Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with

Tameca L Coleman

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. Opening 2023’s line-up, Tameca L Coleman discusses their book an identity polyptych (The Elephants, 2021) the complexities of photograph as memory and committing violence in a text.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Tameca L Coleman

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. Opening 2023’s line-up, Tameca L Coleman discusses their book an identity polyptych (The Elephants, 2021) the complexities of photograph as memory and committing violence in a text.

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. Opening 2023’s line-up, Tameca L Coleman discusses their book an identity polyptych (The Elephants, 2021) the complexities of photograph as memory and committing violence in a text.

an identity polyptych by Tameca L Coleman (The Elephants, 2021)

Excerpt:

My Blackness is a Constant Question

When Curtis Mayfield sings, “High yellow girl, can’t you tell / you’re just the surface of our dark deep well? / If your mind could really see / you’d know your color the same as me.”

When Toni Morrison observes that “Now people choose their identities. Now people choose to be Black. They used to be born Black. That’s not true anymore. You can be Black genetically and choose not to be. You can change your mind or your eyes, change anything. It’s just a mindset.”

Rachel Dolezal. Martina Big. Jessica Krug. Blackfishers on Instagram. Those of us who can pass as white. Those of us who can be racially ambiguous.

In Oakland, walking through a beautiful, old money neighborhood with established trees, I say that I would love to live in a place like that. My friend turns to say, “and what? Forget about our people?”

My classmates get mad at Ourika for not siding more with “her people” and I try not to speak, but I feel everyone waiting for me to say something because they think I will agree. I am the only brown person in class. Ourika hadn’t grown up in the communities in question. Neither had I.

Every time I was told that I wasn’t Black enough to talk about Blackness because I talked like white people and didn’t grow up in the right neighborhoods.

“B-L-A-C-K, N-U-S-S, B-L-A-C-K, N-U-S-S, B-L-A-C-K, N-U-S-S. B-L-A-C-K, Black is okay!”

That time I walked up to the cash register at REI and the cashier looked me up and down and said my mother must be proud because I was so polite and because I talked so well.

No one ever believes there are Black people in Idaho.

***

Tarpaulin Sky: The poems in an identity polyptych string together a picture of continued unease with how the young speaker is treated by family members too consumed with their own needs/perspectives, as well as outsiders scrutinizing the speaker’s racial identity. A mood of discomfort and frustration hangs over this collection as the multiracial speaker is never experienced as enough by others in the early years this work captures.

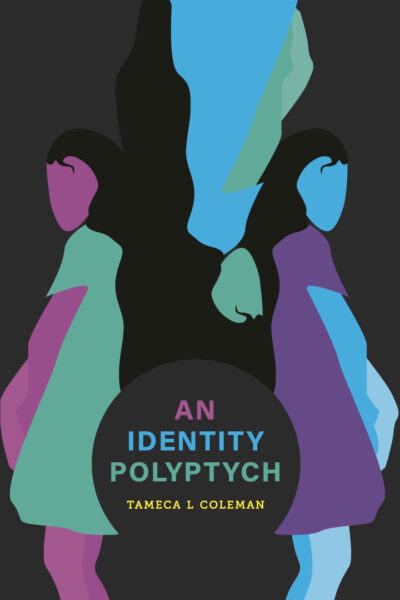

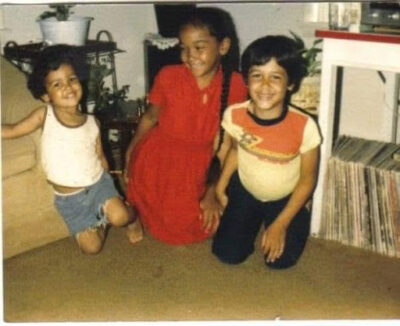

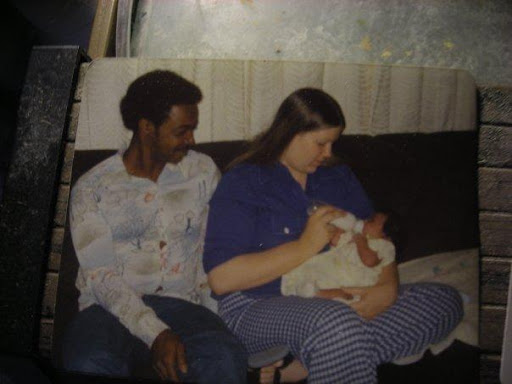

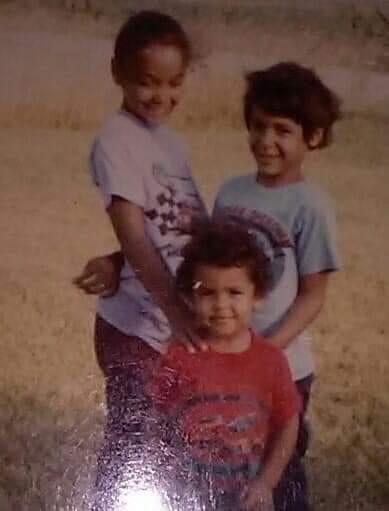

The inclusion of idyllic or upbeat childhood photographs creates a powerful counter-narrative or layer of ambivalence. For instance, one depicts three siblings smiling at each other with the caption, “We look happy here.” The word “look” stings the reader. Is the photo deceptive or does it convey forgotten moments of childhood glee?

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

I’m reminded of an exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art called “Based on a True Story.” The exhibit features many artists whose pieces contain both reality and fiction. One question posed in the exhibit is: Can photographs contain fiction? The exhibit featured James Luna’s installation “Take a Photo With a Real Indian” and the cutout of himself in business casual attire next to him dressed in Native clothing, as well as Matthew Barney’s “Cremaster 2: The Drone’s Cell,” which is a portrait of Barney dressed to portray a serial killer after his second kill, the photo embodying both the artist and the killer character.

James Luna “Take a Picture With a Real Indian” via Garth Greenan Gallery

By using photos in this book, readers are offered an alternate fiction of memories the person capturing the photo wanted to remember. This may be colored differently than the writer’s own. The photographs included in this collection could be seen as an equalizing, a disruptive, a misleading, or nostalgic force. If you do find it to be a force, how would you characterize its impact?

Tameca L Coleman: I really appreciate your comments, and for reading an identity polyptych, and for conducting this interview with me about it.

When you say “beautifully crafted,” I nervous-laugh at myself a bit. I always describe myself as having thrown a lot of stuff at the wall to see what can stick, and to make sense of it. I think the original manuscript, turned in to Khadijah Queen, one of my mentors at Mile High MFA, was darn near 200 pages. I tried a lot of things, and very quickly: list/catalogs, interviews, explications, collection of/defining of terms, attempts to connect with family, with healing (often forcing it), artifacts (i.e., photos), questions for readers, myself, freewriting, poems, prose, theater, dialogue, fiction (which didn’t make the cut because my peer readers said all of my fiction was “lying” (!). I tried explicating my own texts, implementing footnotes, cross sections, back sections, etc. unsuccessfully (although some parts of this work will probably end up being another book or two at some point). I also had a lot of chaff which has been collecting dust for a little while.

Another one of my mentors, Eric Baus, talked a lot about “trusting the catalog.” At the time, I think we were specifically talking about catalog as a poetic form. Coincidentally, catalog is one of my favorite poetry forms to work with because of the way the anchor or fulcrum point is you, and a catalog tells a story by that anchor or fulcrum being what (who!) it is.

I also took to heart a lesson on narrative arc from David Hicks, one of the founders of the Regis MFA program, and I integrated that into my book as an organizational tool and process.

So, this is just to say that I had no idea what I was trying to do or say in the text and, despite whatever memories and feelings and knowledge I had, I didn’t quite have words. I felt pretty isolated in my experience. I had no idea if this work was even important other than the healing, or if it would cause damage if it was ever published, and I experienced a lot of tumultuous emotions because of this.

When I registered for my MFA, I really just wanted to write sweet, cute, funny stories, but the material that would later become an identity polyptych was what was coming out at the time because I desperately wanted to heal, to understand, to feel like I belong somewhere, and to be able to get to know my family. This of course is soul-deep stuff.

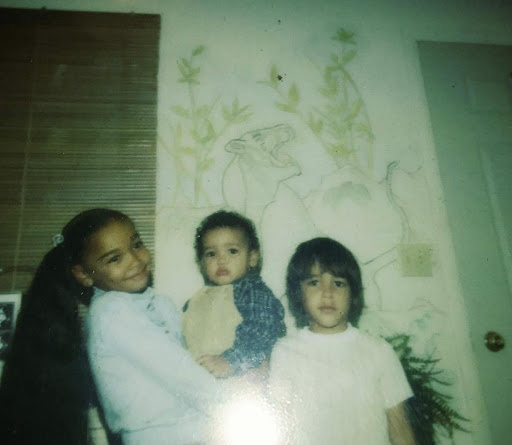

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

I didn’t really write the book for anybody else but, during the course of my MFA, I began experiencing how incredibly helpful it was to read others’ stories (I started feeling less isolated and lonely in that way). I was throwing together all of these pieces that I had written during the course of my MFA to sort of complete the assignment. I maybe never really believed it would be a published book. Some of the pieces in the book are from long before MFA times. All of this work is stuff I would have sat on if people like Eric Baus and Andrea Rexilius hadn’t nudged me to send this work out.

While I was piecing together many bits, arranging and rearranging them, I was also introduced to so many amazing writers who spoke about healing, familial estrangement, grief, being in between things as a mixed-race person, looking for community, and much more. I found myself in a state of unwinding and recalibrating. I was experiencing a lot of what I call belated cognitive dissonances about race-related subjects such as interracial marriage, racial ambiguity, generational trauma, hidden or silent racism, respectability and identity politics, colorism, etc. I am still in a state of constant unwinding and recalibrating (and still writing in ways I call “catch-as-can”). For this reason, I personally consider this book a bookmark that is deserving of many cuttings, which means I need much more time and support if that work is to ever be done.

I appreciate your reading of the text, and your questions. One of my anxieties about this book is that my understanding and movement towards compassion (forgiveness?) wouldn’t come through. This is one of the reasons I state that this book is just a beginning of my textual unwinding.

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

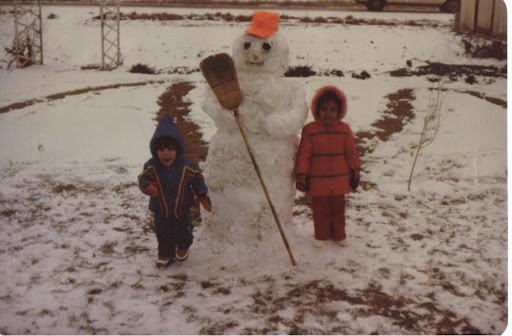

There are times when I play with irony, and I’m not completely sure how to approach the counternarrative idea but let’s try: I have few artifacts from my childhood and what time I was able to have with my father’s side of the family. There is also irony in my understanding of each photo, because often I remember what I was feeling, my perceived context, and that always something was not ever quite right. I’m thinking specifically of a photo I think I meant to put in the book, but that didn’t make it, of my brother Will and I standing in front of a snowman that my grandfather on my mother’s side helped us build. In my mind, my brother and I were at my grandparents’ house for maybe a couple of weekends, and when my mom tells the story, it had been many months. Her and my father were separated at the time; Mom was living somewhere else, trying to figure out another life for us that ultimately didn’t work out. I remember this moment as a happy time. At that time, the weather at my grandparents’ house was a pressure that neither my brother or I could detect. We got the good grandparents parts.

There is another photo of both of my brothers and me in front of a mural that had been drawn in the living room of the house on Pinetown Road. I didn’t find that picture in time for the book, but it was kind of perfect that it was replaced by text instead, because for me, these artifacts aren’t readily available, if they are at all, many of them having been lost in the family rift, and some maybe having been destroyed.

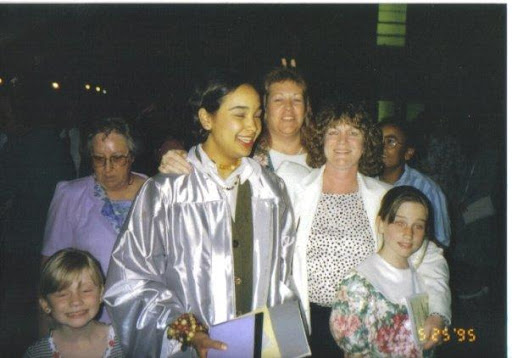

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

I wish I could remember who wrote the essay I read about photographs marking time, how they are bookmarks, and how we pose for these bookmarks. As if the smiles in those photos can replace the actual weather in those moments (and of course sometimes those reflections are more truthful).

But, coming back to the counternarrative idea: I suppose that feeling of counter or disparate can come because, for me, the photos are part of my piecing all of this together, trying to make sense of holding multiple things at once. Like feeling love for everyone in my family and yearning to understand why whatever happened happened. Growing to understand and still feeling the trauma in my body, seeing the traumas in the bodies of my family, and in those who caused damage.

Sometimes the memory of trauma completely obscure’s feelings/memories of joy, happiness, or instances of love being transmitted. I can’t remember at the moment if this made it into the book, but I do ask this question every day: Why don’t I remember this love that I’m seeing in a particular frame? The evidence is there.

I also consider all that is missing. In the past I felt a lot of anger and a tendency to blame. Understanding this now creates yet another cognitive dissonance that takes time to do its healing work because, along with everything else, I have caused damage in pointing fingers and really forcefully asking (demanding) why did this happen? Are you ever going to say you are sorry?

You asked specifically about the photograph with the caption ,”We look happy here.” That was a picture that my mother’s mother snapped when her and my grandfather came to visit. It probably goes without saying that no matter what anybody knows, when the parents are in town, probably everyone is on their best behavior. Those times were hard times on a lot of levels. We were posing, looking like cute children who didn’t have problems with each other for the sake of that bookmark.

[I feel like you’ve just given me a writing prompt in regards to the museum exhibit that you have described, and I am curious about following it through in whatever, setting, alone, or with others, should anyone also want to participate].

If I am explicating this work, myself, I think the images are artifacts of people holding onto what they can, and trying the best they can. If that’s an alternate fiction, and I suppose it is, maybe the photographs are reminders of things like youth, and beauty, and that we were there at all, and that we tried. If I could ever convince my mother to tell whatever she needed to tell, the filter would be different. My memory, unfortunately is filtered through the eyes of who I was when I was that little girl, and also through broken memory and the passing of much time.

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

This reminds me of another anxiety I have about this book – that I can only ever tell my own story through whatever filter I have at any given moment and, through whatever is resolved or unresolved, the other characters in this story don’t necessarily get a chance to say what they need to say. On this point, I feel a bit wrong in publishing this book. It’s not that whatever I conveyed didn’t happen but it’s that I would rather side with love than with blame, shaming or condemnation, and I am never sure if I sided with love enough on account of my own pain.

In these ways, an identity polyptych can be considered fiction, because memory is tricky, and so is that want to side with love. And so are all the emotions tied to those memories. My current understanding of the story is one piece of the whole. And yes, there was abuse and rash decisions made for survival. I know that must be acknowledged. I also know there’s so much more to this conversation and it doesn’t end at all of the things that went wrong.

TS: An untitled poem in this book begins, “You can’t just read your way out of racism” (25). It ends with the lines:

i take notes and carry

the weight of them.

I underline

and highlight. read with yearning.

the more i read, the more i know

i know

nothing (25).

The turn at the end there is poignant, moving from learning from literature to only knowing how little the speaker knows. Yet, this collection integrates quotes by famous writers like Audre Lorde and Toni Morrison that help the reader consider the relationship between vigilance, small gestures, and revolution.

In “My Black” (27), the speaker is called a racial slur at school and tries to retort to her racist bully that “nigger / was a river / in Africa” to relate that accusation to a regal and important body of water. The poem ends with the need for text to clarify whether her comeback holds up, “That night I consulted / the dust caked encyclopedias on our bookshelves. / Niger has one g. Nigger has two.” It is a tender and heartbreaking moment.

Did you have a desire to understand yourself through literature at a young age? Did you experience the phrase, “the more I read, the more i know” before the feeling of “i know nothing” set in?

TLC: There are some conversations I want to have more about certain violences I have committed in this book. First, I’m often asked why I start with “I do not know when reconciliation comes,” and, second, the usage of racial slurs. You mention the untitled poem and I’d like to add “Winter 1976: An Interview with My Mother Donna Lynn Outland.” A good deal of that poem is an outright lift with small edits, my mother’s words, her patternings of speech. What I needed to happen was for the reader to feel, really feel, the violence in those moments. For example, it knocks the air out of the room when I say “nigger” four times in quick succession.

I had a hard time finding words for much of an identity polyptych but this is something I definitely did on purpose. I think there’s an un/spoken rule about how many times we can use words like that in a text depending on who the speaker is and, of course, context. Violence, when it occurs, usually does not prepare us for its arrival. I needed the violence and terror of this moment to be felt by the reader so the word could not just be a passing mention. It had to be the haunting turn. I needed this moment to hit the reader over the head so they could understand the weight of a moment like this. I do not read it often but, when I do, people squirm.

There are times in my writing when I am also self-examining my own prejudice. I am not sure if you mean this by your question but I will take an opportunity to divulge because I feel it is important. “Toothpick 9/11” originally had the term “Good Ole Boy” in it. I cannot remember at what point this was edited out. If I could do it again, I would have fought harder for its inclusion as well as the inclusion of a vignette called “Tamesha” that didn’t make it and will be in another text whenever I take time to complete it. I’ll post “Tamesha” below this response.

It has taken me a long while to kind of process your second question because this is something I am still unpacking, and probably will be unpacking for the rest of my life. I have experienced a lot of my cognitive dissonances about racism, colorism, etc. late. As a youth, and even in my 20s and 30s, I did not usually know racism was occurring when it was subtle and there wasn’t really anyone able to guide me in this. I could feel something was off or wrong, but I thought it was me as a person, not the color of my skin, not some underlying story/ideology/foundations of our country that none of us can at this point escape.

I am a mixed-race Black person whose indigenous lineage has been obscured and who grew up in Boise, Idaho, estranged from their Black family. The poem you are mentioning that begins, “You can’t just read your way out of racism” is meant to be a mirror for readers who experience white privilege and who are well-meaning, but who think that reading and supporting Black businesses is enough.

The poem also is a bit of a prism in which I see myself. I am someone who has resourced numerous texts for this book, for continued growth (there are a grip of them on my coffee table right now), and who feels mixed-race guilt because I have subsisted in white spaces for a very long time – often because those spaces are the only ones who seem to accept me as I am (so long as I can operate in those spaces and continue to buy into the myth of meritocracy). I am constantly being asked to prove my Blackness and worthiness for that matter (Am I Black? Am I “capable” per the rules of white supremacy?). At least, this is what I’ve felt, and it’s impossible because I have no long-standing presence with any community. Any acceptance, unless I’ve proved this seemingly impossible proof, feels conditional. A “You’re okay with us until and if. . . “

How do I move when every movement feels like a betrayal? Am I a culture vulture for wanting to know about my African and Indigenous ancestry? Am I anti-Black for not wanting to cut my white mother out of the equation?

Yes. I have been asking books for everything for a long time.

“Tamesha”

My plumber thinks my name is Tamesha. I feel better now about forgetting his name, though I consider calling him Staven or Froderick. I look up a text from my landlord and see that his name is Bud. Maybe I’ll call him Bood, and I’ll smile unflinchingly as I shake his hand.

I hate that I think, “How typical,” that a man who’s on call 24/7 for plumber gigs should be named Bud. He’s burnt red-brown from the sun, even though it’s winter. I feel like a jerk.

Bud is a friendly man, prone to smalltalk when he’s not talking to himself. I’m working in the next room and start playing James Brown on Spotify to create a barrier between my work and his. I hope he doesn’t get my stupid joke. I’ve started with “Make it Funky.”

Bud intermittently peeks into my office and lets me know the state of the plumbing. The system is built on old 1 ½ inch pipe, and the problem is just below the concrete. “I’ll tell the landlord they probably need to scope it.” He then asks me where I’m from. I simply say, “Boise Idaho,” and I turn back towards my computer screen, feigning work. Tap tap.

The plumber then tries a compliment, guessing my age to be twenty years younger than I am, then ten. He proceeds to tell me about his African friend, about how she always looked so much younger than him even though she was his age.

“Black don’t crack,” he starts to laugh, looking at me to laugh too. I turn again to my computer screen holding my face in place. I force a chuckle and think, while it’s nice to be recognized as a Black person, this phrase is so strange coming from his mouth.

TS: I once read a book called Trauma Stewardship that described three tiers of trauma — primary, secondary, and tertiary. These refer to the ways that one can absorb violence, even if it’s just hearing about it third person. The first poem in this book is all about the transference of pain generationally. The reader becomes aware this is about shared trauma, and also about how violence begets itself if one does not become cognizant of it.

You quote an unattributed source in an identity polyptych:

“When you separate yourself by belief, by nationality, by tradition, it breeds violence. So a man who is seeking to understand violence does not belong to any country” (12).

The poems in this book seek to understand the many different kinds of violence – racism and colorism to name two major sites of exploration. A stanza that encapsulates the necessity of such searching is on page 10 in “Am I Black?”:

“On the bus, a woman looks straight at me, and says: You know you’re Black, right? I tentatively nod. She says: I’m just making sure because sometimes ya’ll don’t know you Black.”

Another stanza from the powerful first piece that begins the book enters this discourse from a different angle:

I thought about how I hate violence,

and I thought about how we’re facing violence all the time,

the perpetrators of the wounds we carry getting off

scott-free with the language of their kids in tow,

beating us over our heads once again

with demands for forgiveness

songs we do not owe. (3)

A tension arises in this collection between “not belong[ing] to any country” and the need to return to specific locations (temporal and physical) to process these forms of violence. In your writing process, how do you balance the position of displacement with the desire or drive to ground these poems in specific geographic or memory-based locations? What do you keep in mind when writing about violence?

TLC: I have intermittently picked up Trauma Stewardship but unfortunately have not read it all the way through. I think the point you make about the three levels of trauma are really important. I am interested in personally pairing this with readings from Resmaa Menakem’s book My Grandmother’s Hands, and also Job’s Body (a text we often read as massage therapists).

Part of the unattributed quote was sifting through piles of paper and archives and losing some information along the way. This was not intentional. Also, this quote is part of a really significant idea to me (it haunts) by Jiddu Krishnamurti (Freedom from the Known, pp. 51-52). I haven’t yet been able to translate all I feel because of this quote into all the words I need. For now, the quote is just plugged into the book. It’s another bookmark of sorts.

Here’s the full quote:

“When you call yourself an Indian or a Muslim or a Christian or a European, or anything else, you are being violent. Do you see why it is violent? Because you are separating yourself from the rest of mankind. When you separate yourself by belief, by nationality, by tradition, it breeds violence. So a man who is seeking to understand violence does not belong to any country, to any religion, to any political party or partial system; he is concerned with the total understanding of mankind.”

My writing process is kind of catch-as-can, and that’s because there has been literal upheaval and significant disconnection from places and people in my life. Unresolved trauma has kind of continued this pattern. I struggle to remember things sometimes. I think part of that is because there are few places and people who can reflect back certain parts of me.

This book is me trying to find the words and make sense of who I am and what I can do with that, and to also make sense of all the things I am holding at once. Like, how do I hold the want and necessity for people who have harmed me, my brothers, my mother, and who have also been harmed by people in their lives, and who were not afforded the tools to be better/have better? How do I take responsibility for my inability to “forgive” in time or enough or at all? How do I reconcile what I learn in therapy with the need to be part of community and whatnot, too?

A lot of what I remember is dreamlike – partially because that energy of movement has not stopped. I have bopped from this study to that one, and the same goes with jobs and activities. It’s like I’m constantly searching through and via my many interests but I don’t know what the center is. Some places are more present in my mind, like the house on Pinetown Road, which I loved. It was probably in large part because I could feel my Mother’s love for that half acre and HUD home. I remember my grandparents’ house pretty well because there were moments of safety. If I go to certain places in Denver, I have strong memories too, but not until I am actually in those places. It also depends on whether the places have changed significantly.

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

I don’t have any hard and fast rules about violence in my work, but I do operate in certain ways. For example, I didn’t become a lawyer because of the kind of person I felt I might become in service of what that work would entail. I didn’t think it was possible for me to maintain the kind of ethical standards I would like to uphold – and this to me felt like violence. I did not have children because of a very old fear (thanks to many ‘80s PSAs) that children who had been abused most likely would repeat the abuse cycle. Because I had a tendency to kind of monster out sonically and emotionally in my teens and twenties when some injustice or unfairness occurred. I worked really hard to tune that gauge flat.

I feel guilty, often, about the first poem in the book – and this is work I sat on for a long time. It was not originally a part of an identity polyptych. It came later after I was really working to establish a relationship with my father and also my family. But there were some things he said which felt like self-righteousness, and I realized that an apology was never going to come.

I guess, honestly, this is me pleading. Help me to understand how I can reconcile this when these traumas are still in my body, in my friends’ bodies, in the bodies of people who are very dear to me, and who I sometimes am unable to be close to because of these violences that we’ve experienced no matter how I feel about them. Help me to understand how I am supposed to have a relationship with you when what you have done and are not taking responsibility for puts me into a double standard where as part of my work I am often assisting people who have experienced significant trauma.

This poem, and this book, feel like first steps for me in a long process of healing I am unsure of whether I can ever reach the end.

I need you to know that I love my father. I need you to know that I love my mother.

My father died shortly after my book came out. I don’t think he ever read it, so maybe he didn’t know what I wrote. He was proud that his daughter wrote a book. But he didn’t read it. So, all that I hoped for in him stepping towards me did not happen, and might not have happened even if he had read it.

I have other relatives who have read the book, and they are proud of me too. But they feel uneasy and aren’t as excited to talk with me. I am not all the way sure if this is all the way true, honestly. My yearning for their sudden closeness mangles, I’m sure, my interpretation of any distance.

My family on my father’s side are church people. The church says we need to forgive (just as my father said). I feel like there is never really a roadmap on how to get to that forgiveness. We’re just supposed to decide, and that decision is apparently meant to do the trick. But my understanding is that this way of thinking is a violence, too, reflective of so much that books and books have been written about from slavery to current day broken communities as a result of that very same history. It’s a shadow of how we used to hold each other. It’s a whisper in an oncoming wind. The resolve and community is fragile if it is there at all, and we’ve forgotten how to go about the healing. I still do not know how to hold all of this and it is difficult for me to just put it into the hands of a distant god.

Image provided by Tameca L Coleman

Trauma, when it happens, does not give us warning. And that is what Trauma is – it’s too much too fast. I don’t ever want to send someone into a trauma response (and I have, and it’s awful). I have also been triggered on multiple occasions in my personal and professional life. It’s not that I want to punish anyone or make a point. I am really trying to temper these horrible things with love and movement towards love, even when it is difficult.

I also want to be a whole and full person. I know that my stories and experiences mean something, and deserve my attention and acknowledgement. I know that harm has been done, that it is still in my physiology (as is generational trauma and memory). I also know I have always wanted Love, to be that and to experience that. I need whatever I do to be moving towards Love.

And that’s what that first poem is. It’s the question, it’s violence, it’s begging, it’s I love you, it’s all the things at once, right up front, no trigger warning, no resolve.