Kelly Krumrie’s figuring

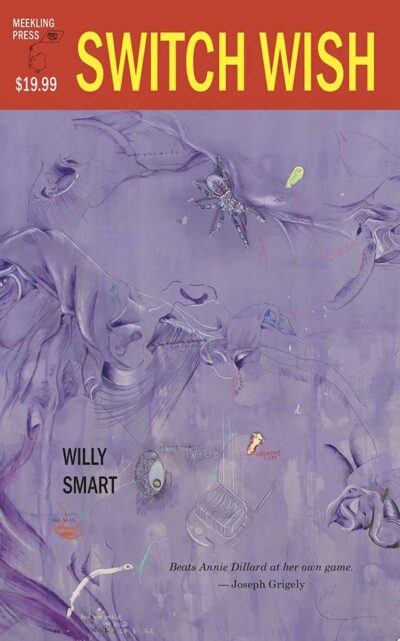

Review of Willy Smart’s Switch Wish

Figuring is a monthly column that puzzles over (to figure) and gives shape to (a figure) writing, art, and environments that integrate or concern mathematics and the sciences. This month’s column reviews Meekling Press author Willy Smart’s novel, Switch Wish.

Kelly Krumrie’s figuring

Review of Willy Smart’s Switch Wish

Figuring is a monthly column that puzzles over (to figure) and gives shape to (a figure) writing, art, and environments that integrate or concern mathematics and the sciences.

I’ve been excited about a lot of books lately, but few have made me annotate, text photos of pages to folks, flip back and forth, make little ooo ahhh sounds as much as Willy Smart’s Switch Wish. In setting out to write about it, my impulse is to read the book again, and again—the first time, I read it one sitting. Though the novel is 135 pages, the object itself is small, and the font is large, so it’s not quite as long as it seems. I am reminded of Emily Dickinson’s wondering

Did you ever read one of her Poems backward, because the plunge from the front overturned you? I sometimes (often have, many times) have – A something overtakes the Mind

—my temptation suggesting I now read the book backwards, which I could do, probably, without too much trouble. Such is the nature of this “erotic novel in disguise.” Reading Switch Wish, I am overturned.

Both eroticism and the novel form are “in disguise” here: the erotics are between a narrator and the natural world; the narrative is this interplay: the drama between lover and beloved, but the beloved is a pond, cut flowers, an algae-covered stone. The reader follows the narrator experiencing the natural world and thinking about it: the novel includes facts and references, objective observations of outdoor environments. The narrator muses on theater, film, music, literature. In this way, we are following a mind as it creates and works through fantasies.

The erotics are of the body as well as the mind, tuned into hands, lips, thighs, tongue. And seduction, the other’s pull and the pull to want to know the unknowable other:

The water looks blurred, it’s not. It really is that smooth, but not for me. Glossy water looks blurred, which means that its details have been relaxed. When I touch the water, its softness pulls away in a little swell. A ripple. The water truly is glossy in my looking, but as well is not glossy in my touching. What it is slips on my approach. Getting up against the water’s surface with my hand doesn’t mean I’m getting closer to how it is right there against my forefinger’s tip. A blurred image makes a haptic demand. Or rather, it doesn’t make a demand but impels a compulsion. That’s why I’ve touched it. Now the water’s gloss settles itself across the water’s surface again.

Swell, glossy in my looking, slips on my approach, getting up against, forefinger’s tip, compulsion—an erotics of dipping one’s finger into pond water. The experiment and observation are at once scientific and enticing. The language is clean and somewhat formal; still I’m unsettled—back to Dickinson: “a plunge… overtakes the mind.”

The images above echo across the text: glossy lips and makeup, mirrors, dewy spiderwebs, sweaty armpits, glass, spit, algae. Repetition is a way of getting to know: to reach again and again. Anne Carson writes about this in Eros the Bittersweet. The lover reaches for the beloved but can never catch them for desire is in the reaching: “That which is known, attained, possessed, cannot be an object of desire.” Nature is unpossessable like that.

Smart’s narrator knows this is how desire works:

A fantasy, though, does not end. Its material is not the done but the doing: not the finished model airplane but the plan for its construction. I don’t want the airplane, I want the instructions. I don’t want to do my fantasies, but I want to plan them.

The novel, in the spirit of fantasy, is mostly made of the narrator’s thinking. What Smart does best here is balance the intellectual with the physical, even though the narrator’s body is somewhat invisible: we only see them through their eyes: their application of chapstick, the smell of their own sweat—never through another character. In fact, other humans appear only in memory or in summaries of movie scenes. This is quite a feat—a shearing off of typical ways we know character—and one I’m thrilled to see.

One example of the intellectual / physical balance working exceptionally well is a moment where the narrator uses their body to attempt to measure the circumference of the pond they frequent. They lie in the mud and mark their length head to toe, then move to the next position, mark, move, and then count. It’s muddy, and their t-shirt gets wet and clingy. Then they switch to measuring the circumference with their thumb, a much smaller unit. This is an enactment of the coastline paradox, a type of fractal problem where using a smaller instrument lengthens the distance[1]. Here, the distance around the pond is greater if the narrator uses their thumb. For the record, I have written similar scenes; I am obsessed with the history and idea of body parts as units of measurement: how imprecise, how messy, how always in flux the body is… A muddy, wet t-shirt would mess up a measure. And in this scene the narrator is alone—is a wet t-shirt sexy if there’s no one else to see it?

What are the results of Switch Wish’s measurements? Much is measured here, but measurement is also thwarted, and this tension loops across the text. This is a novel of observing and reaching. The narrator’s desire is erotic and intellectual. When a scene or idea is repeated or looped, it still delights and surprises because desire—like the incomprehensible movement of the water striders the narrator spies over and over—is a “mechanism [we] can’t witness”—not exactly, and never only once.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] I mentioned this briefly in On Fractals, Part 2—and I could add Switch Wish to this list of fractal texts, certainly. There is also a beautiful moment in the novel about sweaty palms and the imaginary of mathematical proofs which I get at a bit here. But I don’t want to send you astray or ramble on and spoil too many of the novel’s secrets before you read it.

About the Author

Kelly Krumrie‘s prose, poetry, and reviews are forthcoming from or appear in Entropy, La Vague, Black Warrior Review, Full Stop, and elsewhere. She is a PhD candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Denver where she serves as the prose editor for Denver Quarterly.