THE STRAIGHT STORY

Julia Madsen explores her family’s legacy and the intersection of true crime, intergenerational trauma, and the Midwestern Gothic.

The Straight Story

Julia Madsen explores her family’s legacy and the intersection of true crime, intergenerational trauma, and the Midwestern Gothic.

I began writing on degradation and history wearing away. I began writing on longing and felt the corners of the house cave in. The house resembling an archive, from memory, on fire, like longing is fire under the skin, and so I recorded my thoughts before I had a chance to think them. I wrote this over and over and nothing took hold. There was a hole the words drained into, a stream slowed to a trickle, there were sticks and rocks and bits of glass resembling a periphery. In the middle of a clearing I found a passage that could be read forwards and back, the trembling borders of here and there becoming a beyond.

II.

The more times an image is copied, the more its quality degrades. The term for this is generation loss. For instance, if I copy a photograph over and over do my hands begin to erode, do my eyes look away, how far will one go to lift the eidolon from photographic paper and does the same hold true for memory. Do the words themselves decay, these are a few questions I have. Retracing the ancestral landscape, I came upon a family album half-erased by rain and wind whose pages became filled with names for doubt. I wrote my name on a place marker, I wrote my name on a grave, I wrote my name over and over.

III.

Last night I dreamed that I was in an episode of Cold Case Files. I was lying in the center of a field that could be anywhere, I was lying in a field of irises and let the violet light wash over me, I was covered in flies, a disembodied voice said there is time / there will be time, there was pollen in the air, the feeling of being left out all night.

IV.

The art of the true crime documentary is narrative suspense, of perceiving and feeling the ratcheting up, the turn of the screw. A way of unveiling and coming together, edges meeting, scraping away. Reader, I tried to write a real-life murder but could not muster a narrative that might sustain it. I collected newspaper clippings. I obtained court documents and testimonies. I interviewed my grandfather, though I lost the recording deep in a library, I lost my camera too, I lost my keys, but I think I can remember what he said or at least the feeling of it. I intended to approach a history nestled somewhere among the unending rows of corn, at once a maze and straight story, a narrative unfolding from beginning to end with acres and acres between.

V.

The art of the true crime documentary leaves us askew for some time before the spell fades, before the sublime falters, before we forget. The body withholds the shadow of a memory, remembering the pinprick in the finger, the splinter working its way back up. Why time is like an artifact hurtled in our direction or is it a curtain between present and past. I digress because it is a way forward and the only path (topos, topographic) through.

VI.

Early in the morning she picked up the shotgun. Eternity is a small clearing in the middle of a field. Flies buzzing in the corners of the room. She flew out of the house wearing a blue polka dotted dress. She threw the shotgun in the water tank and placed the two kids in the car and started driving.

VII.

On September 14, 1942, the court documents state, Henry Madsen was blown into eternity. There are many other facts that pertain to this case, but when I reach out for them they become grains of sand and like this I am only able to relay what I have heard and read, what I have known but cannot yet put together. A moment rises and is blown out like smoke through the window. How there is no way of knowing but to imagine why, or how the event came to occur, what horizon. A sequence of flies lifts up, they carry themselves across the threshold, the threshold grows wide, eats the flies whole and swallows them into its dark cavernous mouth where I have seen the days pass and there is only absence left.

VIII.

What could bring this into. Or maybe a barren field. The letters of the alphabet pile up like dead flies and time sweeps them away, time sweeps them all away. The candle wax collects. A glass trembles and the flames waver and we try to remember desire like a seed in its shell, waiting to be cracked. I walk along and turn back. The passage no longer leading to the point.

IX.

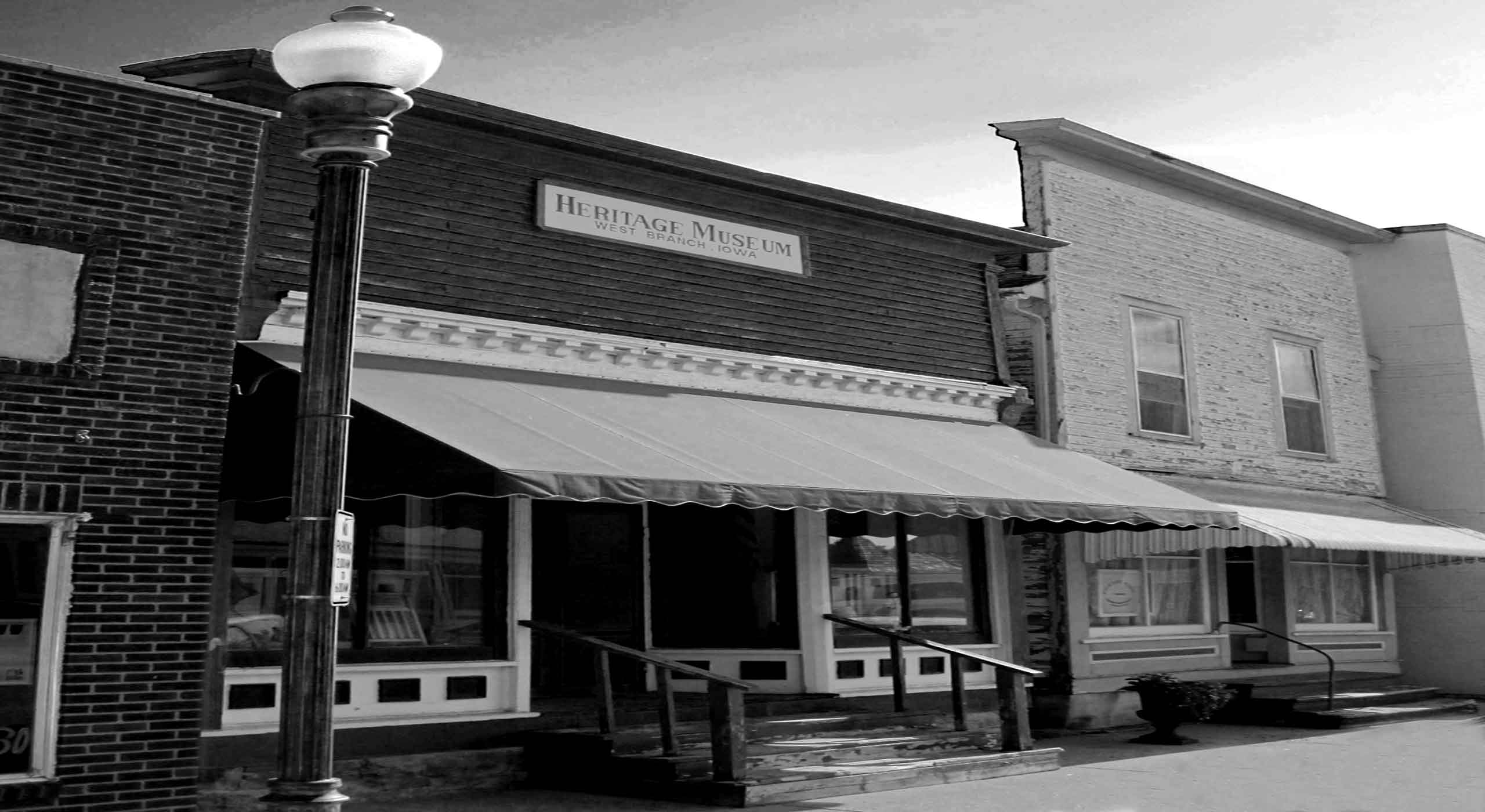

West Branch, Iowa lies on the west branch of the Wapsinonoc Creek whose waters trickle through marshy wetlands. That Herbert Hoover grew up here and has a museum is the town’s most notable attraction. As a child my family attended service every Sunday at the Lutheran church, though I feel so removed from that time that it has become yet another site of the past which remains a mystery even to myself. I tread indistinct apertures as if leading back to a room. There was a shelter hollowed by wind, furtive and unknowing, a place where secrets go on for miles into the vanishing point. Down the road, my great-grandparents’ farmhouse still stands in the middle of a cornfield almost hidden from sight.

X.

Most vivid is the sound of the church bell in the tower which, when pulled, lets out a deep intonation echoing over the fields. Henry and his family helped raise the structure. Built in the Carpenter Gothic (aka Rural Gothic) style, the church’s frame resembles that of the small, modest farmhouse made famous in the Grant Wood painting. Their distinctive upper windows become an enduring focal point, drawing the eye toward a kind of harsh verticality in stark juxtaposition with the landscape. I imagine that we are in such a window now, looking out on a scene.

XI.

In the morning I meet with a friend over breakfast and tell her that I am struggling to begin writing this essay, a kind of true crime meets—what—I am not sure—but maybe the unknowing leaves room for visitation, a poetics of encounter, at the least, at most, revelation.

XII.

This is about failure and the time it takes—

XIII.

Every day begins in waves—

XIV.

Light leaks—

XV.

I write, of the sequence of events, I put down—

XVI.

They slid into the ditch, for the rains had come. She told the kids go run. They ran through the bean fields. My grandfather would tell you. How the officers had found them, crouched in the middle of a field.

XVII.

She rode the length of what afternoon and kept running for days. Slept from hayloft to hayloft. Then they sent the hounds. They had men on foot and in the air. They followed the current and searched the riverbed, they thought she drowned herself.

XVIII.

She says, I do not recall anything either about the death of my husband or my escape or hiding out or about writing to my mother while I was hiding out or about telling her how she might establish contact with me or where I left the boys.

XIX.

Her mother says, I never saw Henry strike Ruth but once and that was after

Her mother says, They had just got moved in in January, it was a new home on a farm which he

Her mother says, She didn’t remember and couldn’t tell me

XX.

Though I have heard stories about the murder since I was a child, it is impossible to determine or decipher their veracity. I imagine that all of them are true in some light, if truthfulness here relies not on facts but on a kind of emotionality that arises from being in a particular time and place. One story goes: their neighbor, on his deathbed, confessed to seeing Ruth’s cousin crossing the bridge right after the murder. Her cousin grabbed him and said I just killed Henry Madsen and if you ever tell anyone you are a dead man. The long-held secret was relinquished with a single breath.

Was it winter in a room. Did the breath turn to smoke. Then snow. Then.

And who knows, maybe it is true. I find myself captivated by the invocation alone. And how the bridge becomes a symbol for transformation and crossing over—not only for Henry, but for the neighbor himself, and through this their two deaths collapse into a singular event. The bridge also serves as a crossroads and meeting point, a choice that must be made—to hold onto a secret or reveal it, to live or to die.

I think this could be a plot or grave, a straight story, no, could this be shelter from the wind, where I can place flowers and say a prayer for the dead, who remain here, who confound us.

XXI.

Some say that Ruth and her cousin wanted the money, that she ultimately took the fall for it, and that her cousin, wherever he rests now, had pulled the trigger. Though I have searched I can find no record of him, his name an absence, void, a place where facts empty themselves. In the court documents the defense lays witness to an unhappy married life, as well as her time spent in and out of hospitals on account of mental illness. Doctors suggested that she had dementia praecox of the paranoid type, as they called it, and she was later dismissed of the crime on account of insanity. She was only twenty-six when the murder occurred. The doctors subsequently confirmed that she had been, in their words, restored to sanity, and she was released from the State Hospital and free to start a new life, which she did, in Texas, where she eventually married a pastor.

XXII.

Looking out from the window onto a painted landscape I see the farmer standing with a pitchfork, his wife’s eyes darkening at the corner.

Is she worried for eternity to come.

The camera positions itself at once in the foreground and at a distance, searching for burial ground.

XXIII.

The dead who speak to us through history and, by way of extension, are heard:

My plans for the future, if I am released, and had the children, I would first establish a home.

XXIV.

Home is an elsewhere to which we attend, a myth stolen from the pages of a book.

XXV.

Gazing out on the harvested field like a blank screen, I see the movie playing itself out again. It could be anyone’s and only through coincidence and circumstance belongs to me. I am reminded of a passage from Sam Shepard’s play Buried Child, when the grandson tries to escape his heritage:

I was gonna run last night. I was gonna run and keep right on running. I drove all night. Clear to the Iowa border. The old man’s two bucks sitting right on the seat beside me. It never stopped raining the whole time. Never stopped once. I could see myself in the windshield. My face. My eyes. I studied my face. Studied everything about it. As though I was looking at another man. As though I could see his whole race behind him. Like a mummy’s face. I saw him dead and alive at the same time. In the same breath. In the windshield, I watched him breathe as though he was frozen in time. And every breath marked him. Marked him forever without him knowing. And then his face changed. His face became his father’s face. Same bones. Same eyes. Same nose. Same breath. And his father’s face changed to his Grandfather’s face. And it went on like that. Changing. Clear on back to faces I’d never seen before but still recognized. Still recognized the bones underneath. The eyes. The breath. The mouth. I followed my family clear into Iowa. Every last one. Straight into the Corn Belt and further. Straight back as far as they’d take me. Then it all dissolved. Everything dissolved.

XXVI.

Toward the documentary poetics of place which finds the aliveness of what lies hidden within the landscape, driving straight into the vanishing point.

XXVII.

All told, I think the neighbor’s role, however peripheral, warrants further examination. It might be a point of entry or doorway into a world which is still living beyond the frame, as any final moment or parting word could be. I said home is an elsewhere, but it is also a secret we hold on to. From what I can see, there is blood filling the roots and veins of the ground the house is built on.

XXVIII.

I take time for sleep on the journey just before and after. I see her face, and my family tells me it is my own, though I have Henry’s middle name.

XXIX.

A wedding portrait hangs above the empty fireplace in my grandparents’ basement. Their gaze is not unlike that of the farmer and his wife in Wood’s famous painting, and through gazing back we might discover a loophole in which we are permitted to return to a time. There also appears to be a stain in the lower right corner and a few thumbprints on the glass. An artifact living among and amidst our own small tragedies.

XXX.

Still we yearn for what is missing. I look into the mirror for the lack of what is found. An image infinitely regresses into the landscape reflected there, a hand carefully turning the mirror this way and that.

________________________

Notes:

“IX” takes a phrase from “The Stream By Hoover’s Birthplace” from the National Park Service.

About the Author

Julia Madsen is a multimedia poet and educator. She received an MFA in Literary Arts from Brown University and is a PhD candidate in English/Creative Writing at the University of Denver. Her first book, The Boneyard, The Birth Manual, A Burial: Investigations from the Heartland, (Trembling Pillow Press) was listed on Entropy’s Best Poetry Books of 2018.