In the beginning, there is no way to assess, or even to imagine, the danger. Suicide, like many flirtations, starts with something small.

Smoking a cigarette.

Leaving something electric too close to the tub.

Knowing your seatbelt is unbuckled and leaving it that way.

And because modern life provides each of us with the sneaking suspicion that our existence is one of Sisyphus on speed, there is a freedom these small acts of defiance afford us, pressures they relieve, these subtle ways of leaning into and then whispering to death, you don’t have the nerve.

The truth is, it is a shorter distance than you think from recklessness to despair. And because death, as a solution, is so all encompassing, so finite, other ways of coping pale in comparison. In no time, your neural pathways form a perfect arrow leading to the afterlife.

You wake up one morning, and you’re not daring death anymore. In fact, death is daring you. Pointing out, for instance, how when the sun is right, the Golden Gate Bridge makes a black X upon the water. Marking the spot.

Then the research begins.

You find the most famous suicide letters and begin, inside of them, to make a place for yourself.

***

When all usefulness is over, when one is assured of an unavoidable and imminent death, it is the simplest of human rights to choose a quick and easy death in place of a slow and horrible one.

— Charlotte Perkins Gilman

***

The black X upon the bay is by now haunting you. It is home. You dream of the water, bean-green over blue 1. And each night your body jerks awake as it mimics the motion of falling.

The choicest place from which to jump is light pole sixty-nine, facing the bay.

The time from the bridge to the water is four to seven seconds, depending upon the body’s mass and the rate of acceleration.

The body falls at seventy-five miles per hour and kills ninety-eight percent of people on impact.

And this is why, for those of us who wish to go gently, the Bridge is such a meaningful place.

There will be, at most, a bit of blood in the water. No one needs to cut you down, looking into your blue face framed by the rope that hung you, nor does anyone need to scrub away the sunburst pattern your brain might make upon a wall.

Situated between the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge in China and the Aokigahara Forest in Japan, the Golden Gate Bridge is the second most popular place in the world to suicide. And once you’re numb to everything but the possibility of jumping, you can find a strange if unexpected beauty in that.

***

Goodbye, my friend, goodbye

My love, you are in my heart.

It was preordained we should part

And be reunited by and by.

Goodbye: no handshake to endure.

Let’s have no sadness — furrowed brow.

There’s nothing new in dying now

Though living is no newer.

— Sergei Esenin

***

The way in which thoughts of death entered me was through the Trojan horse of manic-depression, which presented itself when I was thirteen. I did not suspect, at that graceless age, that my demons and what I did with them differed so much from anyone else’s.

Mental illness, in my case, began with cutting. This wasn’t something I learned to do. It was something that rose up out of me, as though just beneath the skin a crucial text was making its way to the surface and in order to read it, I had to trace it from the outside. Avid reader that I was, the scars soon zebra-ed across my body. Sometimes I cut a word: help. Sometimes a star, which amassed over time into a perfect Milky Way where my thighs met. Sometimes I carved a person’s name, not to show them, never to show them, but because I needed to balance the weight of my love corporeally, to harvest and name the names of my heart. Or, in the case of people I hated, to draw names to the surface like a thin splinter. I believed at the time that blood was the language of God, the surest way to catch his ear. These were the things I was thinking and feeling as an eighth grader. And when in the school year it was time for short sleeves, I discovered just how different, how deviant, I was. My carved arms became a juicy little story disseminated by everyone in school. It would be the first time I was seen as a freak, and the penalty for that distinction all but killed me. To this day I have not learned to embrace my scars. Though at the time of this essay I have not cut in two years, I wear with shame my own scarred evidence. When asked about any particular maculation, I do not answer. I do not give ammunition. I will myself into a mental state in which I become silence itself.

***

When I am dead, and over me bright April

Shakes out her rain drenched hair,

Tho you should lean above me broken hearted,

I shall not care.

For I shall have peace.

As leafy trees are peaceful

When rain bends down the bough.

And I shall be more silent and cold hearted

Than you are now.

— Sarah Teasdale

***

Because the mind is so labyrinthine and psychology so uncertain, it makes sense to talk instead about the body as an instrument of manic-depression.

The way I presented—cutting, burning, swallowing glass—these were considered acts of self-injury, when in fact, I was trying to save myself by driving out the poltergeist who suddenly lived inside and spoke to me at night of unspeakable things. It is confusing the first time your body becomes an instrument of psychosis. There is no precedent for questioning or rejecting your senses. You hear a voice and have no way of knowing it’s coming from inside the house.

Then there is the case of the body as an instrument of mania. I awoke one night from a dead sleep and a too-bright light was humming inside me. I did not sleep for the next fourteen nights. Money moved easily through my fingers. I stole things for the pleasure of doing it. I allowed anyone inside who wanted me, and I lived through them, the etymology of ecstasy from the Latin ekstasis, “standing outside oneself.” But every mouth that moved over me made a fissure, and I started cracking from the outside, bleeding light. And suddenly the world was slow and ink-black, and I realized the way I was sharing my body was not beautiful, but rather an invitation addressed to the brutal and the opportunistic. From that moment on, I lived in my body like a frightened child tormented by dark and darkness both. This was the body as an instrument of depression.

And so the body becomes a pale coin, depressed or manic, depending upon how the mind lays claim.

If human life is an oath, then suicide for me was like an oath recited backwards, a protest against the physical body that gave entrance to that first strange and violent ghost and all that followed. I would use my body as a vehicle for annihilation, and I kept those plans secret, teeth clenched, mouth like the silencer on a gun.

***

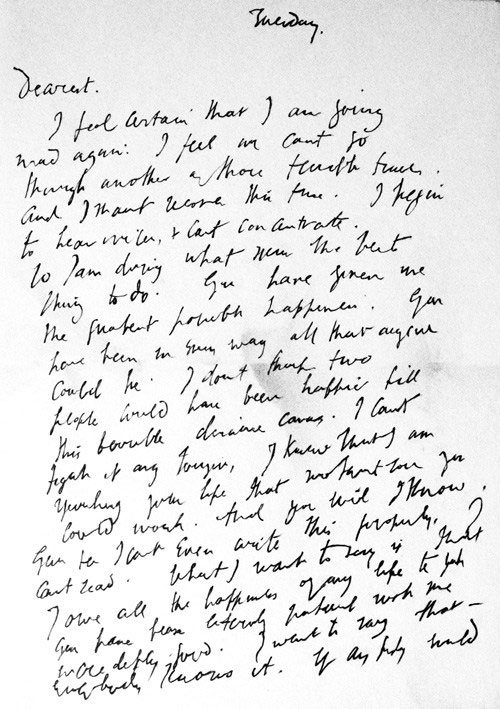

To Leonard Woolf

Tuesday (18 March 1941)

Dearest

I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that – everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.

V.

***

The time it almost worked, the pills I used to overdose were prescribed on February 24, 2005, filled at CVS Pharmacy, and hoarded till spring. There were forty-two tablets of Seroquel, thirty Lamictal, sixty Geoden, ninety Effexor, and ninety Topamax. Three-hundred-and-twelve pills in all.

I stood before the bathroom mirror in my parents’ home, cupping water in the palm of my right hand to swallow the pills in my left. My mouth was as dry as a bone wind, and the capsules kept sticking to my tongue. I expected to feel something powerful, relief perhaps, fear, or even regret, but there was only the urgency of the poltergeist inside. From somewhere far away, my old self was speaking. “You are killing yourself,” she warned. “You are killing yourself.”

Just then, my mother knocked on the bathroom door.

“What are you doing in there?” she demanded. “You’re not trying to kill yourself are you?”

This was not my first attempt.

I heard myself answer, simply, “no.”

I hid all the vials in the back of a bathroom drawer and lay down on the living room sofa. My parents continued to watch television. My sister continued to ignore me from behind her closed bedroom door. I wrote a brief letter, which my mother would later remark was of poor quality for a writer, and then they switched off the lights, locked the doors, and everyone went to sleep.

***

The act of taking my own life is not something I am doing without a lot of thought. I don’t believe that people should take their own lives without deep and thoughtful reflection over a considerable period of time. I do believe strongly, however, that the right to do so is one of the most fundamental rights that anyone in a free society should have. For me much of the world makes no sense, but my feelings about what I am doing ring loud and clear to an inner ear and a place where there is no self, only calm.

Love always, Wendy

— Wendy O Williams

***

I coded that night. Coded again. Died and was resurrected, but only because my mother discovered me. I spent three weeks on life support, woke up, and walked around for an entire week I have no memory of. This is referred to as an amnesiac event. The first thing I remember is standing in the harsh light of an inpatient mental facility wearing bloody pajama pants. There’s a payphone in my hand. Get me out of here, I’m saying, but to whom?

They gave me lithium, three times a day, the pale yellow orb of it. On my tongue, the sacrament of it. All my eyelashes fell out. I told myself they were an offering. That they were black boughs placed upon the graves of everything that ever haunted me.

It was two years before I could focus long enough to read and write again.

“The past,” writes Claudia Rankine, “is a life sentence, a blunt instrument aimed at tomorrow.”

But only if you let it, I told myself. Only if you let it.

***

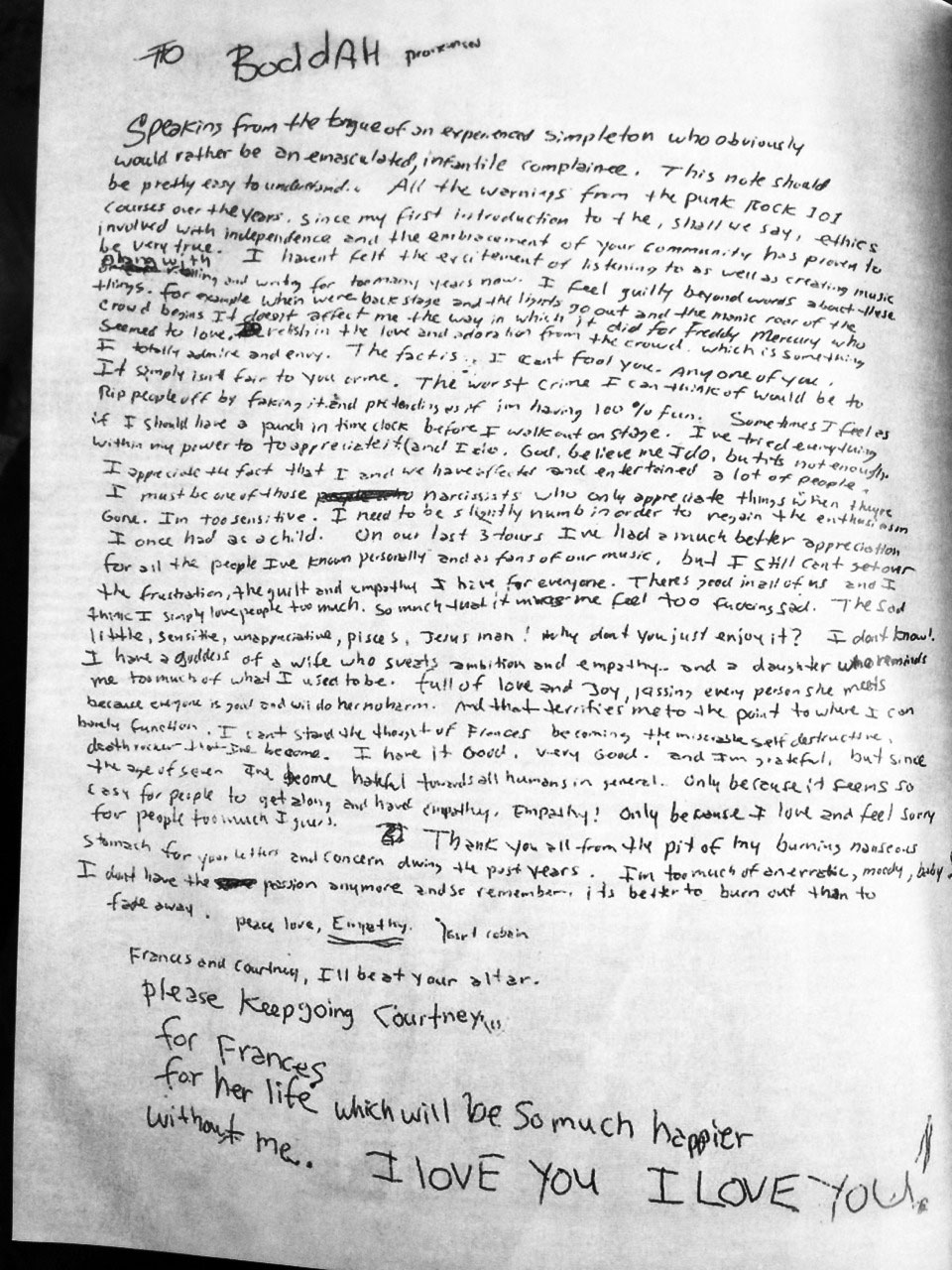

Thank you all from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach for your letters and concern during the past years. I’m too much of an erratic, moody baby! I don’t have the passion anymore, and so remember, it’s better to burn out than to fade away.

Peace, love, empathy.

Kurt Cobain

Frances and Courtney, I’ll be at your altar.

Please keep going Courtney, for Frances.

For her life, which will be so much happier without me.

I LOVE YOU, I LOVE YOU!

***

I’ve said that suicide is caused by a poltergeist that lives inside. But that is truer of my life before lithium. Suicide comes to me now as something external—as, from Homer’s Odyssey, a Siren song—and each day, I do my best to battle the Sirens as Odysseus did, ears plugged with beeswax, body strapped to the mast. For I know the Sirens, oh the Sirens, they sing so slow and sweet.

It has been said of the Sirens that if we could only find a way to sail past their sweet music, they would fall lifeless into the sea. Having succumbed and been saved several times, I know better. Beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, where the bay shines bean-green over blue, a Siren will always lay in wait for me. It’s been so long since I heard one singing, but I am no less afraid. In The Silence of the Sirens, Kafka writes:

Now the Sirens have a still more fatal weapon than their song, namely their silence. And though admittedly such a thing never happened, it is still conceivable that someone might possibly have escaped from their singing; but from their silence certainly never.

***

No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun — for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won’t hurt.

— Hunter S. Thompson

***

To re-enter the world of the living, to redirect neural pathways, or even make a plan that extends beyond dying next Tuesday, this, ironically, has become my life’s work. For the better part of a decade, suicide was my only plan. And though I cannot say this with certainty, I believe I have moved beyond that now.

The question, of course, is how. How did I move beyond it? And the answer, I fear, is so intricate, so deeply nuanced, that I can never know it for certain.

What I do know: I wanted to write a book. And I convinced myself I couldn’t die until that book was published. For three years, that plan was enough to keep me alive, though just barely. And then one day there was love, a love that had nothing to do with me, a love based solely upon the beauty I saw in someone else. Slowly, searchingly, I became accountable to that person, to that love. Wound by wound, I was healing because it is as Rumi says: The wound is the place where the light enters you.

To be clear, no one can kill or save a suicidal person. But for those to whom the Sirens call and call, it is crucial to take what you can get when you can get it. Even the tiniest things can sustain you, keep you alive for one more moment, and those moments will come to something—days, weeks, even years. And one day you’ll realize that no matter how good your reason is for wanting to die, there might be another way out. That instead of trying to solve the overwhelming conditions and crises that led to your suicidality, you can deal instead with the moment, with your impulses, your ineffective coping mechanisms and self-perpetuated myths, and slowly, very slowly, those crises will come crumbling down.

There was this moment after my nearly successful suicide attempt when I looked from my hospital window to the rushed and ragged streets below and saw, beyond the squalor, a fierce, utopian beauty that reminded me of Campanella’s City Of the Sun. As I watched people board buses, cop drugs, and stamp out cigarettes, this singular sentence rose to the surface: please, just give me one more chance to be in it.

It was only a sentence. It was only a moment—I went back immediately to wishing I was dead, but now I had a tool, I had something to work with, and that thing, however fleeting, was possibility.

No matter who you are or what you’ve done, there is beauty inside of you. Perhaps it is only a sliver, but within that sliver, your energy, creativity, kindness, and resilience are stored. You are free to go on hating the other parts of yourself. It is as you wish. But I am here to tell you that no matter what happens, no matter how muted or inaccessible that beauty feels, you have to hold onto it, and believe in it with the fervor of someone who is born again. If you can do that, even for one moment each day, that beauty will begin to sustain you. You will grow into it, and in doing so become more whole than you ever imagined.

Because the truth is, recovery, like suicide, starts with something small.

And someday the darkness that nearly defeated you will serve as a counterpoint, a mode of gratitude, for all of the light you’ve built inside of you.

“Treachery is beautiful,” wrote Jean Genet, “if it makes us sing.”

This is a call to the damaged, the suicidal, and the mentally ill who feel as though they are drowning in darkness. I see you. I see your beauty. Hold fast to it. You are convinced, at this point, that you are all alone. I thought that too. But somewhere in the night, in every city, in every country, all around the world, there is a choir filled with people like you and me, and somehow, against all odds, we are singing.

______________________

1 from Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”

Piper J. Daniels is a Midwestern native who holds a BA from Columbia College Chicago and an MFA from the University of Washington. She is a frequent contributor to the Monarch Review, where she curates an anti-street harassment column. She lives in Seattle and in Phoenix with her dog, Omar Little. Her debut collection of essays, Ladies Lazarus, is published by Tarpaulin Sky Press.

Piper J. Daniels is a Midwestern native who holds a BA from Columbia College Chicago and an MFA from the University of Washington. She is a frequent contributor to the Monarch Review, where she curates an anti-street harassment column. She lives in Seattle and in Phoenix with her dog, Omar Little. Her debut collection of essays, Ladies Lazarus, is published by Tarpaulin Sky Press.