Stephanie Strickland

Ringing the Changes

Counterpath Press, 2019

Print, 172 pages

Robotic nation False history spit out – Bikini Kill

But interruption already has its marks: this one $ and that $ – Anne Boyer

How she said, on Facebook, that she felt alienated in advance, and yet there she was, present and talking and questioning, and being in the room – Stephanie Young

. . .

I often stretch on a wood floor. If I perform the stretch correctly, my body will simulate some kind of recognizable shape. If I continue to stretch on a regular basis, my body will remember this shape, forming its arcs or bends with little to no mental prompting. The image of a shape is fused to muscle, an adherence that allows dance to occur.

I watch the few existing videos of famed dancer Anna Pavlova. This slim archive is comprised of silent film from the pinnacle of her post-World War I international fame.

I press functions on a keyboard to still the motion. I stare at the screenshots.

There is a ghostly aura outlining her body, presumably resulting from the poor quality of worn film digitized and uploaded to YouTube then screenshot and saved onto a laptop. This channel of transmission has caused blurriness and suffusion. I am reminded of Walter Benjamin’s notion of aura, how a reproduction can never adequately convey the contextual energy of the original; in this instance, that of the live performance.

Pavlova was a technically resolute dancer. Yet, her deification was not wholly derived from this pragmatic capacity. She was revered for the moments when her dexterity assumed a form incongruous with precision; the extraneous spill, the moment in which she appeared collapsible.

I return to the screen shots, realizing the fuzzy residue emanating from Pavlova’s figure inadvertently connotes the affectual impact of her performance; a reversal in which a mechanical mangling prompts an intimacy and closeness to aura. The images bear tangential and wispy lacerations; looking at the image leaves a bruise on my skin. It begins to appear as though geometry has no codifiable or concrete function as Pavlova’s body appears to supersede spatial maxims.

When I move my body, I feel stuck in a predictable rhythmic drone I must break. I begin to quietly misshape my pose. Beginning slowly, imperceptibly, perhaps by moving a single toe. I continue until the body is splayed out in all directions, a frantic deluge of velocity:

dissipation, havoc, shaking, collapsing, riot, revolt, subversion, compulsion, systemic rupture

. . .

The first lines of Stephanie Strickland’s Ringing the Changes refer to the theory of dance:

Dancers have spent generations thoroughly exploring the idea of “untrained.” Dance has exhaustively excavated the pedestrian, the amateur, the raw, and the unpolished. If anything, dance is now revisiting formalism and molding it into experimental structures.

Dance as a referent to Strickland’s lyric feels particularly resonant, as dance necessitates both a structure and an outburst. A dancer’s repetitious training allows for a constant re-telling, an ability to begin a narration then quickly receded, emerging with a slightly ruptured or frayed version. This methodology of repetition does not reproduce a homogenous monolith but rather exposes it through slight deviation. Strickland’s text is directly engaging in the encoding/decoding of structures, gesturing towards a praxis of the inter-textual, the multi- pronged, the ligamental rhizome compiled of oscillating connective bonds.

These poems, derived from code built around ancient church bell ringing sequences, do not adhere to but directly dismantle cohesive and precise narrative as a tenant of linguistic “mastery.” Code is a product of a capitalistic structure propelled by an ideology of ostensible progress, therefore performing its own iteration of a narrative arch. Strickland employs code as a means to subvert its power. Each poem is formally parceled, containerized as prose blocks that mimic the streamlined narrative it seeks to dismantle. Or to read this work as one long poem is to consider the ways in which the epic is warped and distorted; the hero’s journey is no longer a cumulative performance of gilded attainment but rather an aggregation that results in a cyclical falling and looping. This work harbors an undulating motion, a seeping-through-the-fingers. The process of logistical code accumulates content which these poems then emanate as a warm murmur or soft gesture, a performative utterance.

Is background noise the ground of our being, as every message, every call, every signal must be separated from the hubbub that occupies silence, in order to be, to be perceived, to be known, to be exchanged?

Code can be understood as the product of an apparatus following the dictums of a post-Fordist economy in which machines further alienate the human psyche by auto-producing language and curating a new semiotic structure with differently-sensitized emotional registers — SMS autocorrect, google auto-complete, factory machine code — often leaving a corollary sensation of dull prodding pain. Strickland writes: Whatever is shown on screens today is mostly numbers posing as people. Machines algorithmically anticipate and transmit language, therefore instigating a new dominant mode of communicative practice, an algorithm that is often acritically ingested with pleasure.

Strickland confronts this system in which technology is instrumentalized as means to dissociate, compress, and exploit. Her lyric does not disregard technology, as her work itself hinges on its generative capacity, but rather challenges those wielding it as a conduit to oppress. By seizing the technology herself, Strickland engenders a new kind of agency and the ability to re-signify language flattened by a hegemonic machine.

Is a human-machine relation more fundamental than the capital-labor relation?

How to touch, bleed, weep, scar amid the incursion of machines for the purpose of political domination?

. . .

I’m continuing to work against the disappearance of handwriting.

Strickland’s process is a poetics of intervention, she is engaged in hacking. I am somewhat apprehensive to use the word hacking, as I now think of its flippant applications (the perceived whimsy of the corporate-sponsored hack-a-thon). Yet, the practices of insurgency, fugitivity, and insurrection remain resonant ideological threads in relation to this term. Strickland is working on the machine yet dutifully rigs it, dismantling its capacity to subjugate.

This form of hacking alludes to an intimate, material experience of sculpting or reassembling. I think of collage and the specific relationality it produces between maker and materials, an embodied and intuitive collation. I am reminded of Susan Howe’s Debths, in which the poem is wholly merged with collage, forming an archival map that insist upon the vitality of the archive, memory, and embodied history within discourse. I think of Howe’s title, its various iterations or gleanings: depths, ebb, debt and how it is performing a manual code, or anti-code, through an a- grammatical blending. Howe’s book compiles angular, textual structures; poems that one desires to peel off the page and hold. These architectural formations coexist amid sonic, thematic, and contextual dissonances.

Touch is entwined and flows in both directions.

I realize that Howe and Strickland are engaged in parallel projects. While Strickland’s text formally appears to engage in a streamlined consistency, it dismembers the apparatus of “quality control,” its entrails oozing out from underneath.

The Earth is on the move. You can’t join from the outside. You come up from under, and you fall back into its surf.

Strickland’s uniform prose blocks, augmented by grayscale marginal numbers, initially indicate a system, mimicking a referential bibliographic text. Yet, as the work progresses, the discernible numeric code disintegrates for a reader not privy to the micro-technicalities of the code. The numbers can be re-signified as a tidal push, a wave on the peripheries that has the potential to seep inward and stain the code-informed text. The very mechanism of the code, the numeric notation, undoes itself.

As if dipping the book in a puddle or pool, a watermark spreads across the page. As Howe writes: There. Messages flow through clear lake water and yes, gravity pulls matter together to form a cosmic web. Instead of extracting and touching Strickland’s poems, one desires to be engulfed by them.

. . .

Strickland conjures a form of code-making that is constantly in motion, unable to pin down. This enables a fluidity to emerge and resist its potential to be co-opted. In this sense, Strickland’s work is engaged in a DIY guerilla tactic; just when one thinks the code has been cracked, that its logic can be seized, the technicalities of the code have already transmuted. I think of Kathleen Hanna’s band, Le Tigre, often dubbed the “feminist party band.” In the late 1990s, after the breakup of her emblematic Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill, Hanna turned to electronic music. Le Tigre seized the available technology (synths, projectors, drum kits, samples) and employed them to make politically-radical pop songs. This transition from Bikini Kill to Le Tigre was particularly astute; just as punk was being commodified and mass-marketed, Hanna decided to form a pop band and exist as an impostor within the dominant music market. Le Tigre’s coordinated outfits, synchronized dance routines, and sonically-anthemic rhythms produced a repetitious hum embedded with cutting shards of the politically radical. They sing: My data says “large” / But what I see is small / Text reads “Big Danger”/ But this just looks tired.

Strickland has employed an analogous strategy via poetics. Her code is integrally rooted in the sequences of church bell ringing, a practice both regimented and taut – administered through a monolithic entity – but also tethered to the deeply somatic terrain of ritual, spirituality, and communal awe: We have to admit that machines don’t deal with language in the way we do. I suggest we surrender the opposition between syntax and semantics and instead take up the concept of relation. She is constantly engaged in a negotiation between the fraught ecologies of a system and its rupture; their generative combustion.

. . . Why not just make tunes?

Strickland’s work engages with structure to examine the potentiality of occurrence between each pronouncement of orchestrated sound: the silent subspace, the cracking aches that reverberate in an oscillatory zone deemed void or resigned to the “incoherent” abstraction of infinite regress.

On the notion of subversive tectonics, I think of Fred Moten’s undercommons. He writes, This art is practiced on and over the edge of politics, beneath its ground, in animative and improvisatory decomposition of its inert body. It emerges as an ensemblic stand, a kinetic set of positions, but also takes the form of embodied notation, study, score. It’s encoded noise is hidden in plain sight from the ones who refuse to see and hear.

As in:

The notion of Strickland’s undercurrent or striation is one in which phenomenologies seep, enmesh, tighten, pull, lean. These multiple bodies, their positionalities, are evoked through a tactile rubbing next to, a form of productive friction that yields kinetic energy.

What are the consequences of setting traditionally modernist abstract carved stone (Barbra Hepworth), next to twisted and wrapped yarn tied in a cocoon around hidden objects (Judith Scott), next to a scroll unfurled from a vulva (Carolee Schneemann).

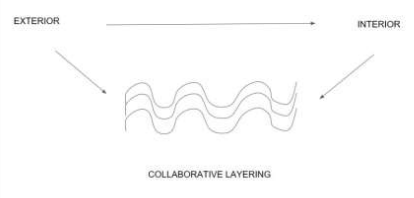

Strickand’s work is concerned with kinship and its textual directionality. Her striation is created by a literal weaving of writers/theorists/artists: Donna Haraway, Hito Steyerl, Fred Moten, Aria Dean. Through this visceral act of collaboration, Strickland thoroughly materializes the often- hyper-conceptual language of postmodernism that risks disembodiment and trivialization: network, rhizome, de-territorialize, fraying. She doesn’t engage with these terms frivolously, but is concerned with their tangible catalyzation. I imagine a visual representation of Strickland’s textual cartography in which the contextualizing axes are nebulous, a mapping in the sense that it directs possible configurations of being while also conjuring an anti-topography that conducts echoes, vibrations, and undulations. The map is largely considered to be an indisputable document as in: THE BORDER LIES HERE. Strickland’s topography disputes the purported fidelity of the map by establishing alternate channels and insurgent undercurrents.

. . .

Communities can have the character of open sets and textured gradients more than crisp boundaries.

Ringing the Changes conjures a medi(tation)ation of/on technological social-political schemas and elucidates an altered rationale for the implementation of formulaic process — the flourishing of a pulsing, jagged ecology.

A gesture of alternate mapping, Strickland’s work constellates a non-hierarchal grid that employs technology not to regulate and structure the amorphous relationalities of the material world, but rather to place these kinships in new modes of correspondence and interrelation via a theory of musicality. This musicality is an aural-textual performance hinged on in betweenness through the interval — its simultaneous silence and cacophony, its polyvocality and improvisation.

It is more flexible and ultimately more effective to think of (the continuum of) space as a manifold “glued” or “quilted” of subspaces, such as those covering each point, rather than as something continuously constituted by points. Points come later, topologists sometimes say; spaces come first.

This is a gesture of radical world-building initiated on a micro level:

in dirt in data in grit in numbers in urls in murk in germs in metal in shards in hard drives in tenor in word processors in grids in sprouts in cracks in maps in striations in water marks in threads in voracious tides that furl at the edges of paper.

. . .

[postscript: re: my body reformed as radical current]

Infatuated with the screenshots saved on my laptop, I began to write poems. I digitally overlaid the text of top of the image. I left the text box translucent, hoping to create a synthesized text- image. In relation to a still of Pavlova on her knees, arching her back as if in a flagrant wail I wrote:

in the ocean, you turn your head and say, “the mp3 file has not finished downloading”

Someone questioned my reference to technology and its occurrence amid an instance of seemingly unrestrained emotional frivolity. I did not know how to respond.

Now, I feel as though I could respond via Strickland’s lyric. I suppose I could have said: my body was responding to the noise.

About the Author

Erica Ammann is a poet from New Jersey who currently lives in Brooklyn. She earned a BFA in Writing from Pratt Institute and is the Social Media Director at No, Dear Magazine. Her work has also appeared in Deluge and Fanzine.