Kelly Krumrie’s figuring

An Interview with Miranda Mellis

Figuring is a monthly column that puzzles over (to figure) and gives shape to (a figure) writing, art, and environments that integrate or concern mathematics and the sciences. This month’s column features an interview with author, Miranda Mellis.

Kelly Krumrie’s figuring

An interview with Miranda Mellis

Figuring is a monthly column that puzzles over (to figure) and gives shape to (a figure) writing, art, and environments that integrate or concern mathematics and the sciences.

In 2008, I served as an intern for The Encyclopedia Project, a three-volume collection of prose and visual art organized as a reference text, edited by Tisa Bryant, Miranda Mellis, Kate Schatz, and Katie Aymar. Each entry is a response to a word, and the volumes are arranged alphabetically, including references to each other across volumes. There are lists, images, short stories, essays, and indices. Rosmarie Waldrop on collage, M. Nourbese Philip on carnival, Sawako Nakayasu on Japanese ants, Samuel R. Delany on Hölderlin… Michelle Tea, Joanna Howard, Fred Moten, Dawn Lundy Martin, Eugene Lim, Thalia Field… a collection of exciting and innovative work organized in a curious, looping zigzag of terms and arrows.

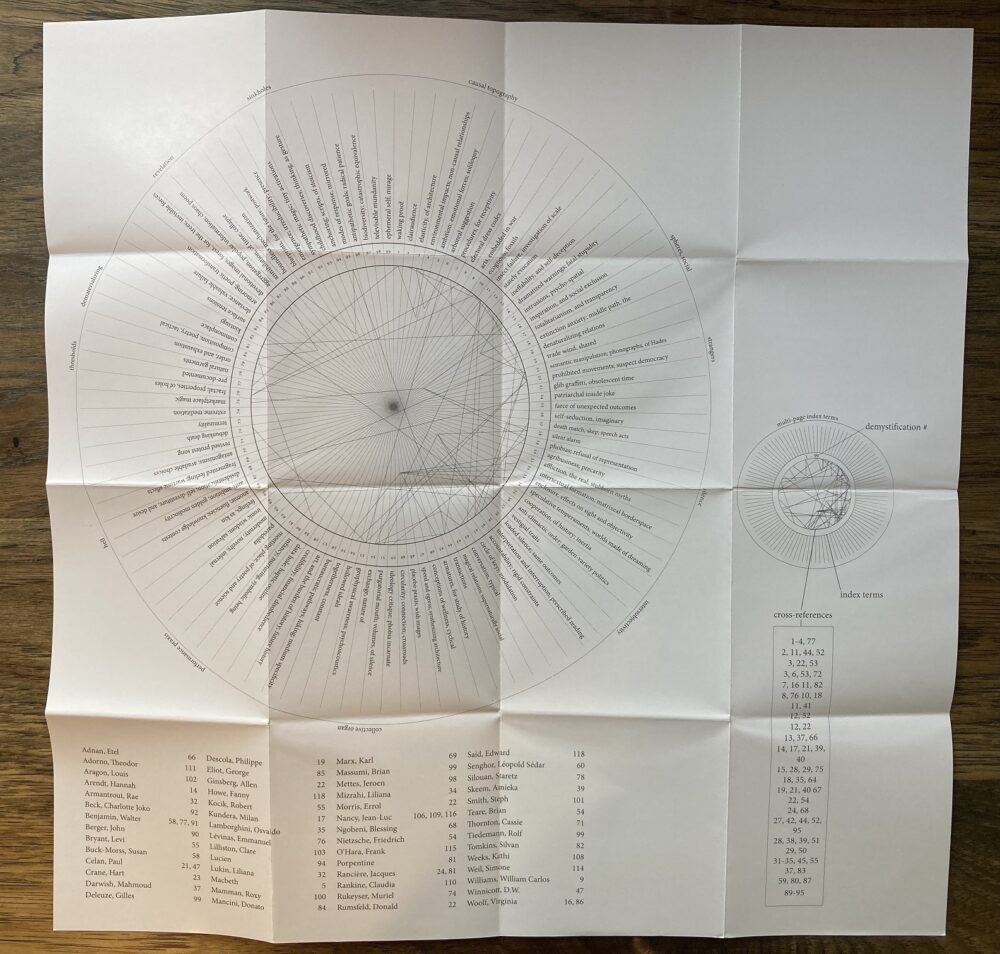

Reading and working (even briefly) on these volumes inspired and challenged how I thought and (some thirteen years later) continue to think about art and information. (In fact, the second volume, F-K, has (appropriately) been propping up my laptop on most Zoom calls over the last year.) It’s no surprise to me that the latest book by Encyclopedia editor Miranda Mellis includes a folded up poster of Katie Aymar’s “visual index” for the work and that the back cover genre listing reads Poetry/Philosophy.

Miranda Mellis’s Demystifications (Solid Objects) is kind of like a little encyclopedia. Ninety-nine numbered texts take a variety of forms: observations, quotations, jokes, anecdotes, lists, essays, and poems. What’s mystifying to me about Demystifications is how all these forms exist together in their brevity (many of them are between one and five sentences), lightness, and gravity, and how the work refers: it’s a text in and outside of itself. Below, Mellis and I discuss the act of demystification and collecting items from cognitive fields.

***

Kelly Krumrie: As I was reading Demystifications, and flipping back through and rereading once I encountered the indices, I kept wondering about the shape of information in this work. How would you describe the relationship between fact and form here?

Miranda Mellis: I think of the index that Katie Aymar made for this book as an interpretive response that sets it off, or sends it rolling elsewhere, though it is also functionally referential, something you can use to go back into the lines. In a way, the whole book is an index, too. Carol Maso advised “Make notebooks, not masterpieces.” As for facts, to demystify would seem to be to negate what is not factual, in order to get at what is. Yet a fact is always unstable – a contingent assemblage reliant upon shared patternicity. The shape of information in this book is open to reshaping. I read an article the other day in which a developmental biologist said, “If we could understand what three-dimensional shape really was, we could do almost anything.” Whatever is three-dimensional has spaces, edges and vertices. I don’t try to represent three-dimensions, but gaps and elisions infer other (indeterminate) points beyond the text.

KK: I am fascinated by this biologist’s sentence—that we don’t know what three-dimensional shapes really are? Poor Euclid! I like thinking of Demystifications itself (not to say that the indices aren’t part of it) as an index because of the “pointing” operation of the word. The pieces point to one another thematically and directly (and by the very fact that they’re published together in a book), and your use of quotations points out to other texts and the people who wrote them. Can you say more about the role of quotation/citation in this book (or in your thinking in general)? And what might be demystifying (or mystifying, or re-mystifying) about the act of reference?

MM: Demystifications, in addition to whatever else it is, is very much a record of what I was reading at the time I wrote it, as well as who I was talking with and what I was listening to. Here, the spoken or sung is given equal billing with the written, albeit the spoken has a primacy that the written doesn’t, arising, as the spoken does, spontaneously (tweets and texts excluded, as they can partake of the spontaneity of speech).

Every text has an index. Sometimes this fact is hidden or effaced, other times explicit and foregrounded, but one is always beholden to other writings and writers. In that sense every text no matter how primary its status is a secondary text! Even the most ancient stories, the creation myths, would have been secondary iterations of their initial oral forms. In Demystifications the index is on the surface. I had in mind the “commonplace book” as a form. Walter Benjamin intended to compose an entire book out of only quotations. The Arcades Project stems from that aspiration, a collaging of citation and commentary, an enactment of reading: writing as reading, that is.

KK: I’d love to read anything you’re willing to share about the process of writing Demystifications. I’m particularly curious about your movement from fiction to poetry / a more fragmented form.

MM: In the process of writing Demystifications, I found myself in a strange phase, mentally, of being hyper-sensitively attuned to what I came to call the gesture of demystification. Perhaps I could liken it to bird watching or collecting shells on a beach. Some kind of cognitive basket recognized and “caught” demystifications over a period of time. They would emanate from a text, or from an experience, an observation, a conversation, a moment, precipitate out of the generalized pool of experience registering for me as, specifically, “a demystification” as I was conceiving of it. When that would happen I would write them down. The ordering is roughly related to the order in which these events of recognition occurred. It wasn’t a plan, rather each one was spontaneous, like something you pluck from a field, only in this case, a cognitive field. In this sense a demystification in the context of this book is a particular, invented species of the genus “demystification.” I don’t claim that these are objective demystifications, rather they are poetic, and I demystify demystification itself with one quote from Jacques Rancière (demystification #22).

KK: I certainly had the “commonplace book” in mind as I read Demystifications, and that’s part of why I opened this conversation with the idea of “shape.” There are a few organizing principles at work here: the demystifications are numbered 1-99; there are indices; there are quotations. Yet, not unlike how Benjamin’s convolutes within The Arcades Project are alphabetized, Demystifications, through its multiplicity of arrangements, doesn’t make a defined shape, as you say—even with Aymar’s “visual index.” Benjamin uses the word constellation quite a few times in The Arcades (though, because I’m reading it in translation, I can’t be sure), and I like to think about that word in relation to that project or this one: a constellation is an interpretative shape-making from objects that have no relationship to one another. We give them a relationship, based on our point of view, by likening their apparent arrangement to an image of something known, like a square or a lion. I’m not sure I have a question here, but lately I’m attracted to writing that makes the writer’s “cognitive field” explicit, and I’m curious about what readers do when they encounter writers’ collections of shells.

MM: Like a spontaneous walk where one has heterogeneous encounters that don’t necessarily relate except through your sense making, certain texts can be opened and started anywhere, and that’s true of Demystifications. Though it has a logic to its patchwork, where questions or ideas do echo and resonate, it’s brief – a thumb-piano opera.

I have always been taken with The Arcades Project as the reading experience that comes closest to the feeling of reading as wandering in a library, the convolutes as stacks, a flânerie of reading. But pack your water and your sleeping bag because it is going to be an infinite walk . . . he composes a walk that never ends, makes spaces that open and never close. Because of his interest in Jewish mysticism perhaps this mode can be related to a Jewish conception of exile as going forth without a return, a liminal enactment of, as Jewish anarchist writer Eli Damm puts it “the divine, in exile with us” (from an unpublished essay, “Atah Bekhartonu On Chosenness: In Golus And In The Space”). This ethic of divine exile does not entail return and refuses the correlation of identity and state. Of course this reference to long walks brings to mind the sorrow of Benjamin’s suicide: having made it to the border of Pyrenees, the story goes, he despaired of eluding fascism, not knowing he was about to escape (though Stephen Schwartz believes that he was assassinated).

KK: The demystifications themselves are quite small, and many moments in Demystifications are light and airy: humorous, aphoristic. For example, the beginning of #29 reads:

Phobias:

Surveillance

Narcissists

People whose legend precedes them

Show trials

Indoor parking lots

Off-gassing

Predators

Bleach

Drones

Self-righteousness

Subtlety

Lack of subtlety

I laughed out loud at “indoor parking lots” and “off-gassing.” At the same time as being brief and funny, the observations and quotations within Demystifications can be serious and complicated (e.g., Benjamin, Rancière). Is brevity a product of the spontaneity of the book’s making? What is the role of humor in demystifying? Aphorism?

MM: Yes, I think that’s right: brevity is connected to the spontaneity of an arrival/sensation/gesture, coming and going like a bird, without elaboration. Another way of putting your question is: what is it to be taken by surprise? In some cases, it’s to make a new sense emerge. For example, let’s say you tell me, I’ve had a long day. I might interpret that as meaning you’ve had a hard day. But if then you say: . . . because I got up early, then that’s giving the expression a new (if obvious) sense: Getting up early is the cause of a long day (demystification #1). Here the demystification is the retort of a person with a nocturnal chronotype, to anyone who thinks getting up early is especially virtuous. No: it’s simply the cause of a long day. There is the subtraction of moral judgment – which is always extra. The epigraph from Fanny Howe describes how subtraction allows things to “add up”: “How can something add up, when it is only conceived and then understood in reverse? By subtracting until a lot of it is gone.” Subtracting what? Subtracting habitual sense-making, including common sense and received moral judgment. How is metaphor, which works through transference of meanings, subtractive? In demystification #12 “Resentment is the dried blood of wounded virtue. The Utah of emotions.” If you know what Utah is, what dried blood is, and what resentment is, it rings true: the state of Utah is hot, dry, salty and exposed, and so is the state of resentment. Here is a metonymic progression – resentment, blood, Utah – that laughs a bit at resentment (so epic and yet so undignified) by subtracting its operatic self-seriousness, while giving it its due. In demystification #41 the book is described as a key ring, a circle of keys, which refers both to door keys and the circle of fifths (“dictionary of all keys”). The prefix de- denotes reversal, undoing, conveying down or away – so Demystifications plays in the key of de: de-idealization, de-construction, de-pression, de-creation, and de-legitimation. And I hope that tenderness and compassion is the result.

KK: You engage with science, conservation, climate, ecology, etc., in Demystifications (I’m thinking specifically of #97) and in your teaching. How would you describe your relationship, as an artist and a teacher, to the sciences?

MM: In the spirit of the book and our conversation, I’ll answer with demystification #61:

For Muriel Rukeyser to grow meant to move past

false barriersShe wrote that

The drives of poetry and science share in

open-endedness over the fatal telos

of instrumentalityShe wrote that

the world of the poet

is the scientist’s world. Their claim on systems

is the same claim.

Their writings anticipate each other;

welcome each other;

indeed embracePoets and scientists give themselves closely

to the creation and description of systemsIt is not a matter of using the results of science,

but of seeing that there is a meeting place between

all kinds of imaginationPoetry can provide that meeting place

Index for “Demystifications,” created by Katie Aymer

About the Author

Kelly Krumrie‘s prose, poetry, and reviews are forthcoming from or appear in Entropy, La Vague, Black Warrior Review, Full Stop, and elsewhere. She is a PhD candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Denver where she serves as the prose editor for Denver Quarterly.