form of resistance because our culture too often moves to gloss over the reality of traumatic histories and current crises. What I mean is: allowing truth to rest unaltered is resistance. How would you define this resting place and why was it important for Rancher to create this space?

SS: I love what you have said here about community + writing as sites of rest that do not require us to straighten our stories in a way that renders them consumption-appropriate for the white/cis/straight audience that Empire centers.

In the case of Rancher, community and writing dovetailed in such a way that cast the book into its form.

While writing Rancher, I wrote close friends and asked what a story about rape was supposed to do. I didn’t know! But I felt my not-knowing was meant to happen inside the alchemical basket of friendship. I included some of those responses in the book. In fact, the notion of a story being a place to rest was part of a friend’s response to this query (the brilliant Julia Cohen!). Prior to this book, I thought of healing as a largely privatized event. This writing experience taught me so much about the value of healing as something that happens with/in community.

We are fortunate because right now there are folks doing incredible work on rest, pleasure and resistance work— Tricia Hersey, Adrienne Maree Brown, Karen Walrond, and others. I love what Serena Chopra has to say regarding queer desire and queer narratives resisting legibility in a recent This Plus That podcast episode. These visionaries are all women of color, who rest least of all on this planet.

Tarpaulin Sky: It might sound strange to someone who hasn’t read your book yet but, to me, Rancher is an essay about rape and laughter. Early on you imagine getting together with friends to laugh about your collective obsession with black widow spiders, “…the three of us together, laughing. In this dream, we are safe and have what we need” (11). So here, laughter is associated with safety. This seems like an ideal environment. However, there is a whole section of Rancher that explores why terrorized people laugh. It documents theories about the denial of fear through laughter, laughter representing being broken by cruelty, laughter as an expression of submission, or to help people regulate emotions in extreme situations. You also include an example of being terrorized by your rapist at 14 and echoing him:

When I was [my rapist’s daughter’s age], in the moments before her dad would rape me and/or oversee my rape by others, he called me Orca, as in, his words, a fat ass whale. Everyone thought it was hilarious. I laughed, too. (15)

You don’t identify which category of laughter your own fits into in these moments and the multiplicity of options is haunting. Decades later as an adult, you describe laughing in response to feeling embarrassed for your therapist, “Living, she concluded, is not for the faint of heart. And then she laughed. She laughed so hard I felt embarrassed for her so I joined in. Then I was really laughing. Later that day I thought, for the first time in a long time, maybe there was hope for a person like me” (37). What starts as a response to discomfort becomes a symbol of hope. Laughter holds a different potential now, a potential for healing. When you reflect back on your earliest memories, does laughter always relate to trauma or does it frame your childhood in other ways? What categories of laugher do you relate to the most now (it seems like there is laughter as safety, as healing)?

SS: As you note, laughter can function in multiple ways and humor can be a mode for dealing with the complexity conjured by extraordinary juxtapositions that trauma often generates.

Each person’s laughter has a unique signature, like a fingerprint. Scientists posit that 10% of our laughter’s sound and “shape” is rooted in our DNA and I’m fascinated by that 10%. When laughing, the body opens. Do ancestors speak through these eruptions? Which also puts me in mind of the fine line between weeping and laughing…

If you hear a child ghost laugh it can be terrifying. But if you try and remember your dead father’s laughter, it can be heartbreaking. I appreciate laughter’s ability to hold paradox and contradiction while functioning in simultaneous, multivalent ways. Laughter won’t be pinned down. It can’t be fixed. I couldn’t say what it is (or isn’t).

I do know that when straight male comics court laughter by using queers, trans folx, and #MeToo as a way to carry jokes, often to “prove a point” about comedy in the name of keeping it subversive and therefore powerful, that this is a failure of imagination. Such comedy, and the laughter it seeks, is less a call for comedy to remain powerful through subversion, and more a nostalgic throw-back to a time that was always systemically corrupt. That sort of nostalgia is both boring as fuck and also dangerous because people’s material realities and physical bodies pay the price for a culture that permits dehumanization and dismissal. Cruel laughter is having a very long moment, it seems.

Tarpaulin Sky: Your mention of cruel laughter in this moment could not pierce any deeper, as this interview began when Roe v. Wade protected women, families, and futures, and now that protection has been rolled back with the recent Supreme Court ruling. I’m also thinking about how to find the inner space your therapist referred to as a “healing crisis.” You work with oxymorons like this in Rancher—writing springing from a relationship of opposites. For example, the term “healing space” contains a divot between the two words, and that is where I think action comes from. The connection you make between cruel laughter (not the laughter of saints, of suffering, of having suffered) and resurrection really stands out to me right now considering this space. On pages 41-42, you weave a definition of resurrection that is poignant this morning as I write to you (note: the Joan mentioned below is Joan of Arc, with whom Selah communes throughout Rancher):

“I’ve been writing this essay so long that the fake-ass story of [my rapist’s] death is becoming true. The liar, turns out, was a prophet. Prophets are often depicted as laughing. …

Personally, I feel like I can never stop thinking about resurrection. Resurrection sickness. I get bouts. A pitch-dark sphere pushing out a flower at double bloom, which retracts, and then blooms again. It smells of bitter chocolate mixed with menstrual blood and moss.

‘Listen, if you stick around on the Wheel long enough every lie becomes true,’ Joan says. ‘It is, literally,’ she emphasizes with a dramatic exhale of cig smoke, ‘how the universe works…’

The resurrection of my rapist is also a re-inscription of his demise, the void’s flower face that won’t stop throwing up on the edge of anguish. And this essay is an abandoned church. And I’m in attendance.”

This passage ends with the oxymoron of an empty church in which the speaker is standing (or haunting). And then on page 44, you add: “I wish rape was more like a ghost. That after some process of recognition, it would, at last, disappear.” This is such a powerful wish, for an end instead of a loop or finality instead of the looming nature of trauma’s potential resurrection. Resurrection is what happens to anything interred, no matter how deep, no matter where. The shifts of the vessel containing what has been buried will bring it back eventually, though not always in the shape or living the life as we have previously known it. It’s less like a blessing or a punishment, and more like a guarantee. The loop of resurrection is also the shape of this essay. Can an essay be a resurrection, a burial, a space for action or reinvention, a site that diminishes the grip of resurrection? What place does resurrection have in your writing practice – particularly in essay writing?

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Joan of Arc, by Tom Taylor” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

SS: Thank you for these thoughtful questions. I admire you both so much as feminist thinkers and writers and it has been a pleasure to be in conversation with you both. I don’t identify as a Christian. That said, since I was a child, I’ve been influenced by the Book of John. My mother, my Aunt Penny, and my grandfather Lala, would have extended philosophical discussions about this most gnostic of the canonized gospels and from a young age I loved to listen to these discussions—they were alive with wonder and valued the question as a mode of engagement. We were always a family that celebrated the great ghost stories: in the beginning was the word and the word became flesh and dwelt among us…and of course later, the wordflesh dies, but when we put it in our mouths…we reconstitute it…as a book. The Eucharist: ancient hardcore magic! So I’d say: sure. Essays can be resurrections. They can be any aspect of the resurrection cycle. How many lives in this “one life”? How many essays, how many books, in the writer with her many deaths and births?

I’d also add: resurrection is not for the faint of heart. Take for example the Lazarus story, which is a horror story. Can you imagine—reanimating fleshrot-sagging on the bones, and then moving that flesh about once more? The Old Testament is very Death Metal in its moments. A great take away regarding resurrection is that it reminds us that to choose to keep living is not always easy, but if we are willing to lean into the discomfort of this messy complexity, our capacity for a deeply felt and rich, textured human experience dramatically increases. The goal is to feel. Period. Not to (only) feel better.

Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “Full-page miniature with four scenes: Christ in Limbo; Resurrection; Marys at the Tomb; Noli me tangere, fol. 8.” New York Public Library Digital Collections.

I’m currently finishing a novel that takes place in the world of the dead. No one in that book is resurrecting. But they are singing. Their choral lamentations are transfixing. They contain every ache, every bright streak of rage and desire, regret and hope, every story is there. I listen all night.

Over twenty years ago, I remember it was the day after Christmas, I came close to becoming lost in the Roman catacombs. I wasn’t following the rules. I tend to (mostly) follow the rules actually. But something in me rejected those rules and in an almost, well I’d say ecstatic state, I just decided I wasn’t going to follow the rules (to stay with the group) because I couldn’t get lost in a place where I belonged. I didn’t feel afraid or anxious. It was a remarkable relief. I felt, finally, like myself. Walking in the pitch dark, in silence, through sanctuaries of absence lit by the inverse and what is beyond the inverse—sometimes writing gives me this feeling. Resurrection is extraordinary and a miracle and horrible and amazing and bodily and gross and flowering. But where I feel the most at home is in the between spaces. Tending to the holy darkness.

Tarpaulin Sky: Your work in these between spaces is prolific and significant. Right now, you are doing a ton of projects with Four Queens. I’m thinking of the monthly homilies you’ve been writing this year focused on the Chariot card. A homily is something like a sermon. This is what I see as the seed of another important idea to this book and to the work you’ve done for Four Queens: cycle breaking. Cycle breaking is choosing to be the person to live their life differently in a lineage of others who have not made that choice for their own reasons. It makes me think of Rancher as a work is indebted not just to the people in your lineage who failed to create change, but also to those who desired change or introduced incremental change. Desire is like reinvention.

I see this spiritual work as lending itself so easily to writing in the programs put on by Four Queens. Can you tell us more about Four Queens and how this project relates to your sense of collective work or your desire to engage the community in divinatory writing/practices?

SS: Thank you for this thoughtful reflection of Four Queens. Four Queens is an online platform I co-curate with the remarkable writer, performer, and diviner Kristen E. Nelson. The Four Queens are a reference to the four queens in a deck of playing cards or a Tarot deck. We created Four Queens because we wanted a space that could host different types of conversations regarding where the divinatory and oracular conjuncts with creativity. And, we wanted to teach what we wanted, how we wanted. And we wanted to uplift others in a variety of ways.

I love the incredible conversations that have happened at Four Queens through its classes, events, curations, mentorship opportunities, divination sessions, and exciting programming curated by others working in the expanded field of Creative Writing and Divinatory Poetics.

I love the Four Queens Reading Series and special literary events. I love that this series, often intimate in its gatherings, hosts writers doing exciting, vulnerable, nuanced, complex, risky, and extraordinary work. I love that so many of our visiting writers feel safe enough at Four Queens to experiment through their performance and/or share work that they won’t share elsewhere. Four Queens is that sort of space.

I think it is spot on to say that Four Queens celebrates cycle breaking and the cycle breakers. Four Queens believes femmes and queers when they speak about invisible matters with authority.

The cards—to use Rachel Pollack’s term, the seventy-eight degrees of wisdom—are inherently calibrated towards liberation and dismantling oppression. They invite us to risk having a different sort of relationship with uncertainty. They help cast the conditions through which we might make contact with the wisdom embedded in our own somatic kingdoms. Every card opens into an archive that cannot be exhausted and I want to root around in those archives for the duration of this life. I get very excited (especially excited about femmes and queers) having access to this liberation-based technology.

About the Author

Selah Saterstrom is the author of two works of nonfiction: Rancher and Ideal Suggestions: Essays in Divinatory Poetics, and three novels: Slab, The Meat and Spirit Plan, and The Pink Institution. She is the cofounder of Four Queens, a platform centering Divinatory Poetics, and she teaches and lectures across the United States, and is on creative writing faculty at the University of Denver. She lives with her wife and daughter in Colorado.