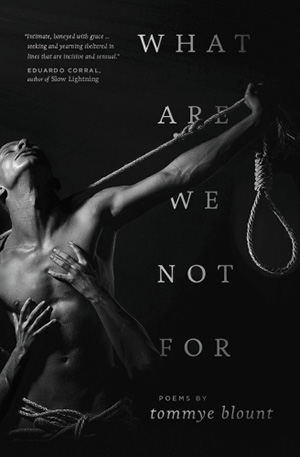

What Are We Not For by Tommye Blount

“Our bodies are museums,” writes Blount, and this stunning chapbook is a museum of the body—as muscle, as sculpture, as urge, as the site of atrocity. The body—entangled with race, gender, and sexuality—is seen as something inexplicable, at times baleful and at times abuzz. Although a thing apart (“By ‘it’ I’m speaking of my body too”), it is a thing with which the speaker strives in these deft poems to come to terms. Through a series of exchanges with dogs, dolls, guns, and lovers, the human form is bitten, pierced, lynched, caught in sunlight, and ultimately embraced.

The Tribute Horse by Brandon Som

I admire the sonic density in this debut collection, wavering with alliterations (“vow vesseling vowel”) and verbal echoes (“one-note hum one’s home makes”). Som writes, “Volume is a word we use to measure both sound & water,” and, as in Niedecker, language and water take on a strange semblance in seascapes that churn with liquid consonants and windy aspirates. The sequence “Coaching Papers,” chronicling the trans-Pacific migration of Som’s grandfather and his rehearsal of a false name adopted for entry into the United States, explores the role language plays in immigration, and shows how a name itself can become an antagonist—and an expedition.

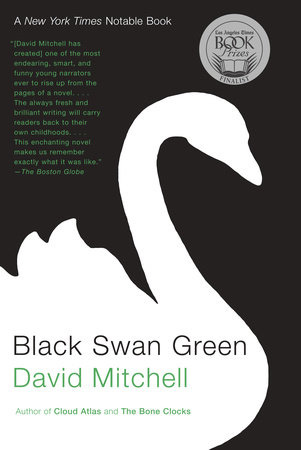

Black Swan Green by David Mitchell

As a person who stutters, I was drawn to this novel, the coming-of-age story of Jason Taylor, a boy who stutters. Mitchell does a wonderful job at capturing the covert behaviors that often plague people who stutter: replacing words (saying “realize” instead of the difficult-to-pronounce “know”), avoiding situations (such as reading aloud in class), and dreaming up careers (monk or lighthouse keeper) that don’t involve speaking. Jason refers to his stammer as Hangman, a name that I think captures the asphyxiating feeling of stuttering, and shows how a person who stutters can feel (as in Blount’s work) at odds with his or her own body. The novel is unique not only for the silences of stuttering, but for its teenage voice, pulsating with cultural references, colloquial language, and a subtle lyricism (“roses brewed the air”).

Illness as Metaphor by Susan Sontag

Sontag takes a Barthesian approach, examining and peeling away the cultural myths and metaphors surrounding illness, contrasting society’s negative portrayals of cancer with its more romanticized view the tuberculosis. Tuberculosis, a disease of the lungs, is spiritualized, the disease of emotional poets like Keats, while cancer, the gradual depletion of the hefty body, is associated with the repression and dispassion. Sontag makes a strong point (which she extends in her later essay on AIDS): when the cause of an illness, such as cancer, is unknown, the patient is often blamed. Fastidiously researched, this book is powerful and revolutionary for describing the stigma associated with disease, and empowers those suffering from illness by naming an often-overlooked part of their struggle. I appreciate the way she views illness as, in part, a cultural construct.

Blert by Jordan Scott

Scott, a person who stutters, notes, “Blert is written to be as difficult as possible for me to read.” The book consists of galloping lists of words, dense with consonance and syntactic compression: “Phlegm scrum knuckles hum; consonant gobstop corpse in clot.” It’s a stunning volume, which, owing much to language poetry, captures the frissons of words, and forces non-stutters to stumble along as they confront the poem’s collisions. I like how Scott, like Mitchell, writes a book about stuttering that does not depict any actual stuttering. While Mitchell focuses on the psychology of stuttering, Scott’s dense sequences explore the stuttering of language itself. I love the title, a neologism that captures the explosiveness of stuttering, and also casts stuttering in a wondrous light, insisting on self-definition.