M. Forajter’s Ars Necrotica

Technicolor Death Dress

Ecological terrorism, Chicago, Chernobyl, Dr. Mousseau, and Hae Min Lee, a teenager from Baltimore, MD, who was murdered in the winter of 1999.

Today I am thinking about ecological terrorism and dying planets and our legacy as human beings. I am thinking about Chicago and leaded soil and tigers and beautiful things we ruin on purpose.

Today I am thinking about the Chernobyl nuclear accident and its wider cultural impacts and denialism, which is as potent as an intoxicant I can think of. I am thinking of scientists and research and the name Dr. Mousseau, like the French for sparkling wine. One thought bleeds into another. A biologist melts into foam, froth— the mousseux of Bubbly Creek on Chicago’s south side, a branch of the city’s river where the infamous slaughterhouses of the 19th century dumped their horror-waste of blood and bile and sinew; centuries later, it’s sediment still thick with the fatty sluice of a million slaughtered cattle, rots into soapy foam.

Yes, I am thinking of this image. Of my home. With this image I am everything and must not speak just from memory or personal trauma, but instead from a localized trauma that places the self within a wider context… and also contextualizes local traumas that may be too wide-ranged for the human soul to truly reckon.

That being said, taking the macro and making it micro, so that we sing within it.

X

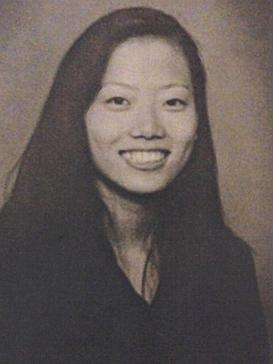

The death of Hae Min Lee, a teenager from Baltimore, MD, who was brutally killed in the winter of 1999, sings within me in this way. Senselessness in micro. One person. A tragedy we can digest and make part of ourselves.

Hae Min Lee’s body was discovered in a large wooded nature reserve two months after her disappearance. Her body was discovered when a local maintenance worker, dubbed “Mr. S” to protect his privacy, walked into the woods to piss. As Mr. S. recollected, he was suddenly hit with the urge to urinate when driving between home and work. He quickly pulled to the side of the road and entered the woods. While looking for a suitable location, Mr. S spotted human hair lying on the ground. He immediately informed the police…

What else is there to do? Make a phone call, become one with ooze; to mourn a dying planet. I walk past fields and imagine being of the field, the way dead bodies become part of their environments, the way they melt into the grass or boil on concrete. Is this moving from subject to object? To lay oneself out in a field and feel the grass all around you, feel the earth and the small rocks lodged under your spine

Accretion, accretion, accretion.

I think about Hae a lot. I think about the unfairness of her life. About the fact of her death. I think about her grieving family, and the horror that is her sensationalized end.

She is one person. I think this is how this story must begin. Questions, a reckoning… One death.

Yes, the micro to macro. A dying planet. A dead girl in the woods.

More importantly, I ask myself— what is the necessary point? Who have I killed to write this down? How long do we have left?

X

When thinking about Chicago and its ties to Chernobyl, about ecological disaster and poison and fault, instead of activism, it lead me to write garbage.

Unidentified workers take radiation measurements in the area surrounding the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine.

In fact, I wanted to start this project by writing about Chicago and Northwestern Indiana’s industrial corridors, places with which I am intimately familiar and for me best represent the damage of industrial contamination on communities. Both are communities with long histories of industrialization, factory labor, capitalism and New World Order. I have been thinking about the ecological effects of pollution and contamination for a long time, so much so that it nearly took over my previous writing project, Interrogating the Eye. It was surprising that so much vitriol regarding poison and pollution was coming out of me (so much that I named the final section of the manuscript “A Horrible World,”) when Eye was firmly anchored in ideas about art and religious vision. Toxicants seeped into my writing and poisoned any concept I had cultivated of the divine. This echoes my life directly. I grew up in these same contaminated places after all, and experienced the damage pollution can do to bodies and locales. I suppose in all my writing about artistic and religious fervor in my previous project, in all my calls to the heavens to grant me with similar furious purpose, I was granted it by way of my childhood heavy metal toxicity.

But the events that occurred over the last century in these industrial corridors are boring because they are identical to what we see replayed everywhere in America regarding marginalized bodies and corporate greed. It is a song that will not stop, infectious as the fermenting bacteria dumped into our drinking water: which bodies/land are viewed as valuable and worth protecting, and which can be exploited for profit.

While the recently discovered leaded soil of Northwestern Indiana and the after effects of the steel mills on the far southside of Chicago are awful stories that deserve telling, I feel myself worrying over ontological issues instead. I worry that these catastrophes are unsolvable because they are ecological. That our connections to them are simultaneously too tenuous & intense because we are human beings. We are the problem and yet outside the problem as a matter of control and perception. Take for instance the Chernobyl disaster: how can man possibly reckon against an isotope? Against the 10,000 years it takes for radioactivity to decay? Humans will be smears on an intergalactic windscreen by then. It’s totally beyond us.

Consider researchers Møller & Mousseau, the biologists who melt in my imagination. Controversial figures in the scientific community but important because they’ve entered and spent more time traversing the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone than any other researchers, which may explain the differences in their conclusions regarding long-term low-dose ionizing radiation exposure. (They claim it does more harm then we currently understand.) Many other researchers looking into the ecological impact of the world’s largest nuclear disaster have limited their studies to brief helicopter flyovers during which they conduct aerial spot-counts of animals. This presents obvious problems regarding fauna who may not be large enough to see from a distance, as well as the practical matter of recording minute changes in flora, soil, and water.

Furthermore, many scientists rely instead on data and simulations garnered from outside sources in order to formulate conclusions regarding long-term nuclear impact on living creatures. While meta-analysis and simulated data projections are useful and respected scientific tools, there is something to be said for actually witnessing a physical space. This is a lesson we can take from cold case investigators who understand that actually visiting a crime scene even decades after its occurrence, like that of the case of Hae Min Lee, can vastly shift perspectives.

X

One girl melts to foam. Becomes part of the litter on the forest floor. Becomes one with the locale. Her family doesn’t need to know about skin slippage, lividity, insect habitation.

They know her end from her absence.

But we do; we need to learn about every strip of skin. We need to be forced to understand.

X

From photographs and common sense, one would assume that Mr. S, who found Hae’s body, wouldn’t have to move a far distance into the woods to take a quick pee. A man can simply pick a tree and move behind it, even when close to the roadway. One might think how suspicious it seems that Mr. S moved 100 feet from the road into the woods in order to relieve himself, then happened to walk upon the body. However, after visiting the site several investigators remarked that the woods along the roadway are sparse; that the brambles there provide no sense of privacy; that the 100 feet Mr. S traversed is the minimum sensible distance for any sort of coverage between the trees; that with the rush of cars still plainly audible, 100 feet didn’t feel very far from the road at all.

Mr. S was a problematic figure in Hae Min Lee’s case; he had an extensive record of indecent exposure and even admitted to drinking while driving in the park that day. While many pieces of evidence eventually came to rule out Mr. S as anything more than a man who stumbled upon a terrible crime, the view of the road from 100 feet inside the woods still seems the most clarifying.

X

Yes: being at the scene of the crime can help us widen our perspectives but it also presents new, more difficult ontological problems. What happens when we proximate ourselves to tragedy?

Hae Min Lee

How does it actually help? Does it give us the clarity of vision to realize the “truth” of things? Does it empower us with moral fortitude; give rightness to our convictions? Motivate us to “do the right thing”? What actions can we take as human beings with our new, more truthful perspective? What does it honestly matter if Møller and Mousseau discover the exact nature of prolonged ionizing radiation on living creatures if the damage can’t be reversed? What does finding Hae Min Lee’s killer mean to Hae Min Lee?

This is the source of my doubt. Ecological concerns are often countered with talk about environmental justice. What does justice mean to the corpse? We’re far past that, just as far as Hae Min Lee. The problems created by the toxicants, pollutants, contamination, etc. that we have forced on the planet and thus on ourselves has turned this age into that of the Anthropocene, the age of humans. However, our supremacy is necrotic, as are all supremacies; a self-inflicted malady that eats away. Sometimes I feel like all that is left to do is create necrotics with our radioactive scraps. When I say necrotics I mean necro + erotic; I mean MRSA, too. Necrotics don’t just eat away at the human face (they do) but also the world’s. All the turtles are stuffed with plastic straws and the tigers are inbred into infertility and soon all the heads on Easter Island, which seems to have been birthed from rock itself, will be under the sea and away from the eye of God.

X

The concept of dancing along the disgusting edges of the beautiful is emphatically not mine but instead is the child of Joyelle McSweeney in her critical work: The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults. I must confess that I did not understand a word of this theory, though I poured over the book many times, until I started paying closer attention to ecology and human disaster and realized they were irreparably intertwined. The Necropastoral that McSweeney defines is the Art of the Anthropocene; the only avenue left we have to communicate as conscious beings. We’ve forcibly made ourselves Death’s sweethearts by romancing Pestilence. If the goal was total mutation through necrophilia, it’s worked.

If the Necropastoral is an aesthetic then I’ve made my necrotics using McSweeney’s dress pattern— I’ve created a technicolor Death dress in homage to McSweeney and a dying planet. I’m engaging with the Necropastoral, and spitting out rot. I’m showing off.

Does necrotics simply mean suicide? Do we poison ourselves for fun? More, I think my necrotics are like when 17th-century aristocratic ladies used lead makeup to paint stars and hearts over their syphilis sores; when doctors of the same era would slice open a vein to cure a fever which was contracted from feces contaminated water. Blithely poisoning yourself is a necrotic. Chain smoking while wearing sexy red lipstick and trying not to imagine your rotting lungs is necrotic. Necrotics are similar to vasectomies but closer to infanticide. To sugary breakfast cereal. Tigers in cages are necrotic, as are the little posted signs in front of their exhibits saying, ‘this is for their own good.’

What is useful about the Necropastoral, and thus my necro-baubles, is that it offers an outlet to my anxiety about ecology outside of throwing myself into the ocean. As noted previously, my anxieties about the ecological terrorism perpetrated on my childhood home move me to think beyond clean up or prevention of future incidents. Change has already rained down on the planet. When I remember that the global annihilation clock is ticking, it scares the piss out of me. We’re beyond prevention; peeing yourself sounds like a reasonable response. Let me say that I hate my lead poisoning and my brother’s lead poisoning and my mother’s cancer and my grandfather’s cancer and all the suffering these maladies have caused. I hate when it happens to anyone. I hate the coming devastation of climate change. But inside the Necropastoral of the present, I must not speak just from memory or personal anxiety but instead from a trauma that places the self within a wider context of the past and the future and nothing. Also within traumas too wide for the human soul to truly understand. & I have so many notes on these traumas, more than what I can make accessible. Murders. Mutilations. Contamination readouts. Lead poisoning. Thyroid cancers. 50% more miscarriages in the year following the Chernobyl accident. Belarus. Ukraine. No conclusive evidence of substantial impact on wildlife. Wild boar. Many wolves. The pines that turned red overnight. Slight asymmetric measurements. Don’t drink milk or eat tomatoes. What do I do with an astrological report that blazes like

area gross actual sunflower fortitude nuclear age pollution contamination end of the world gross body ecological anxiety HUMANS, HUMANS, HUMANS

Do we need our toxicants spelled out to us? Is that really necessary? It is so clear that an ocean full of plastic is wrong. It’s clear that we’re full of shit. I don’t know. Maybe. Honestly, when you live in a garbage dump, what else is there to do besides make things out of garbage?

In this light, necrotics reflect what we do to ourselves— a point of purposeless poisoning— an art that does nothing, does not benefit. It’s a death knell, not a news report. You can only form things from the things you know. I suppose I have to create then, despite the decay. But a necrotic is also a statement of dying. So my piss-pants become a necrotic, especially if I nail them to a wall.

About the Author

M. Forajter is the editor of Tarpaulin Sky Press & Magazine. Her work has been published in several magazines, including The Journal Petra, Court Green, Burning House Press, Deluge, and Witch Craft Magazine. Her chapbooks, WHITE DEER and Marmalade Girl, are available from dancing girl press. She really likes Nirvana, werewolves, and medieval art.

About the Author

M. Forajter is the editor of Tarpaulin Sky Press & Magazine. Her work has been published in several magazines, including The Journal Petra, Court Green, Burning House Press, Deluge, and Witch Craft Magazine. Her chapbooks, WHITE DEER and Marmalade Girl, are available from dancing girl press. She really likes Nirvana, werewolves, and medieval art.