Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Min Kang

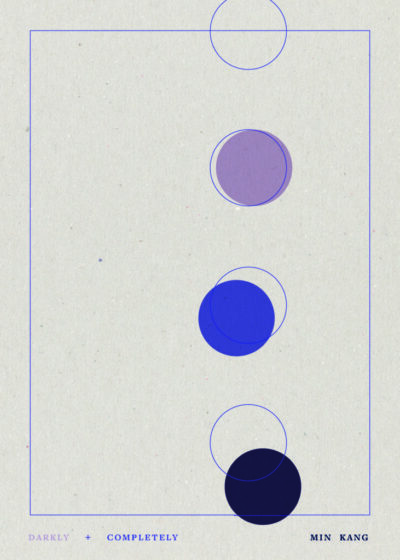

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity, the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Min Kang, author of the Essay Press chapbook darkly + completely.

Julia Cohen’s and Abby Hagler’s Original Obsessions

An Interview with Min Kang

Original Obsessions seeks to discover the origins of writerly curiosity — the gestation and development of these imaginings — focusing on early fixations that burrowed into an author’s psyche and that reappear in their current book. In this installment, Julia Cohen and Abby Hagler interview Min Kang, author of the Essay Press chapbook darkly + completely.

MIN KANG

darkly + completely

Essay Press, 2022.

In 2023, giving birth and motherhood continue to be frequently idealized in Hallmark-like ways. Meanwhile, social media has enabled parenting trends to become more divisive than ever. Parents in Mommy Facebook groups and Reddit threads battle it out over the definition of “natural birth” and debate co-sleeping vs sleep-training or tiger-mom techniques vs gentle-parenting approaches. There is pressure not only to figure out the “right” choices but to show how beautiful and bespoke these decisions look in family portraits posted on Instagram. In this context, Min Kang’s darkly + completely (Essay Press, 2022), winner of the 2021 Essay Press Chapbook Contest, is an incredibly refreshing exploration of early motherhood. In the throes of figuring out what being a mother means and how to keep a little human alive, right or wrong ways to parent are irrelevant. Instead, Kang gives readers the honest moments, such as looking away from the deluge of fluid while a doctor breaks her water in the hospital, hiding gummy bear wrappers from a toddler, and reflecting on the shadowy presence of her own mother. At the intersection of class and race, she shows us the intimacy in questioning who we are once we are at the mercy of taking “orders from invisible desires,” those of a newborn and a mother’s unspoken hopes. Kang exposes both the anxiety and humor in this self-revision process with a variety of poetic approaches like flashes of memory, multiple choice questions, and notes to self (“R U writing bitch”), which wash away any pretense of maternal idealization.

Brief Excerpt from darkly + completely:

I think most people

as mentally well balanced as they may be

daydream about running into their ex in their best formnot in my sweatpants, not grocery shopping, but like on my way to a café on foot and, Oh, my gosh, Josh, how are you—

kind of running into each otherHow fucked up is this, wishing to be 2 weeks more pregnant so that I could tell people, but honestly, what kind of an amazing power move is that

to be pregnant at the time of seeing your ex but withholding that info

God, I’m sophisticated!

*

we were seated at a table with two strangers who used to babysit my bride friend, but they looked only a decade older. my husband blurted out to them that we are pregnant and I was very surprised. he told me later that he was just so happy and wanted to tell everyone we know but couldn’t, so to strangers, it was

*

to say we are low upper middle class is such a mouthful of farts. on the drive return, I asked my husband to drive because I didn’t wear glasses and my eyes aren’t bad enough for contacts, another awkward place to be I can’t recall the music we listened to on the way home nor the discussions we had to pass the time. I guess that’s how that goes—when you wait for something and play it in your head over and over, you remember smallest of details, but when that moment has passed and you don’t even know that it has passed, you recall the waiting part like a good dream or a bad one but a dream nonetheless and you are underwater but still breathing and decide that this is all very terrifying

***

TS: darkly + completely could be described as a text that gestates a child as much as it creates a mother. This collection both embodies very domestic and private aspects of mothering as well as explores the performance of motherhood. Some of the poems examine what it means to accept or reject these positionalities, like staying in a moms-text-thread:

I began a group text with other mothers

to share some NPR article or another

maybe NYTimes?about how our neurobiology is recircuited

into hormonal hot flashes

anxiety riddled car drives

become inconsolable over

piles of laundryand now one of the mom friends is complaining

about her shit husband and

I just don’t know—

should I stay? should I go? (16)

Or relating to characters in a classic:

am prepping to teach The Great Gatsby

hate that I identify with Daisy and Gatsby rich nonsense but flexing on exes. (20)

When we were talking to one another about these poems, we ended up discussing what it was like in early childhood playing pretend mothers with friends and dolls—an early way of performing motherhood as well. We thought that maybe this is when we let mothers into ourselves. Or maybe the mothers in us—whether or not we actually had children—got in another way. When you were young, what did mothering look like to you (your imagined version or observed version)? Where did the mother in you come from and how does she relate to the mother writing this book?

MK: While I was growing up, my family attended a very strict Korean presbyterian church, and at the church’s nursery and play area, they would have these plastic play kitchens complete with pots and pans (something I had never seen before immigrating to America at the age of nine). I was technically too old for such toys because they were so low to the ground and we had to stand on our knees to be level to these play kitchens, but I loved pretending with the other kids whose parents were also at the Sunday afternoon choir practice.

We once got in trouble by a church elder for playing house as a family of a mom, a dad, and their children—the older woman scolded us for being “too grown” and that we were only to play pretend as cousins or siblings only. It sounded so silly to me at the time—what was the point of playing pretend if I’m still me and she’s still her, and now we’re just being us, playing with a fake mini rotisserie chicken between us? I don’t actually recall if we really stopped playing as parents and children, but I do remember thinking that it was odd that this Korean granny thought that pretending to be parents was so taboo.

When we played as parents and children, the “parents” would put on a stern, scolding look while the children cosplaying “children” would beg to play with their friends even though it was a school night. Or we’d hold the newborn dolls in our arms while feeding them with the magical milk bottle that made the milk disappear when you flipped it upside down. (Which reminds me, I have a very sweet video of my then-toddler when she patted her baby doll on the bottom to calm her then lifts up her shirt to nurse her doll. Makes me feel like I sort of did my part in destigmatizing public nursing for future families.)

The mother in me came from my own mother, my proto-mom, my Korean ur-umma. She is my observed version of a mother, and this chapbook was published after her death. In a way, I suppose I wrote this book for people like her when she was a young mom in the late 80s or when I became a new mom—I wanted to normalize the idea that just because you are having a tough time as a mother does not mean that you are a terrible one. Just like every new school I attended or every new job I started, there’s a steep learning curve that can only be overcome by just doing. There was no intellectualizing my way out of the growing pains of becoming a mother or reading my way out of postpartum anxiety.

The mother who wrote the book is one who recently stopped nursing and began to feel like her body was her own again, no more prone to random leaks, mammary gland blockages, or aches. She also was starting to enjoy more free time and tried to recall what the earlier days of motherhood felt like if the memories remained after the sleep-deprived fugue state that she had to function under for the past two years.

My imagined mother was not Korean—she was the PTA mom who participated in bake sales and did not yell at her kid for spilling expensive organic milk after the kid insisted that she pours it herself. She was the advertised, with-it, relaxed mom who solved her problems by buying things to clean or buying time by paying other people to groom her body. My observed mother was none of these things—she cut, dyed, and permed her own hair, and she had no clue what the PTA was or did. She had to redirect her energies to eke out a living with her husband rather than to practice being an emotionally-present mother.

TS: I’m intrigued by your distinction between your observed “Korean ur-umma” and imagined PTA mother. It sounds like your observed mother worked really hard to keep everyone afloat financially and didn’t necessarily have the time to cultivate the emotional resources you pictured in the imagined version. Yet, your chapbook reminds me of the porous quality of motherhood— the way mothers get inside us (after we’ve been inside them).

Early on in the collection, you recount a moment when you unintentionally conjure your own mother, “a facsimile of my mom, who looks a lot like her but speaks English, / appears inside my head to say the following: / You need to be so busy that you wouldn’t know it that you’re sad.” The speaker seems to want to talk with others about “the anger that stems from depression and anxiety” after giving birth but others have boundaries that only filter in the positives.

These poems also bring attention to the challenge of how to create boundaries for oneself as a new mother when you constantly have to take “orders from invisible desires” (4) of infants. Both kids and parents want differentiation and independence but it seems like it must be hard to create healthy distance down the road when boundarilessness is a prerequisite for caretaking a newborn. Pursuing your own invisible desire to have a child, you write, “I want to give myself to my daughter // wholly / darkly / completely,” which is followed by, “I know that that’s not the right answer / it is not the full answer.”

I see so much about boundaries also bound up in the speaker letting go: of coolness; fitting in with both other parents and childless friends; and wrestling with class. You mention how the mother who wrote this collection had recently stopped nursing. Did that separation give you particular insight as you were writing about bodily autonomy/connection? As a parent now, do you see your own mother or her experience with boundaries in a different light?

MK: Your phrase “boundarilessness as a prerequisite” sums up my experience in motherhood especially in the beginning. My younger sister will sometimes text an old photo of me from the first year of my daughter’s life and ask, “omg do you remember this?” and it’ll be a photo of me nursing my daughter in my living room, a shirt half-off but the neck of the tee is around my hairline being used as a headband because I’d get so warm from nursing during the summer. And the fact that my sister saw me in that state and that she nor I didn’t mind it is another example of the state of boundarilessness I had to be in.

My sense of boundaries has definitely changed and is continuing to change as my kid grows older. I remember when I couldn’t use the bathroom without her barging in, but now she understands that her parents want privacy when we’re using the bathroom or showering. I’m also trying to instill a sense of self and confidence in my daughter, so it feels like I’m doing some of this parenting stuff right by her when I witness her assert her selfhood and boundaries with us as well. I hope that I am raising her to speak up for herself when she feels uncomfortable or threatened (in the way that I was not explicitly taught while growing up).

How I view boundaries for myself as a parent has also been affected by the way that my mother did not maintain them for herself. My mother erred on the side of self-sacrifice over self-satisfaction and checking in on herself to see if she felt sustained or whole as a person outside of work and her family. And I’m not talking about the “take a bubble bath” and “girlboss” brand of self-care—I mean, she never ate first so that she could feed others. She never took the time to exercise to strengthen her body and as a way to have alone time so that she could care for her physical and mental health. She had no boundaries or checks-and-balances in place to preserve herself for herself, and I think that served as a non-example for me and I wanted to avoid lighting myself on fire to keep others warm, as the saying goes.

TS: In reading your book, I thought a lot about Mina Loy and her formidable poem “Parturition.” In this seminal poem, she attacks and dismantles the standard narrative of mothers in the late 1800s and early 20th century as subscribing to feminine sacrifice and subservience. She also uses high diction to remind readers that the domestic realm is a space of intellectual prowess. Her poem offers a more grotesque, vulgar, honest view of motherhood than had previously been written by the sentimentalists.

In the midst of becoming and being a mother, the narrator visits the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, reads Alice Notley, preps for teaching at the university level, swaps NPR articles with other mothers, and shares, “while dropping off child at daycare, I had a poem idea.” Unlike Loy, though, your collection radiates an honesty that doesn’t come from grotesquery (or belittling men), but from humor. Humor derived from blatant candidness and self-deprecation. Lines that jump out from this chapbook are:

the peanut gallery that I’ve cultivated in my head says:

keep doing what you’re doing, but I’m bored by how hetero

your poems are

boohoo, your husband

boohoo, aiming for middle-class life

boohoo, your unkempt, torn pussy (19)

when I think of dying alone, I’d rather

die first, one selfish thought I have

besides tinkering at your potato chips (2)

stupid feet

awake at 5am, sauntering about in search of a hot mug (3)

we could say that my life is reduced to

hiding gummy snack wrappers from a toddler (3)

The self-awareness winks at the reader and invites us into the messiness of the mind and the domestic realm. It reminds us that we’re constantly reassessing who we are throughout our life and not just figuring it out when we’re young. At times, who we are can be summed up momentarily as a selfishness toward someone else’s potato chips. How important was it for you to capture humor in this collection? Were there particular people in your life (friends or family), comedians, or other influential writers who shaped your sense of humor that stems from candidness?

MK: Thank you for that thoughtful exploration about the role of humor in my work. To be considered funny feels like a lot of pressure and while I don’t think I wrote this text to make people laugh, I definitely like to laugh (at myself, too?).

It’s impossible to talk about being an Asian mother in America without mentioning Ali Wong—her first special that she filmed while pregnant, Baby Cobra, is one of the first candid accounts of pregnancy that I experienced in mass media besides the sitcom-worthy screams of laboring moms. I appreciated hearing the straight truth from a comedian who is close to me in both age and culture—she educated me and other millennials through humor about the horrors of how you’re not done giving birth after the baby comes out, how you have to pass the placenta next. (Wong did not warn me about how my labor nurse would use the People’s Elbow on my still-bloated belly to squish out the placenta and extra blood. Or, maybe she did, but the lack of sleep during newborn months wiped all that away from my hard drive.)

I’m captivated and drawn to those who are self-aware and also are oftentimes self-deprecating and funny. It’s very human to say one thing but do another, but being aware of this human trait and teasing oneself for it is what I’m drawn to in both people and in creative works. Ginger Ko, a Houston-based poet (who I consider a mom-friend as well as a friend in poetry), comes to mind when I think of someone who is honest and unfailingly funny when she describes her life in her wry, discerning tone in conversation.

Something small you mentioned but is an important concept and truth that I hold dear to my heart (and it feels huge that you have “seen” this belief in my work): “we’re constantly reassessing who we are throughout our life.” When we’re younger, change is more obvious, easier to observe—I hated hearing “Wow, you’ve gotten so tall!” from my parents’ friends while growing up. No, duh, I grew up—I was supposed to. Now that I’m older, I’m not growing taller but still aging in general, and as a culture, I don’t think we attribute inner growth to adults the way we associate inner growth in the lives of children or teens. And it’s not that I think we should always be “improving” or “progressing,” but it’s important to me that I note changes within myself without the moral judgment of “better” or “worse” as tempting as it is to check my growth against my own preconceived notions of where I think I should be or where my peers are. I try to check in with myself about who I am or who I’d like to be to examine where those beliefs are coming from and if I am at peace with who I am or am becoming.

This is all very ideal and how I’d prefer to live and examine my life, but honestly, I’m always one missed meal away (or a befuddling, cruel email away) from losing my shit.

TS: Candidness like you describe can give way to humor defined as the ability to tease ourselves through self-awareness. I think there are moments in these poems where candidness also uncovers anxiety and anger. As a reader, the anger that shows up feels justified even in the context of anxiety. In the writing, it is examined as part of the process of change and it also propels necessary questioning of our everyday relationship to capitalism. One such moment is in the poem “SOME FACTS ABOUT GUILT THAT WON’T MAKE YOU FEEL BETTER” in the beginning:

there’s a lot of “I’d like to” on my mind lately,

to write a ridiculous list of writing methods and call it poetics:

-delete Instagram forever

-unravel in Jamaica, thanks to Southwest’s incessant marketing

-ask an important series of questions when I fail to be productive:am I a poet

R U writing bitch

who profits from this feeling (18)

The last bullet point brings attention to the pressure the narrator feels to be “productive” and the tone turns (humorously) to self-berating with “R U writing bitch.” The question-statement, “who profits from this feeling” juxtaposed with the self-observation offers a stunning question about poetry, yes, as well as a larger question about who profits from the pressure we put on ourselves to project productivity, happiness, or stability. The narrator’s anger, which is always under social scrutiny when mothers display it, drives her to explore the idea of self-acceptance and change as a way to combat profitability. To you, what is the function of anger in poetry?

MK: As I explain what the function of anger in poetry is to me, I feel compelled to explore what anger means to me, period. As you’ve said, mothers (or women in general, I should add) are scrutinized in our culture for being angry. It is a natural, legitimate response, this emotion… and I feel it often when my expectations don’t meet reality or when I realize that something is unfair and not right.When I think about the cultural aversion to women and their anger, I have a feeling that this dislike towards women’s and mothers’ angers have to do with the fact that our anger necessitates change in society. It’s almost as if in the absence of anger, if we pretend that if we are not mad or we don’t demand change, everything must be okay…?

But I also don’t think it’s helpful to assume that all anger (in general or in poetry) must necessitate or facilitate change or progress. Sometimes, you’re mad because everything is the pits,and acknowledging the state of the world and not trying to dig yourself out is the only option at the time. You have to pace yourself when you’re angry, because I don’t think I’ll ever run out of things to be angry about in the world.

Anger has so much range, too, that I sometimes forget to consider the possibilities and the volume of anger. Am I frustrated? What am I frustrated about: something small but because I’ve experienced multiple frustrations all day, have they grown into something bigger? Am I frustrated about systemic oppression that wears me down to numbness and feelings of insignificance? Or is it actually rage?