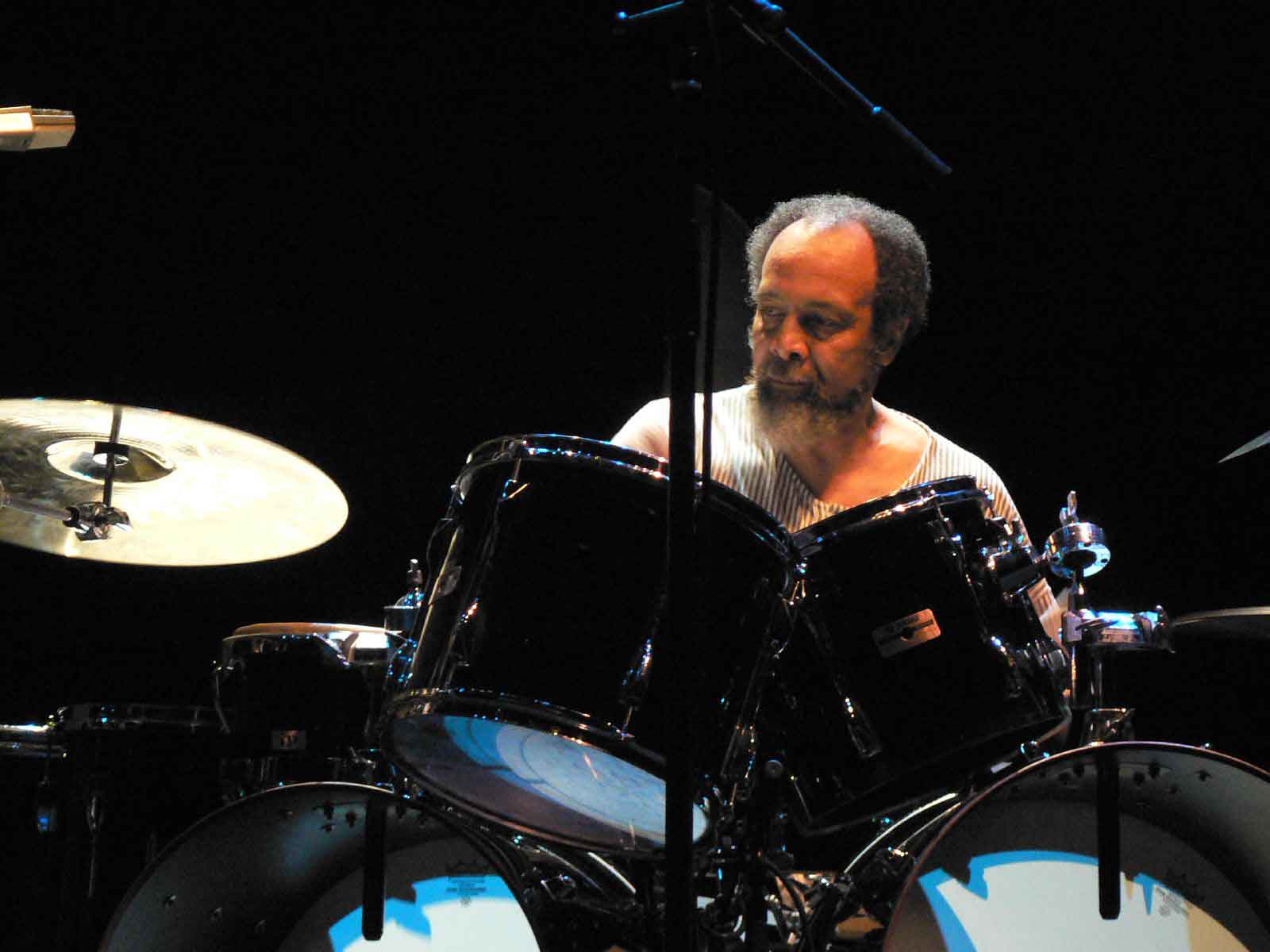

* Professor Milford Graves moved onward & upward to whatever comes next on February 12, 2021, just in time for Lunar New Year. I heard about his illness sometime in summer 2020 & began writing this piece shortly thereafter. I seem to have finished it just as Graves’ corporeal phase has finished. Professor Graves, thank you for a lifetime of inspiration.

In 1994, I took a single fall semester course with Professor Milford Graves at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont. This sparked for me several decades, so far, of research, thought, experimentation, & introspection.

In 2016, Z & I attended a public lecture by Professor Graves, now retired. Notes from that lecture, combined with distant memories and 26 years of rumination, inform the article below.

I have included links at the bottom to relevant books & albums.

7.

Professor Graves has suggested that we liberate drumming from time-keeping.

Sit with that for a moment. Does it feel strange? What do you think drums are for? What do you think they do? (It varies, of course, from situation to situation & from so-called genre to so-called genre.)

Graves is far from the only drummer to work with this idea. Rashied Ali moved in similar directions — often several at once. Elvin Jones (& others before him) loosened the timekeeping requirement. & as we move away from 20th century North America, percussion plays many roles that are not strictly about ‘keeping time’ — all players, of all instruments, may maintain a pulse or awareness together.

It’s worth thinking about the function of percussion — of music — in our lives & in the lives of others both historical & contemporaneous. A Chinese New Year celebration may involve rattles & other small noisy drums, played throughout the house to chase away evil spirits. Tibetan Buddhist music seems to blast the cobwebs from one’s consciousness. In Gnawa & other trance musics, percussion is often repetitive, but it can be difficult for ears raised on rock to identify the pattern: where it starts, where it ends, how it interconnects with the percussive bass patterns of the sintir. The backbeat we know from rock&roll appears to be a variation on/distillation of various African trance rhythms plus some influence from Indigenous American rhythms — all of which has long since become codified & calcified, far from even the supple r&b rhythms of Arthur Crudup’s original ‘That’s All Right’ (simplified, streamlined, & hoe’d down by Elvis & co) or Willie Mae Thornton’s ‘Hound Dog’ (ditto). It’s hard for the listener raised on Presley to hear either recording without a subconsciously superimposed overlay of Elvis’ more overt chord changes & predictable vocal lines, & his elimination of Crudup’s stop-start rhythms — bringing each piece farther away from trance & into a realm more akin to what is commonly known as ‘pop’. The resulting loss of nuance is more-or-less compensated for with hair-shaking ‘wildness’ & chaotic ineptitude — (& don’t get me wrong I love both versions of each song) — performed bombast, as opposed to actual transcendence, one might suspect, tho the effect on Elvis’ Ike-era teenage audience was clearly profound.

Early jazz drumming — especially the bomb-dropping approach to the bass drum — also has a great deal in common with various trance rhythms, tho presented by a single drummer & conjuncted with melodies & chord changes, the effect is of course quite different.

Meanwhile, the constant stream of repetitive ‘pop’, often in the form of background music, to which we are subjected, or subject ourselves, daily, may serve to keep us entranced & passively receptive, in a world awash with advertising & ideology.

Returning to the drums, & to their role in music & our lives:

Professor Graves has suggested getting rid of the cymbals; finding other approaches to the instrument & to time; understanding vibrations. This description calls to my mind The Velvet Underground’s ‘Heroin’ — although as with many ‘rock’-oriented musicians, Maureen Tucker would appear to celebrate lack of knowledge & reliance on some presumed inner compass, while Professor Graves (like at least some of Maureen’s inspirations) is well-read on a wide array of topics, some obviously, others more indirectly, related to music & percussion. His compass may or may not be internal.

Graves’ research includes, among myriad other items, Hermann Helmholtz’ 1863 tome, On The Sensations Of Tone, which you may find translated from the original German. The principles of the Helmholtz Resonator suggest that if you can manage to produce 11.25 beats per second (which is fast), you’re generating a very low A. This may be behind some of both Graves’ & fellow drummer Sunny Murray’s ideas, as described in Val Willmer’s As Serious As Your Life (pp225 & 217 respectively), including Graves’ statement that the saxophone is a drum. In addition, the phrase ‘Of Human Feelings’, known to me as an album title from Ornette Coleman & Prime Time, appears in Helmholtz’s book, which Professor Graves once suggested I read. Taken together with Graves’ & Murray’s comments per Willmer, I find myself guessing that Helmholtz was popular reading among the ‘free jazz’ community. Helmholtz’ principles may also be relevant to what are known today as ‘blast beats’.

Willmer’s book has a LOT to say about Professor Graves & about drums & percussion in general. Indispensable philosophy. I wish I’d had access to it in 1996.

Drums — rhythms — are powerful things. They can keep away evil spirits, or summon helpful ones, or provide a conduit for communication with other worlds. This is why their role in culture has been so heavily reduced (not to underplay the power of the backbeat, which remains omnipresent, but it’s only one approach). If we want to keep humanity moving forward, says Graves, we need to get the drums back. Drums & strings both.

(As the 4/4 backbeat does not qualify as ‘healthy’ in Professor Graves’ estimation, I suspect that distorted chugging electric guitars also do not meet the requirements! Although there are a few collaborations on youtube between Professor Graves & such players as Lou Reed & Marc Ribot. I hold space for optimism that all these elements can be approached in a way that is beneficial or at least benevolent, if approached by the right person in the right way. File under ‘feel’, file under ‘intention’, file under ‘space’, file under ‘magic’ & ‘vibration’.)

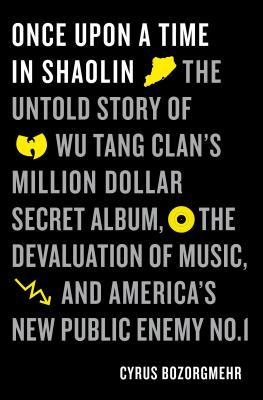

As we all know, reality consists of vibrations. For more on this, see Stephon Alexander’s The Jazz Of Physics or Gary Zukav’s The Dancing Wu Li Masters. A musician, perhaps especially a drummer, is working directly with vibrations — molding the very fabric of reality. Perhaps this is why audience members attending performances by Graves, John or Alice Coltrane, Sun Ra, occasionally report that the music has helped them to recover from a cold or a headache.

“We need to bring art & science together,” Professor Graves suggests. Let them inform each other, let them interact, let them dance. Connect the heart to the brain.

1.

In his early 20s, in the early 1960s, Professor Graves began to study herbal medicine as he explored options for healing the damage done to his system by what remains the standard musician lifestyle. Late nights & weird sleep patterns. Too much alcohol, too much cheap greasy food (often, alcohol & greasy food is part or all of one’s fee). Too many smokes & other abusable substances.

These & their consequent behavior patterns can easily add up to an early death — especially when coupled with the American health care industry, which makes care of any kind available only to the haves (which musicians largely have not). In addition, American health care concentrates on medicines designed for a white, male, straight, gender-conforming individual — leaving the majority of the population out in the mistreated, misdiagnosed cold. Finally, American health care works from an allopathic model, & due primarily to profit motives dating back to Rockefeller, chooses to exclude holistic, homeopathic, & other models which have been of great use in other parts of the world. Traditional Chinese Medicine sees ailments in one part of the body as inherently entwined with the experience of organs which Western health care might never consider as related — sleep apnea, for one example, may derive in part from an abundance of phlegm; this in turn from stagnation in the kidneys; & might be addressed in part by attending to points near one’s low back or knees, or by drinking cider vinegar in warm water, with a spoonful of local honey, each morning. (Check with your local TCM practitioner, or do your own research, before embarking on any plan or cure!)

Potatoes, cabbage, & ‘raw cactus juice’ were among the items Graves added to his diet at that early point in his personal evolution. A few moments of internet research tells me that cabbage is good for ‘clearing heat’, such as that which might be provoked by alcohol consumption or processed foods, while potatoes ‘tonify the chi’ — definitely good for someone seeking energetic balance.

Over time, no doubt, Professor Graves’ dietary needs — or anyone’s — change & evolve. There is no one-size-fits-all diet. You cannot set it & forget it & expect to stay ‘well’.

By the 1990s, Professor Graves had long since become a devoted gardener. Going straight to the source as part of his quest for quality energy, for his or for any human body, he could now eat much of his food directly off the plant, directly from the earth. Witness how stoked the rest of the New York Art Quartet become, in the 2013 film The Breath Courses Through Us, when Graves shows up with potluck.

“Queens is more fertile than most people figure,” Professor Graves told New York Magazine:

“Sometimes you have to eat like an animal,” the Professor said, on his hands and knees. “I tell my students: The energy comes through the roots, the stem. You cut it, you’re truncating power. Sometimes, you have to get down on the ground, open your mouth, and start chomping, hard.”

4.

On and off across the decades, Professor Graves has performed as part of The New York Art Quartet. The NYAQ features Amiri Baraka (lead poet) as well as John Tchicai (saxophone), Roswell Rudd (trombone), & Reggie Workman (bass, originally Lewis Worrell).

Each member of the NYAQ is worth studying in their own right, as is the group’s approach to collective improvisation. For the moment, however…

A professor, a poet, & a playwright, & more, Amiri Baraka was one of only three prominent Black jazz critics in the 1960s, despite it being an especially eventful decade for the music. Besides Baraka, I am thinking here of Stanley Crouch and A. B. Spellman — if I’ve overlooked someone, my sincerest regrets, & please do correct me. Each has their merits & their writing is worthy of study.

Of the three, Amiri Baraka might well be called the most radical, with the most sympathetic ear for ‘the new music’. Baraka was very likely the first to promote & publicize Professor Graves’ music. (See discussion twenty-three minutes into The Breath Courses Through Us.) Some of Baraka’s writing on the music called ‘jazz’, including some discussion of Graves, is collected in Black Music (1966), a book I sip from regularly. Additional thoughts may be found in Baraka’s Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music (2001). His memoir, The Autobiography Of LeRoi Jones (1984), is worth reading as well.

3.

In the 1970s, Professor Graves became captivated by “How the vibration of the drum affects physiological process”. This led Graves to an ongoing close study of heartbeat rhythms: first on vinyl record, then via stethoscope, & eventually via high-tech medical equipment. In the late twenty-teens these studies would be crucial to sustaining Professor Graves’ own life. Given six months to live with a stiffening heart, he applied his studies & experience to influence his own heart’s rhythms, & has kept it beating for an additional two years (so far) beyond doctors’ projected expectations.

Graves told New York Magazine:

“I found this LP, Normal and Abnormal Heart Beats. It was a record for cardiologists. It blew my mind. Everyone says the heart is the drum and the drum is the heart, but here were the secret rhythms, maaaan . . . I started woodshedding the concept.”

Graves has been known to hook musicians up to an EEG, project their heart rhythms on a screen, then direct them to jam along with their own heart’s beats. The advanced tech comes courtesy of a well-deserved Guggenheim award.

…buBUM, buBUM, buBUM…

After a while, Graves began to listen to the sounds between the heart’s bu & its BUM. He amplified those tiny sounds & listened to them closely. They reminded him of bebop. His vocal demonstration of this must be heard to be believed.

The rhythms Graves heard in these subtle rhythms of the heart also possessed some similarities to what he refers to as ‘ritual rhythms’. Given other portions of his 2016 lecture, my guess is that he was referring to rhythms found in Santeria & Vodun.

Professor Graves also spoke about the pitch relationships — the musical intervals — between the various sounds the heart makes. The heartbeat has melodic content! Who knew.

Professor Graves has occasionally performed healing work for those diagnosed with heart arrhythmias, realigning & correcting their heartbeats via percussion. A treatment might include a live performance, &/or a personalized cassette which the patient listens to at home.

After studying countless heartbeats over the decades, Graves identifies the heart as his teacher & his conductor.

Milford imitated a beating heart. He moved stiffly a few times — bu-BUM! — then announced that a heart doesn’t move that way! He oozed himself around his chair a bit while muttering variations on heartbeat rhythms.

That’s how a heart moves. It’s not a metal piston. It’s a part of you. It’s organic tissue. It receives orders from the brain, they coordinate together in each moment to create the heartbeat-motion that is right for the organism at that time. The motion is squishy & organic.

2.

Graves has invented his own martial art, yara, based on the movements of the praying mantis. Local martial arts instructors in NYC (circa 1960s & 70s) refused to teach him due in part to racial & cultural bias. As usual, Graves went straight to the source. See the film Full Mantis (2018) for more about this.

Professor Graves does not lack confidence in the form he has developed. In one interview, he offered to take on ‘Shaq O’Neal’. At the time, Professor Graves was in his early 60s & weighed 180 lbs.

5. — “Pisces have to watch out for their feet!”

I woke up one Wednesday morning in late fall of 1994. Wednesday was the only day I had an early class, & it was half a mile from campus proper, up a hill, off the farthest back stairwell of a haunted mansion which reputedly served as part inspiration for Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting Of Hill House.

The course was a once-a-week three-hour lecture from Professor Milford Graves, & it was absolutely worth it to wake up early & walk up the hill. I sometimes had trouble staying awake through it all, but I figured the info was seeping in anyway. Maybe more effectively, without my conscious mind in the way.

I’d decided at the beginning of term not to take any notes, on the grounds that it was all too much & all too unfamiliar, & I was better off just having the experience. This was possibly not correct, tho it has forced me into intense research in the decades since. Being me, I would still have those class notes today, & probably still be referring to them frequently. I do stumble from time to time on my end-of-term comments from Professor Graves — Bennington doesn’t have grades; you either pass, or you fail, & you receive a comment from each professor — & his comments were in fact prescient. Based on what, I can’t quite imagine.

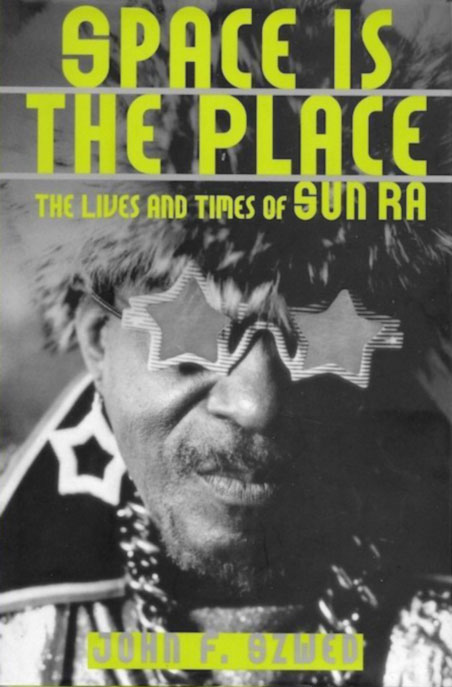

So I can’t tell you with any great certainty what topics were covered in Professor Graves’ course. I know I was expecting more overtly musical content, but I was not ultimately disappointed. I am fairly sure The Egyptian Book Of The Dead was discussed. Sun Ra came up at least once, tho I’d yet to hear of him in any other context — we watched a movie about him one morning & I absolutely could not keep my eyes open for it. If you know me & my tastes & interests at all, you may find this astounding. My guess is that it was too much energetic input. Also, in 1994 it was not yet true of me that (meditation excepted) sitting still for more than a few minutes causes me to fall instantly into a sound sleep.

So I woke up one Wednesday morning in late fall of 1994 & I slammed my foot under the door to my dorm room & I screamed & yelled & swore & hopped around & found some bandage to put on it, & I was late. & I wouldn’t have cared too much, because walking into any class, ever, early or late, is an exercise in mortification, always. But I had a lot of respect for Professor Graves. I was interested in what he had to say. I didn’t want to miss a word. & I didn’t want him to think I thought of his class as inconsequential. It was worth a lot of trouble to me to be there, & for any other class that morning I would likely have stayed home & bled.

Instead, I limped to a friend’s room, a few houses away, knocked on her door & asked to borrow her car. It was a Buick standard shift, old & kind of a boat, & I was the only person allowed to drive it other than her. She gave me the keys, I hopped onward to the parking lot, & my memory insists I walked in at only 17 minutes past — which for a three hour class is not a HUGE amount of late, but Professor Graves tended, as I recall, to start talking straight away & continue til the last moment. I was bound to have missed something.

I made it up the two or three flights of narrow back stairs to Professor Graves’ classroom & as I opened the door, he looked straight at me & announced:

“Pisces! have to watch out for their FEET!”

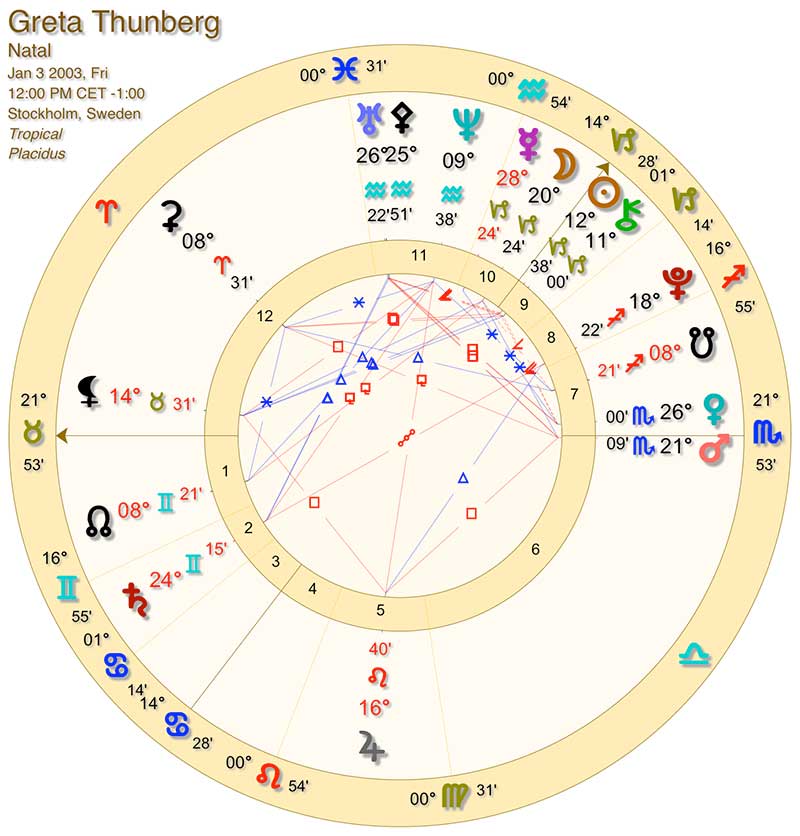

Pisces is the last sign (these days I know these things). Professor Graves had presumably spent the first fifteen minutes of that day’s class going through the other eleven signs & their associations. He might have known my birth date from my school records, so I guess it’s not amazing that he knew I was a Pisces. But there’s NO WAY he knew I’d fucked up my foot. The timing was incredible — his, mine, all of it.

So what’s THAT all about?

(rolls eyes heavenward)

Don’t.

Know.

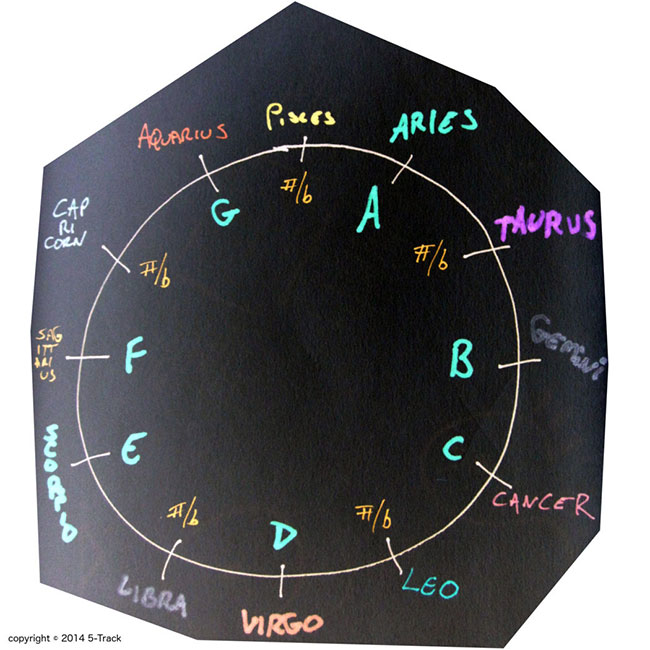

Milford Graves was born on August 20, 1941. His Sun, Moon, Mercury, & Pluto all are in Leo. Venus & Neptune in Virgo, Jupiter & Uranus in Gemini, Saturn in Taurus, Mars in Aries. (That’s Tropical, not Sidereal.) Lots of fire, with just a little air, & a reasonable amount of earth in place to not quite balance things out. Nearly everything on his chart is bundled into the lower circumference, between 8:15 (Aries) & 3 o’clock (Virgo). I was unable to locate Professor Graves’ birth time, so info on his ascendant is unavailable.

Were I to translate his chart into notes, those notes would be:

A A# B C C# D

Symbolically, this chromatic sequence from a root (A) to its 4th (D) is suggestive of a complete motion from one mode of being to another. Not a mere movement, but an entire transformation.

That’s if we take these notes in order of ascending (or descending) pitch. It may make more sense to view them in terms of astrological emphasis.

The greatest emphasis, then, would be on Leo, here expressed as C#, a key notable for its inherent conflict with post-European harmonies & thus with the acoustics of many concert halls. D & B get the next most emphasis, creating a minor motif in B or C#, or the top of a major scale in D. A, A#, & C might best be thought of as passing tones in this chromatic half-octave.

C# B D A A# C

This configuration of notes, lacking obvious implicit harmonies, would lend itself well to a percussive approach, while leaving a great deal of unaddressed harmonic space (the unrepresented half of the chromatic scale, D# through G#). Somehow, this description fits nicely with Graves’ music, his choice of sonic partners & his frequent solo outings, the way his sounds sit nicely under almost anyone, his interest in the busily gurgling between sounds of the heartbeat, & even his approach to vocalization.

9.

Much has occasionally been made of Professor Graves’ decision, when asked, not to join Miles Davis’ soon-to-become-legendary series of electric bands in the early 1970s.

While it sets my muse aflutter to ponder the musical fireworks that might have been, it will be clear to anyone with more than a passing familiarity with Professor Graves’ character, that this pairing at that time did not make any sense. Graves was pursuing a lifestyle based around natural well-being, to the extent that this can be accomplished in Queens. Miles was headed in a direction that, while not unrelated philosophically to Graves’ quest for the source, did nothing to address the ‘musician lifestyle’ issues that had helped set Graves on his path. (Among other conflicts, it has long seemed to me that the corporate touring model is inherently at odds with holistic well-being. There are several obvious ways via which this could be corrected.)

Speaking musically & aesthetically, Miles at this time was moving closer to the backbeat as Graves remained far from it. The only instance I’ve encountered of Graves playing anything like a ‘beat’ — as opposed to ‘rhythms’ — occurs in the film Full Mantis as he seeks to entertain & engage a group of children.

It seems likely that Graves’ role in Miles’ band would have been akin to that later filled by Mtume (&/or Badal Roy on tablas for the In Concert LP from 1972). With Graves in the band, we would most likely have lost Mtume’s drum machine abuse, that gives Dark Magus (1974) such a strange energy. Unless Miles insisted, as he had with keyboardists in the past, that Graves work with electronic percussion. In which case, one supposes, Miles would likely have lost Graves regardless. Who knows, maybe this is part of why the soon-to-be-Professor turned down the gig.

The group would also, most likely, not have sported groove-oriented hand percussion, Graves’ approach to time having long since been liberated — unless the hand percussion kept time while Graves stretched out on kit. But Miles would have gained the rhythmic multi-directionality John Coltrane seems to have been chasing in his attempt to combine Rashied Ali with Elvin Jones. Hints of that feeling show through nonetheless between Dark Magus & Pangaea (1976).

Besides all this, Professor Graves is a big personality. It seems unlikely there would have been room in Miles’ band for both of them. & it was Miles’ band, no question. For some insight into this perspective, see Professor Graves’ conversation with John Tchicai in the NYAQ documentary, The Breath Courses Through Us:

Graves: “Sometimes you can be a bandleader, man, & you can say, I have my music, I want people to play with me. But sometimes you can have four people that can be bandleaders, you know? … I’ll tell you when I have problems playing with other bands… Somebody writes something for me, & deep down inside, I don’t wanna play that. I don’t think I want to be represented like that. … I’d rather for a person say, this is my music, you know, put some drums to it for me. Cos I would never call any one of you guys & say, ‘This is the bass part, this is…’ I wouldn’t do that. Cos I have enough belief in [bassist] Reggie [Workman] to say Reggie, this is what I’d like for the drums, you write the bassline, this is my idea, you know, we gonna talk about personally what we want to do. I would want to have that option to say, beautiful, man, I can deal with that. But also I could say, ‘I don’t feel that line’. That should be open. That’s what stops different musicians from getting together. Because everybody wants to be the bandleader.”

Graves had a family to support. He could certainly have used the paycheck. But rather than join Miles Davis, & despite having no degree, Graves chose to work instead in human & veterinary medical technology, learning the technical skills that would one day serve his own research & prolong his own life.

In 1973, trumpeter Bill Dixon offered Graves a teaching position at Bennington College, a tiny arts college in the woods of southwestern Vermont. Graves required some convincing, but eventually accepted the steady income. Professor Graves continued to teach at Bennington college, commuting from his home in Queens, until 2012.

Bill Dixon joined the ancestors in 2010. He is best known for his work with Cecil Taylor & for spearheading the October Revolution In Jazz (1964), a four-day music festival focused on a single venue in Manhattan, which spotlit the avant-garde while helping to introduce the new music to a larger cultural stage. Dixon has made a number of fascinating recordings, under his own name & with various groups. Several are available on bandcamp:

https://billdixon.bandcamp.com/

https://lascarferu.bandcamp.com/album/modus-operandi

https://aumfidelity.bandcamp.com/album/17-musicians-in-search-of-a-sound-darfur

https://destination-out.bandcamp.com/album/berlin-abbozzi

6.

Professor Graves was a student & practitioner of acupuncture, which in turn is an aspect of Traditional Chinese Medicine (aka TCM). An ailment in the liver might be connected by meridian to a trigger point located elsewhere on the body. An acupuncture needle stuck correctly into that point, for a correct amount of time, will aid the liver. (Do not try this at home without training. Acupressure, however, is peachy-keen to fool around with & you should waste zero moments in doing so. I am told that arnica gel is a great way to stimulate the points, being more energetically conductive than the material used in acupuncture needles. I have worked with arnica gel in this context & found it to be effective.)

Graves spoke to us in 2016 about ‘electronic stimulation of muscles’. Using a TENS unit, he can stimulate an entire muscle. Acupuncture needles, however, are required if he wants to get specific. To display the kinds of movements he could stimulate with electricity, Graves flipped his arm around rhythmically.

“If you think you can’t dance,” he told us, “I can make you dance!”

Through this use of acupuncture needles, Professor Graves went on to say, he could simulate possession, such as that found in Vodun or Santeria. It seems to me that, by way of entrainment & intention, one might not just simulate, but stimulate possession. (For that matter, it is possible that I misheard.)

Graves spoke further of affecting the heart’s rhythms by stimulating the amygdala or other parts of the brain. About listening to, or otherwise measuring, the heart’s rhythms via points on the head. Studying the heart by listening to the brain! Since the heart’s movements originate with the brain, & since the two are always in vibrant & ever-changing dialogue, this is in some ways a more direct approach.

8.

Near the end of the year 2016, shortly after we saw him speak, Professor Graves performed an improvised duet in Bologna, Italy, in which his duet partner/s were ‘adult human stem cells’. Graves made sounds, the cells responded, & Graves responded to the cells’ response — just like any improvised duet. The cells’ contributions were transmitted to a large screen via microscope equipped with ‘hyper spectral imaging system’.

How did this come about?

In 2005 the New York Times conducted an interview with Professor Graves, about his work with musical healing & heartbeat rhythms. Once the article was published, people around the world began reaching out to Professor Graves, wanting him to cure their various heart ailments. But Graves is not a doctor. The attention was not entirely welcome.

Other calls came in. A microbiologist. His aim, to help the human body develop its own stem cells. He’d been inundating the cells with extremely high frequency tones, in hopes of stimulating growth.

It wasn’t working.

Milford was not at all surprised, because the sounds weren’t organic. Think of the beeping of your microwave, your smoke alarm, a big truck backing up outside — do these things help your body grow? or do they injure you in some small way? Graves thought of his own early experiments, the squeals of feedback he’d blasted his students with, unintentionally, back in the 1970s. He sent the microbiologist a recording of some ‘heart music’. That got the stem cells going.

The scientists were amazed. They wanted to know where Graves got his ideas.

Professor Graves has mentioned, in conjunction with heart sounds & rhythms, such things as chakras, spirit possession, kundalini yoga. He expresses his desire to “use everything in human culture,” his wish that ‘science’ would do the same.

Science, he says, won’t listen to anyone without a PhD.

In addition, science tends to discount much of human history. Most anything coming out of Africa, in particular, has long been disregarded. Beyond a mistreatment based on skin color, this represents a long-term bias against an entire continent as a worthwhile source of information. This bias has at least partial roots in the desire of Europeans to reduce that continent — which, when they encountered it, already boasted vast civilizations — to a source of profit for themselves.

Projected on the wall behind Professor Graves, during his 2016 talk at Bennington College, was an image labeled ‘Ashanti-Adinkra Cloth Symbols’. Spirals & wavy lines & so forth, with labels under them along the lines of ‘strength’, ‘joy’, etc. They reminded me of various types of runes, from the Mayans to the Celts to the reiki symbols.

Graves told us that the ‘cloth symbols’ resemble the trails left by subatomic particles. He traces them on his drum heads as he plays (perhaps among other applications). I presume this is a way of evoking the energy, or associated spirits, of a given symbol.

When I asked how he thought I might try this on guitar, he explained that he originally got the idea from stringed instruments, & suggested I read On The Sensations of Tone by Hermann Helmholtz. I did that, & it was fascinating, & I still don’t see the connection.

Nonetheless I have tried applying the concept using Celtic runes (Futhark), reiki symbols, & elements of the I Ching. I have worked with this technique on guitars & on drums. I have found ways to ‘draw’ symbols on the fretboard, via fingerings, & I have pictured various symbols in my head while playing, be it improvised music or otherwise. Well worth the experiment, especially if you already dabble in energy work or magic.

Scientists, Graves says, always want to know where his ideas come from. He rolls his eyes upwards & intones:

“Don’t. Know.”

Not being religious, he says, he can’t say they come from God. But he does think of himself as spiritual. Maybe they come from the five most powerful spirits of Santeria — who, like the loa of Vodun, have their roots in African spirituality — but he can’t say that to a scientist either. When a scientist suggested it was ‘intuition’, Milford went along with that.

Why not?

10.

“Do what you do. Enjoy what others do. Only you do what you do.” ~ MG

Here are two other morsels from the talk I attended in 2016, followed by links for you to rabbit hole with:

• A story about an interview Professor Graves gave in Japan, speaking with the publisher of a magazine plus an audience of twenty or so. About an hour in, the publisher left to consult the ancestors & change from his suit & tie to traditional robes. Then he came back. After that, says the Professor, “It got deep like Santeria”.

• Professor Graves’ theory of how UFOs make sudden 90-degree turns through abrupt internal movements in various directions, perhaps through various dimensions. The explanation involved motion based on martial arts & African dance, & reminded me of stunt drivers I’ve observed working out on the freeways in & around Los Angeles.

lynx —

Professor Graves official website: https://www.milfordgraves.com/

• Full Mantis — https://www.fullmantis.com/

• The Breath Courses Through Us — https://vimeo.com/59617230 … around 58:00 Graves discusses his work with heart rhythms & herbs, & healing work in general. There’s also a great conversation around 50:00 between Graves & John Tchicai, discussing composition as it can relate to freedom.

• Cell Melodies — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEUQqcoXGYE

Graves’ first album, Percussion Ensemble (1965) for ESP-Disk, is available on bandcamp. This record consists of a series of duets between Graves and Sunny Morgan: https://milfordgraves.bandcamp.com/

Two more albums appeared in 1977 — Bäbi & Meditation Among Us — these can be difficult to locate, tho both are excellent should you stumble across them. The internet is your friend.

Graves’ excellent recording with Anthony Braxton & William Parker, Beyond Quantum (2008), is available from Tzadik Records, along with his astonishing solo CD Grand Unification (1998); an epic duet with label-owner John Zorn (50th Birthday Celebration Volume Two, 2004); & another solo CD, Stories (2007). Graves has been known to attach drumsticks to his knees, elbows, & head, in addition to those two or more which are held, as usual, in his hands. https://www.tzadik.com/

Also very much worth your time:

https://billlaswell.bandcamp.com/album/the-stone-april-22-2014 This one’s a duet for electric bass & percussion, an unusual standout in Grave’s unusual discography. Primarily meditative. A couch-lock soundtrack for the ages.

https://giuseppilogan.bandcamp.com/album/the-giuseppi-logan-quartet This recording from 1964 catches Graves quite early in his conceptual development, not terribly long after his switch from playing primarily Latin music & hand percussion, to a version of a drum kit & something that might better be described as ‘jazz’. Also featuring Don Pullen on piano, otherwise heard with Graves in a duo format on two excellent live albums from 1967.

https://paulbley.bandcamp.com/album/barrage A release from early 1965, this is especially notable for the presence of Sun Ra mainstay Marshall Allen. If you’re a fan of the sound & feel of early New York ‘free jazz’, this album will make you happy. So often that feeling is lost behind the powerful personalities of John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman — the same can happen with rock&roll, where we notice Mick or Lou but fail to clock the sublime prowess of the band. With this set of performances you can almost smell the air in the room, or outside the window.

https://lowelldavidson.bandcamp.com/ As with the Paul Bley release, above, I’d never heard this music before tonight, but it’s lovely. Recorded in 1965, around the time of Graves’ first solo recording. Bassist Gary Peacock rounds out this gorgeous trio.

Professor Graves also appears on Albert Ayler’s Love Cry (1968). Love Cry is a strange & perhaps transitional album which finds Ayler experimenting for the first time with shorter pieces & electric instruments — in this case a keyboard of some sort. My own feeling is that this music could have been recorded better, perhaps by someone with an understanding of rock instrumentation & related microphone &/or mixing techniques. Then again, the same could be said of The Velvet Underground’s first two albums. Technology & experience, in 1968, just had not caught up. But the performances on Love Cry are fantastic, among my favorite of Ayler’s or Graves’ recorded works.

A live Albert Ayler recording featuring Milford Graves on drums may be found on Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962–70), released on John Fahey’s Revenant Records in October of 2004. Sadly, this collection is out of print. It includes a recording of Ayler’s band, which included Graves, ‘performing’ (if that is the correct word — ‘emanating’ or ‘channeling’ might be better) at John Coltrane’s funeral. This powerful distinction is shared only by Ornette Coleman’s group.

You will also want to check out Graves’ duets with pianist Don Pullen. My dear cat-friend ~Kira~ might describe Pullen’s music as “something like Cecil Taylor, but friendlier.”

‘Energy music’ often seems to be about The. Most. Intense. Energies. But this duo’s music is playful, even gentle at times. Think of The Sun, of children playing in the daylight. (Tho album title Nommo (1967) might suggest we consider The Star instead.)

I don’t see a bandcamp link so dig around youtube & you’ll find some things.

Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman (1970) also features Graves on drums. A rare chance to hear Graves accompany electric guitar. Sharrock at this time was still early in his journey — for a sense of where he ended up, check out his Ask The Ages (1992), which features Elvin Jones on drums: https://billlaswell.bandcamp.com/album/ask-the-ages

I would be deeply remiss if I did not mention again the work of the New York Art Quartet, the group featuring Graves alongside poet Amiri Baraka, John Tchicai (saxophone), Roswell Rudd (trombone), & Reggie Workman (bass, originally Lewis Worrell).

Their 1965 LP for ESP-Disk is available here:

https://newyorkartquartet.bandcamp.com/

Other NYAQ titles include Mohawk (1965), 35th Reunion (2000), & various archival releases.

In addition to all this, I have mentioned several books which you may wish to check out:

Amiri Baraka — Black Music

Amiri Baraka — Digging: The Afro-American Soul Of American Classical Music

Amiri Baraka — The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones

Val Willmer — As Serious As Your Life

Hermann Helmholtz — On The Sensations Of Tone

read here — https://archive.org/details/onsensationsofto00helmrich

purchase there — https://bookshop.org/a/2778/9780486607535

Stephon Alexander — The Jazz Of Physics

Gary Zukav — The Dancing Wu Li Masters

Shirley Jackson — The Haunting Of Hill House

I have been unable to identify the Normal & Abnormal Heart Sounds LP which Professor Graves studied in the 1970s. However, a quick search on youtube should turn up a few examples. Or you could pick up a stethoscope, as Graves did, & start listening to your own pulse & that of your friends (with their consent of course).

I am obligated to mention that links to Ecstatic Attic via bookshop.org will provide Z & me with a very small measure of profit (roughly $65 last year, whoo!). Whether you go through Ecstatic Attic or otherwise, I would strongly suggest you use https://bookshop.org/ whenever possible, as in doing so you help support independent bookstores everywhere.

About the Author

5-Track is a fractal nexus.

About the Author

5-Track is a fractal nexus.