Kelly Krumrie’s figuring

On Fractals, Part 2

Figuring is a monthly column that puzzles over (to figure) and gives shape to (a figure) writing, art, and environments that integrate or concern mathematics and the sciences. This month’s column looks at the connection between language and fractals.

Last year, I was researching for a presentation on Gertrude Stein and mathematics, and I came across an article describing Stein’s use of repetition in Melanctha as “fractal.” The author, Juana T. Guerra de la Torre, selects a word and counts how many times it appears in each paragraph. She then graphs the frequency, sketches a wave to illustrate a pattern, and argues that the pattern repeats at different scales. That is, the number of times the word repeats in paragraphs across the text is fractal.

I describe a few types of fractals in Part One of this essay. A mini-definition is “an object or quantity that displays self-similarity on all scales.” I am curious about how we use mathematical analogies to illustrate something about literature—how close we get to the “real thing.” Why are these illustrations helpful? What do they help us see?

Counting Stein’s repetitions of a word is an interesting choice considering Stein argued that her repetitions were not exact repetitions. A word appearing in a new instance is not the same word: “Then also there is the important question of repetition and is there any such thing. Is there repetition or is there insistence. I am inclined to believe there is no such thing as repetition.” If we take this literally and to the extreme, it is impossible to count repetitions of words in her work. Without counting, there is no graphable quantification through which we can see a pattern. So there is no pattern, and the text is not fractal.

This feels like a weird claim for me to make, maybe a wild one, because anyone who’s read Stein knows repetition is kind of her thing. (As simple as it is, repetition is probably my favorite literary device.) And Stein’s poetics is her own, and I wouldn’t want to apply it to others’ works. But the idea of counting words (and how and when words can be counted) has led me to wonder about the boundaries of repetition in literature.

While reading Lisa Robertson’s recently published first novel The Baudelaire Fractal, I wondered where the fractal was. I know we use words like “fractal” as metaphors all the time, that it’s not unusual, and we don’t always go digging for their literal manifestations (or write essays about them). But the definitive article in the title and the novel’s repetitions and iterations, layering of time and space, the entire premise, really, made me question the word’s use more than I might ordinarily. Is the novel (like) a fractal?

The nature of fractals (in any form) is scalar reiteration, a repetition of a shape or an equation with successive inputs and outputs. How can literature be fractal? It should probably include repetitions on various scales. But what are the edges of literary repetition? What can be counted? How can what’s counted get bigger or smaller while remaining the same?

The nature of fractals (in any form) is scalar reiteration, a repetition of a shape or an equation with successive inputs and outputs. How can literature be fractal? It should probably include repetitions on various scales. But what are the edges of literary repetition? What can be counted? How can what’s counted get bigger or smaller while remaining the same?

I am most interested in these questions with regards to prose works because prose doesn’t lend itself so easily to counting. I am not sure what the units are: word, phrase, sentence, paragraph, section, chapter, book?

I started asking for recommendations of texts folks found fractal, and ones with heavy repetition, and I pulled books off my shelves, making piles all over the floor. I wrote an essay parallel to this one on Elizabeth Bishop and crystals. I drafted prose poems out of lines from others. I copied and pasted parts of essays into each other, split this project in two, oscillated about my room. I am lonely and strangely bored here, Zooming with students, looking out the window, baking, like you. I should have written about exponential growth, right? I am so hung up on fractal being a pointless question. I know it isn’t. But it also is.

I’ll throw some examples in the air to see what transformations they make, what shape:

1. Alain Robbe-Grillet’s work came to mind first, especially the novel Jealousy and the film Last Year at Marienbad. However, while these works include repetition on a gross scale, that is, they kind of loop the same scenes over and over, I wouldn’t argue that scenes or descriptions reiterate across scales, forming a patterned shape. I wouldn’t try to graph them. Juan Jose Saer’s novel Nobody Nothing Never does something similar: there are alterations in iterations; the novel feels trapped in a loop of no time; the same thing happens again and again. But repetition alone is not fractal.

2. Renee Gladman’s collection Calamities is made of short sections that each begin “I began the day…” but each entry is different, though some refer to one another. We could think of “I began the day” like a function machine: something goes in (this part is unwritten) and through the process of “I began the day” (imagine the phrase as a little machine transforming the input), we get the entry that follows as an output. This could be fractal? I am not sure about scale though: that the pieces perform a repetition micro- or macrocosmically. I might argue that they’re changing shape while starting from the same coordinates, more like a topological permutation than a fractal one. Or a group of entries radiating from a central point, like starfish arms, and the central point, the mouth, is the phrase “I began the day.”

Calamities has an overarching formal constraint that Jealousy, Last Year at Marienbad, and Nobody Nothing Never don’t have. Sections create the form’s repetition. This makes me wonder about algorithmic or Oulipian-like projects that could be fractal: sets of sections (or paragraphs or lines) that make a fractal pattern.

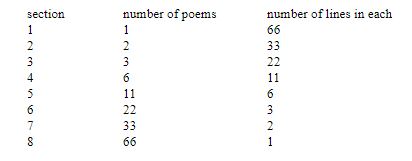

3. Inger Christensen’s it is a possibility (and I know it is a collection of poetry, but I can’t resist). The book is separated into three sections. Anne Carson breaks down some of the math in her introduction to the New Directions copy I have. The first section, PROLOGOS, consists of eight series of poems. Carson creates the following chart:

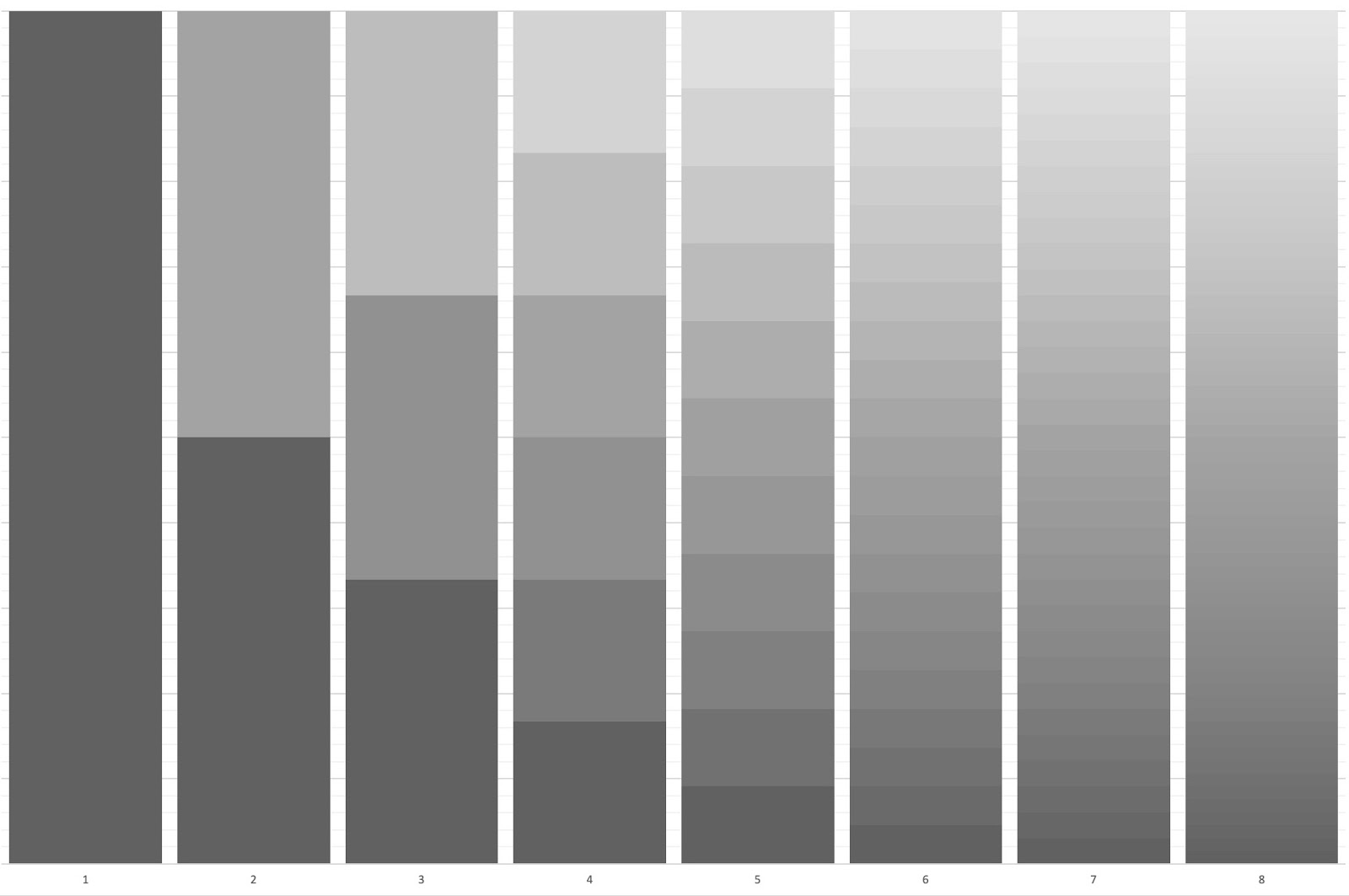

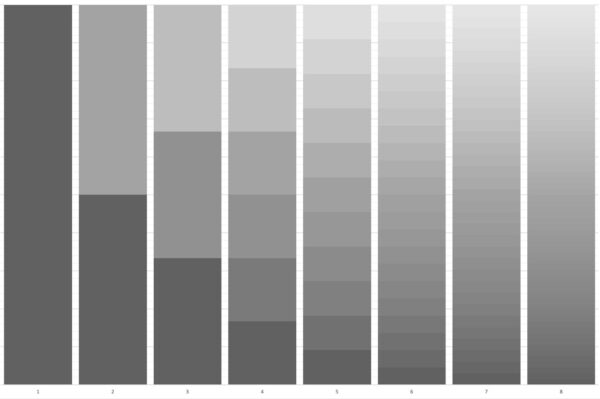

Carson also notes that in the original Danish, each line has sixty-six characters. Each section holds sixty-six lines of sixty-six, and as the sections proceed, the number of lines per poem diminishes until each poem is only one line long. Though no matter how long the poems are, and no matter how many poems there are, each section still contains sixty-six lines total. The grayscale in the chart below shows how many poems there are in each of the eight sections in proportion to the number of lines in each poem. (The rightmost is hardest to see because it holds sixty-six bars, the grayscale fading from one piece to the next, which is appropriate since each of these poems begins with the same word.)

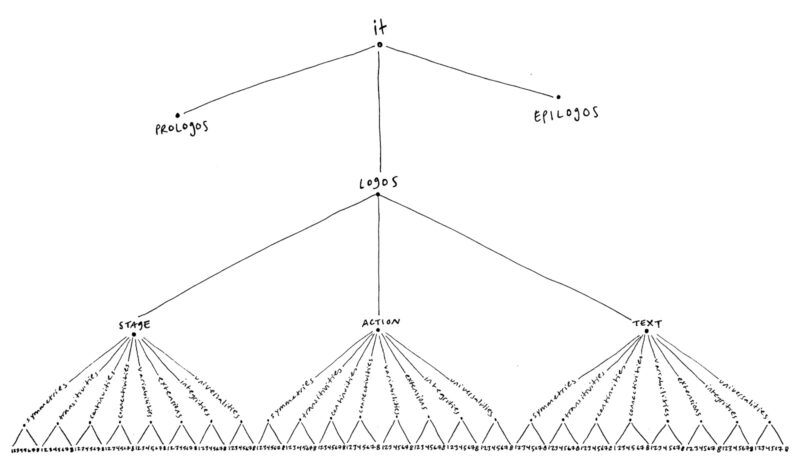

The center main section, after PROLOGOS, is LOGOS, and it contains three sections, STAGE, ACTION, and TEXT, and each of these three sections is made of eight sub-sections of eight poems each. The eight poems are numbered, and the subsections they fall under are titled. These eight titles are the same for each of the three sections of LOGOS. According to Carson, these minor titles are categories of prepositions Christensen found in a linguistics text. Prepositions indicate the position of something, often relative to something else. You can see what’s happening here. I’ll draw it:

The third section, EPILOGOS, is one 527-line (please correct me if I miscounted) poem.

Are either PROLOGOS or LOGOS fractal? Not really, not in the form alone. They are working with scale, sure. They are absolutely fractional. Honestly, I find the overall structure to be the least interesting part. I lay it all out, though, to consider the visualization of a pattern. There is a long history of the role of visualization in mathematics and the sciences, and literature, and I don’t want to get too into it here, but the point is: sometimes abstractions make more sense when you can see them. And patterns, too, especially across texts. That’s what Guerra de la Torre was doing by mapping Stein’s repetitions: she pulled the words out so you can see them, and maybe see Melanctha a little differently.

Regarding the fractalness of it, I might find self-similarity in lines that repeat across the texts or ideas sprung large. Words that appear frequently include structure and function. The numbered poems in LOGOS correspond with one another, shifting position. There is a conversation across levels. What the poems are about is probably most important to puzzle through, fractally, if we’re going to. The premise of it, as Carson also points out, is a generation, a beginning, a let there be light in something, somewhere. The opening of PROLOGOS, in a sixty-six line prose block, illustrates this generation. I’m going to give you a big chunk. This is how the book opens. As you read this, imagine Mandelbrot or Julia sets:

It. That’s it. That started it. It is. Goes on. Moves. Beyond. Becomes. Becomes it and it and it. Goes further than that. Becomes something else. Becomes more. Combines something else with more to keep becoming something else and more. Goes further than that. Becomes something besides something else and more. Something. Something new. Newer still. In the next now, becomes as new as it now can be. Imposes itself. Flaunts itself. Touches, is touched. Catches free material. Grows bigger and bigger. Builds itself up by being more than itself, gains weight, gains speed, gains more in its rush, gains on something else, passes something else, which is taken up, taken in, fast laden with what came first, so randomly begun. That’s it. So changed now that it’s begun. So transformed. Already a difference between it and it, for nothing is what it was. Already time between it and it, here and there, then and now. Already the span of space between it and something else, it and more, it and something, something new, which now, in this now, already has been, in the next now is and goes on. Moves. Fills. Is already enough itself for inside to differ from outside. Plays, shifts, eddies. Outside. And condenses inside. Gains core and substance. Gains surface, refractions, passages, impediments, stimuli among separate parts, free turbulence. Takes a turn, a whole new turn. Turns and twists, is turned and twisted. And pursues an evolution. Seeks a form. Scans its past. Twist after twist takes a different twist. Is picked up to be dealt with again and again. Turn after turn is rephrased. Gains structure in its ceaseless search for structure. Variations inside fed on matter from outside.

“It” is itself and not itself as it grows and folds. Christensen’s sentences fragment and unleash. Are periods creating units that we could separate and count? This doesn’t seem like a thing to count. “It” is forming by twisting and refracting, repeating itself. What “structure” it might “gain” “in its ceaseless search for structure” is the book that follows and its scalar iterations. It’s a kind of infinite text, and shuttered here in my little room, with fresh snow outside, I’m tempted to cut the whole thing apart and tape it to my wall with a net of strings, like I’m solving a crime. The impulse to name and to solve and to identify patterns where there may be none, when the “it” of it is a formless mass, is one I’m struggling with. The Stein article bothers me. I don’t want that work to be bound in a graph. it is graphed in its structure—that’s clear: Christensen has sectioned and numbered. But what is inside feels unnamable.

Stay with me for one more thread.

4. Who or what is “it”? To what does the pronoun refer? The pronominal ambiguity of this project, and these strings of sentences in a shifting non-time, its wild shaped and shapeless form, reminds me of Samuel Beckett’s play Not I and novel The Unnamable. In Beckett’s late novel Company, the “protagonist” (I guess, the primary figure in the novel), experiences a fractured identity via pronouns. The figure hears a voice, but “he” is not sure whose voice it is. The voice addresses a “you” that could very well be “he,” the figure. The voice narrates episodes from the life of “you,” and these episodes are repeated. The voice appears to be an inner monologue narrating the figure’s own memories—the voice separated from the self and narrating as if from above. The “you” is “he.” Later, “he” gains an “I.”

The multiple pronouns the figure inhabits give him “company.” The novel includes many repetitions, in addition to the repetition of self: “Another trait its repetitiousness.” And the repetitions of self in pronouns is, in a sense, hierarchical, or even scaled if we think about pronominal distance, i.e., he → you → I. Though, everyone is a first, second, and third person pronoun simultaneously. What is the edge of a pronoun? Itself?

5. This led me to the novel Pamela by Pamela Lu. A first person narrator is surrounded by friends and acquaintances named only initials (L, R, A, etc.), which causes me to wonder if the narrator’s “I” is like another initial, a name, despite subject-verb agreement telling me otherwise. About halfway through, the narrator writes and rereads recordings of her own experiences and considers a third person, “P,” and later, “Pamela,” which is, of course, the name of the author and the novel itself:

If I was at risk of suddenly becoming P in the midst of a plausible situation, then P was similarly at risk of becoming not me but Pamela, a project that I had invented to include both Pamela and me, and that was expanding, day by day, into a larger persona than either of us could handle. With her endless extemporizing and lack of plot development, Pamela threatened to subsume us in a state of suspended animation, stranding P in the past and me in the present, thereby frustrating all of P’s efforts to catch up with me as well as all my efforts to bring P up to date without losing both our identities… If P was the wallpaper to the house that was Pamela, then I was the resident who paced restlessly through the halls, shutting the storm windows all around and watching the rain happen not to me, but to my house.

6. While reading Lisa Robertson’s The Baudelaire Fractal, I kept thinking of Pamela (Lu’s, not Richardson’s, though there’s another layer). This novel’s narrator, Hazel Brown, wakes up to realize that she’s written the complete works of Charles Baudelaire. She does not become Baudelaire but knows she has written his works. Has some part of her traveled back in time? The novel is a series of sections that share titles with a few Baudelaire poems. Hazel remembers living and traveling in France through her twenties in the 1980s. She remembers apartments and hotel rooms, their similarities, and what books she leaves there:

The Vancouver hotel room I occupied that morning seemed in my state of half-wakefulness to contain all the hotel rooms and temporary rooms I had ever stayed in, not in a simultaneous continuum, nor in chronological sequence, but in flickering, overlapping, and partial surges, much in the way that a dream will dissolve into a new dream yet retain some colour or fragment of the previous dream, which across the pulsing transition both remains the same and plays a new role in an altered story, like a psychic rhyme, or a printed fabric whose complex pattern is built up across successive layers of impression, each autonomously perceptible but also leading the perceiver to cognitively connect the component parts in an inner act of fictive embellishment, so strong is the desire to recognize a narrative among scattered fragments of perception.

Not only are time, place, memory, and a personal history of reading partitioned and conflated, stacked on top of one another, but Hazel’s identity is too. Her name is Hazel Brown, like two eyes. She is a creation of Lisa Robertson. Essays Hazel is writing are essays Robertson has written. The “I” of Baudelaire’s poems, and Baudelaire himself, is in there too: “Form meant my mutable body.”

I was a girl, and my body was time.

I have built various possible worlds—as many as I need.

For the girl is an infraction in thought.

Words that reappear throughout the novel, or ones I underlined, include infinity, fractal, repetition, self-identical, swerve, unfurl, vibration, grace, instant, fold, figure, edge, border, threshold, inner, outer, crystalline, portal, irreal.

I realize I’m just piling up quotations. I’ve been trying to write something about The Baudelaire Fractal since early February. I can’t find what I want to say or a graph to draw.

Hazel writes about / from rooms and the objects in them:

The edges that separate things are conventional rather than inherent or inevitable. While it may make use of these edges in passing, desire is borderless. Once set in motion by a site or an image, swervelike, the line of recollection simply continues, and in multiple directions, intensities, and temporalities, becoming surface, becoming ornament. I feel it in my body as I write this. The scent of a stairway, the glance of a painting and the eyes and the lips and the loneliness nonetheless. Here’s a city that calls—be glorious fully in this poor minute. There is no unidirectional lust. We lean in and it careens to an elsewhere. It’s both ahead of the body and behind the body, as well as all around it, like a voluminous shawl or scarf. Curves, counter-curves, folds entangle. To be held for an instant, to bring the furling velocity back towards the more limited scale of the speaker, desire seeks a language… Images and bodies interlace and resist significance… Meaning is inflected, multiplied, undergoes transformation by means of unchosen frequencies of similarity, projection, sensation, and intense emotion.

If the structure of this work, the math, let’s say—the unknown mechanism in a computer program (the equations in the code), that snaps the flowering lines into place (or not code but the rule in the universe that makes it? is the rule in the universe even real?)—is Baudelaire in Haussmann’s Paris, the arcades with their gridded glass and Benjamin’s writing through them, Benveniste’s mutable pronouns, even Delueze’s folds in Hazel’s many jackets, and Robertson herself, then the novel is like the zoom in a fractal YouTube video: the act of me looking for / at the form, unable to hold even a little bit at a time, because there are no little bits; it’s uncountable. My roving eyes try to put language to what I’m seeing, and then back again to the shapes language makes.

Is The Baudelaire Fractal fractal? Yes? Maybe mid-fractal? Or a part of one? The scale is always changing.

Literally? No, it is not a fractal. None of these examples are. Is a fractal novel possible? Maybe one made by a computer, one with a tighter numerical form. Not a Mandelbrot, not a coastline. The texts I’ve listed, Robertson’s most strongly, are waving at fractal, at mathematics: a language of description, of measurement, like what we do with words, but more crisply?

In Part One of this essay, I wrote that thinking about writing mathematics and writing (about) poetry and prose involves a recognition of the limit of what we can say and how. I think this is actually something Bin said to me about a year ago, and I wrote it down among other notes, and I’m not sure what’s mine or his. But I like the idea of recognizing limits, teasing out the edge of something to find that there isn’t one. Mark wrote me a sentence I’m trying to fold in. The problem I have writing any kind of essay is I never want to make definitive claims—I just keep rearranging. Hazel Brown has many things to say; she’s a composite, multiplied. Thinking of her as fractal is a way to visualize a person—a growing person inside of a book made of books. Thinking of her as fractal is a way to break out of language toward something both measured and immeasurable, to see what we can’t see, and by see I mean understand.

***

In light of our fractured distances, and because I’ve been going around weepily thanking people lately, I’d like to note that both of these essays involved a kind of collaborative effort, not necessarily in writing but via a bower-bird pile of inputs. Friends suggested texts, asked questions, gave encouragement, let me manically text and email them, read drafts, and helped me think through my thinking. Thank you Emily Barton Altman, Stephen Beachy, Marty Cain, Graham Foust (and his winter term class who drew fractals with me), Vincent James, Mark Mayer, Bin Ramke, and Alicia Wright. Josh Agenbroad made the grayscale PROLOGOS graph for it; I drew the LOGOS one.

***

Texts mentioned, though, of course, not a complete bibliography:

Beckett, Samuel. Nohow On: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, Worstward Ho. Grove Press, 1996.

Christensen, Inger. it, translated by Susanna Nied, New Directions, 2006.

Gladman, Renee. Calamities. Wave Books, 2016.

Guerra de la Torre, Juana. “Fractals in Gertrude Stein’s ‘Word-system’: Natural Reality and/or

Verbal Reality.” Atlantis, vol. 12, no. 1/2, 1995, pp. 89-114.

Lu, Pamela. Pamela: A Novel. Atelos, 1998.

Robbe-Grillet, Alain. Jealousy, translated by Richard Howard, Grove Press, 1985.

Robertson, Lisa. The Baudelaire Fractal. Coach House Books, 2020.

Saer, Juan Jose. Nobody Nothing Never, translated by Helen Lane, Serpent’s Tail, 1993.

Stein, Gertrude. “Portraits and Repetition.” Lectures in America. Random House, 1935.

About the Author

Kelly Krumrie‘s prose, poetry, and reviews are forthcoming from or appear in Entropy, La Vague, Black Warrior Review, Full Stop, and elsewhere. She is a PhD candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Denver where she serves as the prose editor for Denver Quarterly.